Fall 2024

José Francisco Xavier de Salazar Y Mendoza

The portrait artist who immortalized the faces of Spanish colonial Louisiana

Published: September 1, 2024

Last Updated: December 1, 2024

Louisiana State Museum

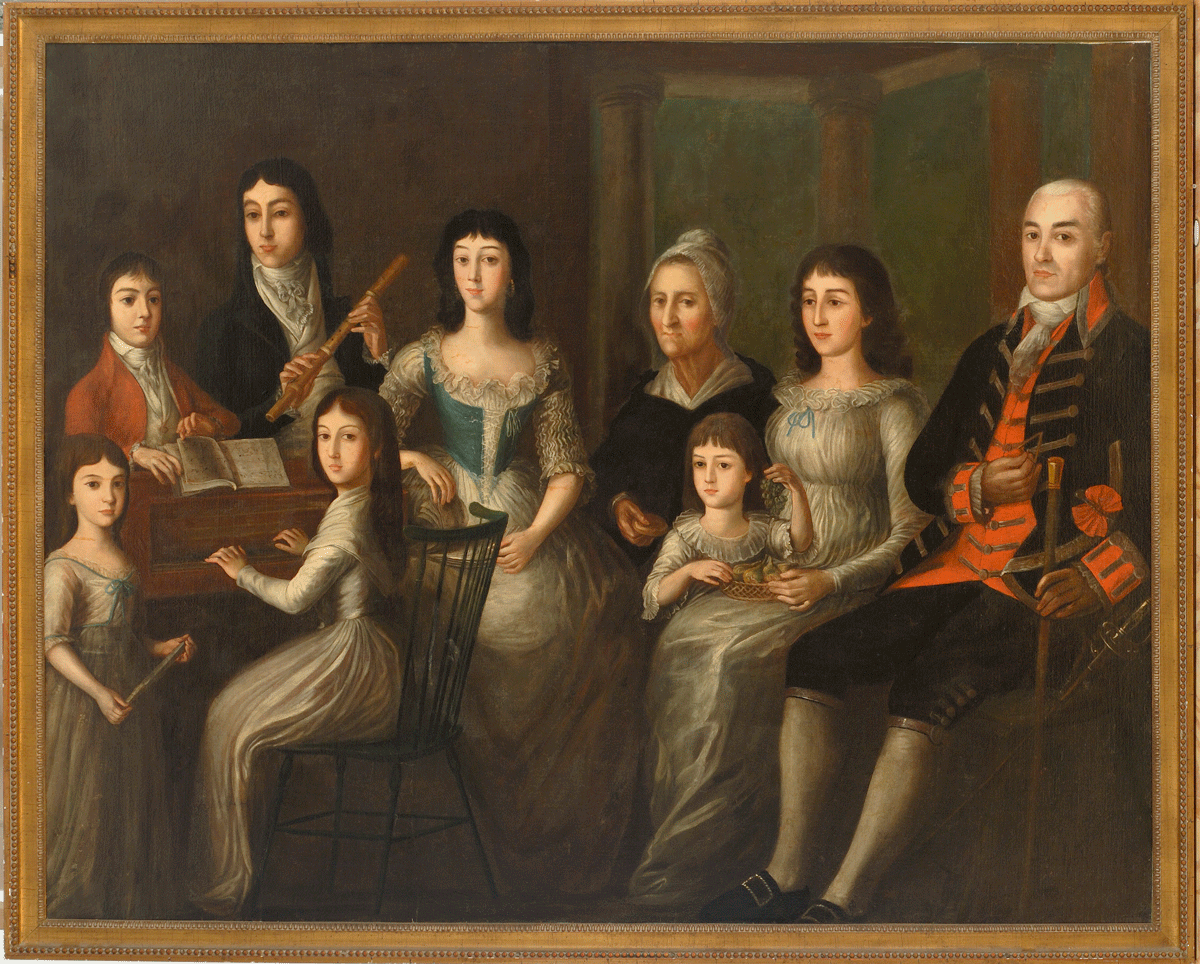

Jose Francisco Xavier de Salazar y Mendoza , portrait of the family of Dr. Joseph Montegut, 1798–1800.

José Francisco Xavier de Salazar y Mendoza, active between circa 1750 and 1802, was the first identifiable and most preeminent portrait painter working in Louisiana during the Spanish colonial period. Appreciation of his work has not waned over the last two centuries, and today Salazar’s portraits remain highly prized by museums, institutions, collectors, and descendants of the sitters. Salazar’s paintings have been featured in numerous exhibitions on early American portraiture and in solo retrospectives at the Louisiana State Museum and Ogden Museum of Southern Art, and have achieved record-breaking prices for Louisiana portraiture at auction.

By 1784 Salazar, his wife María Antonia Magaña, and their children José and Francisca voyaged across the Gulf of Mexico from Mexico’s Yucatán Peninsula to New Orleans. The Salazar family’s arrival coincided with Spain’s four-decades governance over Louisiana dating from 1763 to 1803. Already an accomplished portrait painter, and accustomed with the Spanish language and culture, Salazar and his family assimilated into life in colonial New Orleans; he would earn prestigious portrait commissions from political, community, military, and religious leaders, as well as prominent families, during the Spanish colonial period.

Jose Francisco Xavier de Salazar y Mendoza, portrait of Captain Julien Vienne and son Julien George Vienne. The Historic New Orleans Collection

On Good Friday morning, March 21, 1788, disaster struck and fire engulfed the French Quarter, burning to the ground over 850 buildings, including residences, the parish church and Presbytère, casa principal, military barracks, and public jail. Without an organized fire department, the fire raged uncontrollably and left hundreds of families homeless. The Salazar family was among the homeless and many, including the Salazars, built makeshift tents and cabins in the Presbytère garden with aid provided by Governor Esteban Miró and Father Antonio de Sedella, known as Père Antoine, the beloved pastor of the Church of St. Louis. The Salazar family was able to recover from the fire and, in the 1791 census, listed their new residence on St. Philip Street.

Little is known of Salazar’s art training, and so far, none of his Mexican paintings have been identified. Evidently, Salazar was largely a self-taught artist. The religious artwork and décor of the elaborated interior of the Cathedral of San Ildefonso in Mérida, Mexico, where numerous relatives of both Salazar and his wife were baptized and married, may have given inspiration for Salazar’s artistic career. It is also possible that Salazar had become acquainted with the extensive art collection of Archbishop Antonio Caballero, who became Bishop of Mérida in 1775.

Portraiture representing the culture, sophistication, and wealth of the sitter predominated at the time in both America and Europe. Drawing on sixteenth- and seventeenth-century-European and Spanish Baroque portrait traditions, Salazar employed distinctive devices and techniques that make his work recognizable. Upright posture in the sitters, along with soft modeling and delicate treatment of lace and fabric, were characteristic of his portraits. Often Salazar painted a child or young woman with a flower or fruit in their hand, reflecting their youth and innocence. The late-nineteenth-century-Louisiana-portrait- and landscape-artist George David Coulon was the first to chronicle the history of local artists, at the request of fellow artist Bror Anders Wikström. Coulon’s ephemera and reminiscences, written when he was seventy-nine, were compiled into what is known as Scrapbook 100, part of the Louisiana State Museum’s Louisiana Historical Center. Coulon was well conversant with Salazar’s portraiture and wrote critically, “He made good ‘likenesses,’ but he was not much of a colorist.”

Salazar frequently favored an oval format within a rectangle canvas, as in the portraits of father and daughter Lieutenant Michel Dragon and Marianne Celeste Dragon now in the Louisiana State Museum’s collection. Of Greek descent, Dragon served in the Spanish colonial military and chose to wear his uniform for his portrait, alluding to his rank and place in society. Marianne’s portrait has her seated by a table with a basket of fresh flowers, with more flowers on the bodice of her dress and in her hand, representing her femininity and youth. Dragon’s wife, Marianne Francoise Chauvin de Beaulieu de Monplaisir, was of a mixed Canadian-French heritage that included American Indian and African descent; Salazar’s portrait of daughter Marianne Celeste Dragon reflected her mixed-race heritage and that she would have been identified as a free woman of color at the time.

Jose Francisco Xavier de Salazar y Mendoza, portrait of Madame Célèste Antonia de Lavillebeuvre.

Salazar’s portraits incorporate personal references and preferences of the sitter, as illustrated by the affectionate relationship depicted between a father and his young son in Captain Julien Vienne and Son Julien George Vienne. A successful merchant, Captain Vienne served in Bernardo de Gálvez’s military campaign against the British. It was rare that a father chose to have his child painted in his portrait, an option usually reserved for a mother and child or group family portraits. Instead, Captain Vienne was presented in his full uniform, wearing his hat, with one hand on his hip and his other wrapped lovingly around his child.

The portrait of Madame Célèste Antonia Lavillebuevre shows the sitter with a fashionable bouffant hair style and an elegant dress, posed at a piano with sheet music in her hand. Set within the interior of her home, her portrait reflects her sophistication, musical talents, and education.

The group portrait of the family of Dr. Joseph Montegut encompasses a multi-generational family, with the five older children gathered around a piano; two of the children have flutes in their hands, and the youngest child stands close beside her mother. A French-born and -trained doctor, Joseph Montegut served as surgeon major in the Spanish colonial army and later as chief surgeon at Charity Hospital. A veteran of the Battle of New Orleans, Dr. Montegut holds a triangle in his hand, likely a Masonic or fraternal symbol. Originally the group portrait was likely two pendant portraits that were merged at some point, and the portrait of Madame de Marigny, the elderly aunt of Dr. Montegut’s wife Madame Françoise Montegut, was added, possibly by another artist.

Among Salazar’s most prestigious portrait commissions were the full-length larger-than-life-sized portraits of Don Andrés Almonester y Roxas and Luis Ignacio Maria Peñalver y Cárdenas, Bishop of the Diocese of Louisiana and Florida, replete with cartouche shields referencing the sitter, artist, and date. Almonester in his civic capacity and Cárdenas as religious leader played noteworthy roles during the Spanish colonial period. These portrait commissions solidified Salazar’s position as the most important portrait painter working in late-eighteenth-century Louisiana. Other portrait painters, including Joseph Furcoty and Joseph Herrara, have been identified as artists working during the Spanish colonial period, but none have earned the recognition and reputation achieved by Salazar.

Since opportunities to study art were limited for women at the time, Salazar’s daughter Francisca pursued her artistic career under the tutelage of her father and assisted him with his portraits. After Salazar’s death, Francisca was commissioned to paint a copy of her father’s portrait of Bishop Luis Ignacio Maria Peñalver y Cárdenas, intended for display in the St. Louis Cathedral. The portrait, which was the only signed work by Francisca, was regrettably destroyed in the Cabildo fire of 1988.

After an illustrious career as the premier portrait painter of the Louisiana Spanish colonial period, Salazar died in 1802. He was fifty-two years old. Less than two years after Salazar’s death, Spain would relinquish Louisiana to France. But the Spanish colonial period in New Orleans left a lasting impression, made possible in part by Salazar’s visual account through his legacy of portraiture.

Claudia Kheel is a southern regional art specialist.