Spanish Colonial Louisiana

Spain governed the colony of Louisiana for nearly four decades, from 1763 through March 1803, returning it to France for a few months until the Louisiana Purchase conveyed it to the United States in 1803.

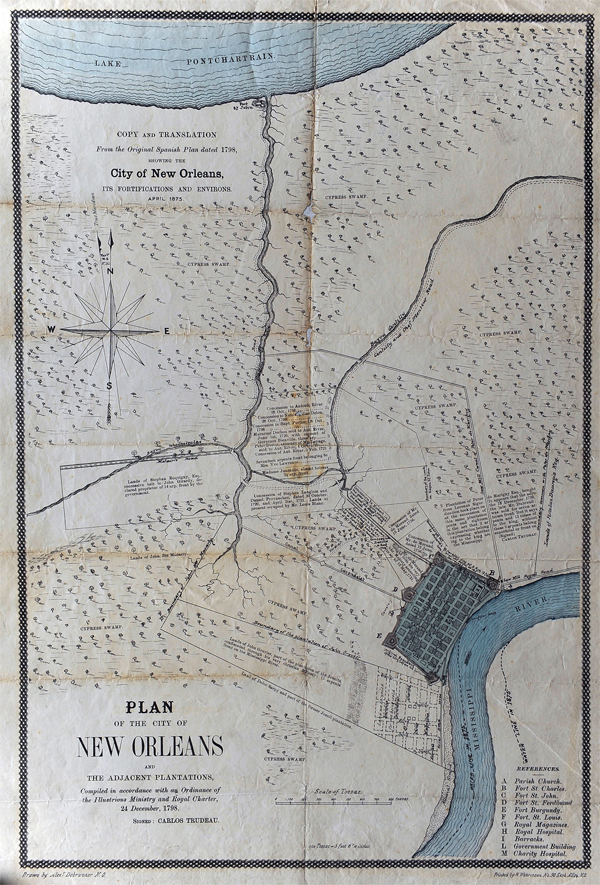

Courtesy of The Historic New Orleans Collection.

This translated copy shows the original Spanish Plan of New Orleans from 1798.

Spain governed the colony of Louisiana for nearly four decades, from 1763 through March 1803, returning it to France for a few months until the Louisiana Purchase conveyed it to the United States in 1803. Under Kings Carlos III and Carlos IV, the administration of Spain’s Atlantic empire was strengthened and improved through a number of policies called the Bourbon Reforms. In Louisiana the period began amid uncertainty and a major rebellion, but it ended with an unprecedented degree of prosperity. By disbursing large annual subsidies and employing competent administrators who were culturally sensitive to the colony’s French-speaking Creole population, the Spanish managed to accomplish what their French predecessors had never done—make Louisiana a relatively stable, growing outpost, even as the turbulent age of Atlantic revolutions unfolded.

The period was also marked by the dramatic expansion of slavery in the young colony. The unprecedented arrival of thousands of enslaved Africans, combined with Spain’s liberal manumission policies, contributed to the growth of a caste of free people of color. Many of them lived in New Orleans, which developed significantly during the Spanish period and was largely rebuilt in the wake of catastrophic fires in 1788 and 1794. Driving these demographic changes was the lower Mississippi Valley’s plantation economy, which accelerated in the mid-1790s as cotton and sugar replaced tobacco and indigo as the region’s major cash crops. Trade and credit connections multiplied—both upriver toward the expanding American West and downriver toward the Gulf—as New Orleans grew into a vital port integrated into the Atlantic economy. By the time Louisiana was sold (over Spanish objections) to the United States, it had been transformed from a sparsely settled military buffer zone into a dynamic commercial center.

1762–1769: Cession, Uncertainty, and Rebellion

The colony’s economic potential was, ironically, only a secondary consideration for Spanish officials when they initially gained possession of Louisiana through a peace treaty. During the French and Indian War (1756–1763), King Carlos III of Spain supported his Bourbon cousin, Louis XV of France, only to lose important colonies in Cuba and the Floridas to the victorious British. Likewise, the French had lost their northern colony of Canada to Great Britain, so as partial compensation to Spain for its losses, France ceded the rest of its North American territory—Louisiana—to Spain with the 1762 Treaty of Fontainebleau, which was kept secret until France could negotiate peace with the British. The French preferred Louisiana to be under Spanish control than in the hands of Great Britain.

In 1763 France, Spain, and Great Britain signed the Treaty of Paris, ending the French and Indian War. For the Spanish, Louisiana would now serve as a generously subsidized military colony, keeping lucrative Mexican mines safe from the ambitions of British North America, which now extended as far west as the Mississippi River.

When Spain inherited Louisiana, the colony was vast and sparsely populated. It stretched north to remote French fur-trading settlements on the upper Mississippi River and west into the Texas borderlands, where Natchitoches served as a key Indian trading post. Relations with Native American tribes required lavish gifts that consumed royal funds. The colony’s nonnative inhabitants numbered about 7,500, and the majority lived along the lower Mississippi River. About a third of them were enslaved Africans, whose population had not increased since the wave of slave imports sponsored by the Company of the Indies in the 1720s. Too remote for regular trading connections with the broader Atlantic world, Louisiana remained what historian Daniel Usner has called a “frontier exchange economy,” where Indians and settlers traded furs and subsistence crops in relative isolation from commercial markets.

Around New Orleans, however, a nascent white Creole merchant-planter class began to emerge in the second-generation colonists who were descended from the French and German settlers. During the colonial period, “creole” (criollo in Spanish) denoted people (free or enslaved) and livestock born and bred in the New World colonies, as opposed to those born in the Old World. With fewer sentimental ties to Europe, white Creoles evidenced a strong determination to maintain their own hard-won social supremacy over officials sent from Europe. This class had dominated the colony through the Superior Council in the final years of French neglect, and, feeling threatened, they mounted a serious challenge to Spanish rule in the Insurrection of 1768.

This rebellion originated when the first Spanish governor, distinguished scholar and explorer Antonio de Ulloa, arrived in New Orleans in March 1766. Because he lacked military reinforcement, he failed to immediately proclaim Spanish sovereignty. Instead, Ulloa governed for two years through the pliant French governor, Charles-Phillippe Aubry. Despite his weak position, Ulloa sought to impose mercantilist trade restrictions and to curtail the Superior Council’s authority. The response of the Creoles, led by attorney general Nicolas de Lafrénière, was to banish Ulloa from the colony in November 1768. Spain, in turn, dispatched a far more determined governor, the Irish-born Alejandro O’Reilly, who arrived in August 1769 with a formidable force of 2,000 troops aboard twenty ships. O’Reilly immediately proclaimed Spanish sovereignty and abolished the Superior Council outright. The leading conspirators were arrested; six were imprisoned in Havana, Cuba, and their property was confiscated. Lafrénière and four others were publicly executed by firing squad.

Spanish rule in Louisiana has been portrayed in history books and articles as merciless military despotism, personified by “Bloody O’Reilly” and his violent suppression of the revolt. In truth, Lafrénière and his co-conspirators were more interested in maintaining local autonomy than in defending French rule. In the decades after 1768, prominent Louisianans lived comfortably and prosperously under Spanish governance.

O’Reilly remained in Louisiana for only six months, but he created an enduring set of institutions and laws. The colonial government he designed was militarily, judicially, and ecclesiastically subordinate to the governor-general of Cuba, and Havana became the main trading center for Louisiana’s merchants. O’Reilly crafted an adaptation of the colony’s existing French laws, bringing them in line with those of Spain; the result, thereafter known as the O’Reilly Code, became the basis of the colony’s legal system. Day-to-day governance became the province of the newly formed Cabildo, a combined municipal council and judicial system where titled seats could be purchased or inherited. O’Reilly also divided Louisiana into parishes, instituted a new slave code that banned Indian slavery, and reorganized the regular and militia forces, including a battalion of free men of color. By the time he handed over power to his lieutenant, Luis de Unzaga y Amezaga, in February 1770, O’Reilly had molded almost every aspect of Louisiana’s civic life into a form that would not change substantially until 1803.

1770–1783: Peace, Partnership, and a Nearby Revolution

Unzaga set the tone for subsequent Spanish governors by embracing Louisiana’s elite Creoles, especially when he married one—Marie Elizabeth St. Maxent, the oldest daughter of a prominent New Orleans planter. Unzaga’s successor, Bernardo de Galvez, later married Marie’s younger sister, Felicité, and many other Spanish officials followed the governors’ example, marrying power with wealth and influence by wedding daughters of the Creole elite. It soon became clear that Spanish rule would allow Louisianans significant autonomy, as the Creole-dominated Cabildo was given wide latitude in local governance. Spain’s administrators focused instead on organizing the military and collecting customs revenues. Nor did Spanish officials impose their language on Louisiana; all Spain’s governors and colonial officials spoke French.

Under Spanish rule, Louisiana’s population began to grow, especially through renewed immigration from various directions. Acadian immigrants (whose descendants are known as Cajuns) were by far the most numerous, having been evicted from their North Atlantic homeland by the British during the French and Indian War. As many as five thousand Acadians arrived between 1762 and 1770; most settled in the bayous and prairie country south and west of New Orleans. Encouraged by Spain to populate undeveloped areas, groups of Canary Islanders, or Isleños, also began to arrive in the 1770s, some settling in Galveztown in Ascension Parish, others traveling downriver from New Orleans to what is now St. Bernard Parish. Settlers from Malaga, Spain, founded the town of New Iberia. Numerous Anglo-Americans also came to Spanish Louisiana, some as urban merchants, others as pioneer settlers lured by free land in the regions farther upriver. After the St. Domingue Revolution (1791–1803), numerous émigrés from that French colony also found their way to Louisiana.

In the early years of Spanish rule, despite the easing of ethnic and national tensions and the colony’s dramatic population surge, economic growth came more slowly. Beginning in 1770 the Spanish crown promoted the development of Louisiana tobacco culture by requiring the royal tobacco monopoly in Mexico to purchase the entire crop from the Natchitoches area. Soon the Louisiana product was in high demand, its quality judged to be among the best in North America. When the Spanish first acquired Louisiana, forty-nine Natchitoches planters harvested eighty thousand pounds of tobacco per year; by 1791 eighty-three plantations there yielded more than seven hundred thousand pounds. The population of both free and enslaved people grew dramatically in this region as well; the number of enslaved people more than tripled between 1765 and 1803, from 269 to 948 people. Tobacco production flourished so quickly that by 1789, warehouses in Mexico and Spain had large surpluses on hand. Mexico stopped importing Louisiana tobacco entirely, and Spain cut its quota to forty thousand pounds, leaving Natchitoches planters without buyers. The market for animal pelts had also collapsed from oversupply in the 1770s. In the 1790s Louisiana planters began to shift away not only from tobacco but also from indigo because that crop, too, proved difficult to sell in the global market. Meanwhile, with no manufacturing to speak of, Louisianans still had to import basic items, such as clothing, shoes, soap, glass bottles, and alcohol. Yet stringent Spanish restrictions on commerce inhibited growth in imports and exports alike.

Unzaga, Galvez, and their successors dealt with this situation in part by turning an official blind eye to the ever-increasing contraband trade. The British and American traders were technically forbidden to do business in Spanish New Orleans, but, in practice, the colony depended on them. In 1772 Unzaga made a brief show of expelling the Anglo merchants, and it seemed to satisfy Madrid. In reality, official tolerance of smuggling became the norm and led to corruption and favoritism. Colonial officials throughout New Spain became so accustomed to complying with royal decrees superficially while skirting their substance that they developed a bureaucratic shorthand for it: obedezco pero no cumplo (“I obey but I do not fulfill”).

As Spanish Louisiana grew, the eastern half of North America was plunged into war when the thirteen British Atlantic colonies declared their independence in 1776. Spain, seeing a chance to reclaim the Floridas from Britain, entered the Revolutionary War (1775–1783) on the side of America (and France) in the summer of 1779. Under Governor Galvez’s personal leadership, a mixed force of Creole militiamen, Spanish regulars, and volunteer free men of color overwhelmed the British garrisons at Manchac and Baton Rouge. The group went on to seize Mobile (Alabama) and eventually Pensacola (Florida), finally capturing the latter outpost in May 1781 after a prolonged siege and unsuccessful British relief efforts. These campaigns made a hero of the dashing Galvez. They also ensured, in the ensuing peace settlement, that the Floridas would be retroceded to Spain after twenty chaotic years under British rule. For the first time, Carlos III’s possessions surrounded the entire Gulf of Mexico—from the Yucatan to the southern tip of East Florida—and it appeared a rejuvenated Spanish Atlantic empire might be poised for a new era of dominance.

Slavery Expansion and Gens de Couleur Libres

As Creole elites began to prosper under Spanish rule, they sought labor for the plantations that now dotted the banks of the Mississippi River as far north as Pointe Coupée. At the same time, British slave traders based in Jamaica began a sharp increase in slave re-exports to Spanish America. Both of these circumstances—increased demand and ample supply—led to a dramatic expansion of African slavery in Louisiana. It was not Spain’s intent to suddenly increase the slave supply, but Spanish governors were not inclined to block the human traffic that their Creole allies so obviously desired. The surge in slave importation in the 1770s and 1780s transformed Louisiana’s economy and culture alike.

Before 1782 the British slave trade was illegal in Louisiana, but ships with a stated destination of Manchac in British West Florida could not be refused entry to the Mississippi River. Once there, they found it easy to sell their human cargo to Louisiana planters. By the time the Spanish legalized this trade in 1782, the enslaved population of Louisiana had already more than doubled. During the next decade, an average of 800 enslaved people per year disembarked in New Orleans, with a peak number of 1,550 arriving in 1787. In the context of the total Atlantic slave trade, these numbers were still small; however, for Louisiana, they were enormous. All together, the thirty-seven years of Spanish rule saw a tenfold increase in the enslaved population, with as many as twenty-nine thousand enslaved men, women, and children arriving in Louisiana—almost all of them African, almost all brought via Jamaica.

This sudden influx “re-Africanized” an enslaved population that had adapted to the Creole, French-speaking ways of the previous regime. African music and drumming began to be heard on rural plantations as well as during Sunday gatherings in an open field (now known as Congo Square) in New Orleans. As enslaved Africans spoke their native languages in the streets and servants’ quarters, the African population became both more visible and more distinctly foreign.

Differences in the laws that governed enslaved people and slaveholders in the Spanish colonial empire led to other significant social changes in Louisiana. Wealthy Creole plantation owners chafed under new rules, resenting the limits imposed on them and fearing that the more lenient policies would spur slave revolts. The mass meetings in Congo Square, for example, could not have taken place under the French regime. The Spanish legal code also made provisions for enslaved workers who were severely abused: they could—and did—lodge formal complaints against their owners. While the overall conditions of slavery remained inhumane and unjust, a few of the people held as property managed to improve their lives. Manumission was more readily available during the Spanish period than it had been under French rule. Both colonial regimes permitted enslaved laborers to earn wages by hiring themselves out when their labor was not needed by their owner. But only the Spanish slave code permitted the practice of coartación, a system of slave self-purchase. Typically, 2 to 4 percent of the enslaved population might be manumitted per year, about half through coartación; women made up a considerable majority of those freed. Coartación accelerated following the two New Orleans fires as the Spanish Crown invested heavily to rebuild the city and hired many enslaved people to do the construction—in effect, financing their ability to purchase their own freedom.

In time, these manumissions led to the formation of a distinct class of gens de couleur libres, or free people of color, who numbered about fifteen hundred by 1803. The libres worked as laborers, storekeepers, and skilled craftsmen; a small minority became slaveowners themselves. The most prestigious male libres bore arms as members of the moreno and pardo volunteer militia companies (the former for free Black men and the latter for mixed-race individuals).

1783–1795: Miró, Carondelet, and a World of Revolution

After the Pensacola campaign, Galvez appointed his aide-de-camp Esteban Rodríguez Miró as acting governor. Appointed full governor in 1785, Miró served until 1791, making his tenure the longest of any Spanish governor of Louisiana. In these years it became clear that the territorial ambitions of the British colonists had been tame compared with those of the newly independent Americans. Louisiana’s connections with the United States, both profitable and destabilizing, soon became the central fact and a key problem of Miró’s administration.

Even before the end of the Revolutionary War, settlers had begun to migrate across the Appalachians into what became the new states of Kentucky and Tennessee. Further south, both Spain and the United States claimed the region around Natchez on the Mississippi River’s east bank. Miró took a twofold approach to this conflict: he offered land grants and promises of religious tolerance to induce Americans to settle in Spanish territory while at the same time encouraging and fomenting separatist movements in the American West. Thousands of American settlers—including such well-known figures as Daniel Boone and George Rogers Clark—gladly swore Spanish loyalty oaths in exchange for lands in Louisiana and West Florida. A settlement along the Ouachita River at Fort Míro (now Monroe) extended Spanish influence northward.

Meanwhile, starting in 1787 Miró negotiated with Gen. James Wilkinson, a veteran of the American Revolution with a spotted record who had settled in Kentucky. In exchange for trading privileges and outright bribes, Wilkinson agreed to encourage separatist sentiment in Kentucky, assuring Miró that the West’s break from the United States was an event “written in the book of destiny.” Wilkinson promised to gauge support for an eventual union with Spain during Kentucky’s statehood convention in 1788. However, separatist sentiment in Kentucky declined after statehood was granted, and Madrid eventually ordered Miró to refrain from further meddling with the American West.

Miró’s successor, Francisco Luis Héctor, barón de Carondelet, governed Louisiana for six years (1791–1797), during which the repercussions of the French Revolution (1789–1799) dominated Louisiana’s affairs, as they did in much of the rest of the globe. Ideologies of liberty and egalitarianism reached New Orleans, eventually affecting almost all ranks of society, from enslaved laborers to wealthy planters. In the nearby French sugar colony of St. Domingue, a slave rebellion in 1791 eventually led to the emancipation of all people enslaved in French territories in 1793. Numerous St. Domingue exiles settled in southern Louisiana, where they exerted a strong influence on local culture. Tension ran high as owners of enslaved people tried to keep news of the events in St. Domingue from reaching their slaves’ ears. Pierre Bailly, a free mulatto businessman who served in New Orleans’s pardo militia, was reported to have declared that he and his allies were awaiting the order from St. Domingue to set a Louisiana coup in motion. Governor Carondelet found Bailly guilty of treasonous activity, and he spent two years in prison in Havana. The Marseillaise, the French national anthem, was requested at the theater; Ça Ira, an opera about the French Revolution, was sung in the streets. And in the western United States, democratic enthusiasm kindled a movement sponsored by Jacobin ambassador Charles Genet to form a citizen’s army to reconquer Louisiana on behalf of revolutionary France.

Carondelet, a conservative aristocrat, faced these developments with revulsion and fear. He renovated the ancient fortifications of New Orleans in anticipation of attack. He suspended slave imports after 1792, fearing a St. Domingue-style slave uprising. Indeed, these fears seemed to be confirmed by the abortive Pointe Coupée revolt of 1795. He banned all immigration by Americans, whom he saw as restless “Kaintocks” just as capable of spreading subversive “French doctrines” as European radicals were. When a group of fifty merchants sent representatives to France to express support for the revolutionary government, Carondelet had the leaders banished from Louisiana.

Unlike his predecessors, Carondelet incurred the bitter enmity of the colony’s wealthy Creoles. They shared his political conservatism but were appalled by the extravagant expenses involved in building up New Orleans’s defenses—particularly since the anticipated attack never came. Above all, they were outraged by his ban on slave imports and his intermittent efforts, also inspired by his fears of rebellion, to promote humane standards in the treatment of enslaved people. Carondelet’s siege mentality, his profligacy, and his personal arrogance led many elite Creoles to become disgusted with the Spanish regime they had found so congenial for the previous twenty years.

New Orleans grew significantly during the 1790s, in spite of—or perhaps because of—catastrophic fires in 1788 and 1794. The fires led to the passage of new laws prohibiting wooden structures, as well as the wholesale rebuilding of most of the town. For the first time the city expanded outside its original walled rectangle (the present-day French Quarter) when the Faubourg Ste. Marie (roughly equivalent to today’s Central Business District) was laid out on the former Jesuit plantation just above Fort St. Louis. The streets St. Charles, Carondelet, and Baronne were named after the king, the governor, and his wife, respectively. Governor Carondelet embarked on ambitious civic improvements—most notably, the construction of a one-and-a-half-mile canal to link the Mississippi River with the Bayou St. John and Lake Pontchartrain. He also bought new streetlamps and created a corps of lamplighters who doubled as night watchmen. The city’s first theater was built in 1792, and two years later Le Moniteur de la Louisiane, the colony’s first newspaper, began publication.

As the city’s population grew, the increasing demand for goods spurred rural agricultural economies. In the Acadian prairie parishes to the southwest and on the Texas frontier near Natchitoches, ranchers raised large cattle herds for export and to feed the local New Orleans market. In the Texas-Louisiana frontier region, ranchers commonly adopted the technique of herding cattle on horseback, using Spanish-style tack on their horses. Maritime products, including hemp, tar, and lumber—all vital to the growing shipping sector—came down the Mississippi from as far away as Kentucky.

1795–1803: Economic Transformation and Spain’s Farewell

In 1795 two events transformed the economic future of Louisiana. In Madrid, American envoy Thomas Pinckney negotiated a treaty that ceded to the United States all Spanish territory east of the Mississippi River and north of the latitude 31° north, including the vital Natchez region. The treaty also granted Americans the right to freely navigate the Mississippi and allowed US merchants a place in New Orleans to deposit their goods for duty-free re-export. And just outside New Orleans, at a plantation on the present-day site of Audubon Park, planter Etienne Boré successfully produced refined sugar for the first time in Louisiana.

The St. Domingue Revolution had drastically curtailed that island’s sugar production, and within a few years of Boré’s “miracle,” Louisiana planters abandoned indigo to invest in sugarhouses and imported cane plants. Boré’s brother-in-law, wealthy German Coast planter Jean-Noël Destréhan, pioneered the use of bagasse (the crushed cane stalks that are a by-product of milling) to cover fields in anticipation of frosts as well as to fuel the sugar distilling process. Within a few seasons, more than one hundred plantations around New Orleans were producing six million pounds of sugar each year through the labor of nearly two thousand enslaved workers.

Meanwhile, the development of the cotton gin transformed the agricultural landscape of upcountry Louisiana, as it did throughout the American South. By 1802 there were twenty-five cotton gins along the Red River, and cheap, profitable cotton soon replaced tobacco as the crop of choice on Red River plantations, on the upper Mississippi, and in the western prairies. By 1796 Julien Poydras, the wealthiest landholder of Pointe Coupée, switched his plantations to cotton—as did hundreds of smaller-scale planters who could afford neither the massive enslaved labor force nor the prime lowland real estate required to produce sugar. Cotton culture also predominated in what would later become the Florida Parishes, especially along the Mississippi River near Baton Rouge, where a predominantly Anglo-American planter population had sworn allegiance to Spain in exchange for generous land grants. (Technically part of Spanish West Florida rather than Louisiana, the Florida Parishes would be joined to the State of Louisiana in 1812.) In New Orleans, commerce soon centered on cotton trading, fueled by the ever-growing demand from British merchants in Liverpool and textile mills in Manchester, England.

Along with the new cash crops, trade with the United States fueled the colony’s sudden growth after 1795. Increasing numbers of flatboats descended the Mississippi, laden with pork, hemp, and flour from as far away as Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. At the same time, coasting vessels from the Atlantic ports came upriver to sell British trade goods and pick up sugar and cotton cargoes. In the century’s final years, a new cohort of Yankee merchants, such as land speculator and banker Daniel Clark, brought a network of interlinked trade and credit contacts in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, Baltimore, Maryland, and New York to Louisiana. New Orleans was now both a strategic point of transshipment and a major market in its own right. The long-obscure colonial outpost had finally become a city with ambitious plans for urban development and municipal improvements. The Cabildo, St. Louis Cathedral, and the Presbytere had been rebuilt by the town’s leading citizen, Don Andrés Almonester y Roxas. Together the buildings formed an imposing façade on the Plaza de Armas (now known as Jackson Square), facing the bustling levee and a river filled with ships.

But even as Spanish Louisiana began to thrive, Spain itself was deeply troubled. Now ruled by the meek, indecisive Carlos IV, the country was reluctantly dragged into a ruinous war against Great Britain. Increasingly subject to the influence of France’s new first consul, Napoleon Bonaparte, the Spanish agreed in October 1800 to cede Louisiana back to France in the secret Treaty of San Ildefonso. In exchange, Spain received a small kingdom in Tuscany. The treaty remained a secret because Bonaparte wanted to conclude the Peace of Amiens with Britain before implementing his grand colonial scheme—an undertaking that would make Louisiana the wheat-growing breadbasket for a reconstructed, slave-based sugar colony in the Caribbean. But when the army sent to subdue and re-enslave the people of St. Domingue collapsed, Bonaparte abandoned the whole plan and sold Louisiana to the United States, violating his agreement with Spain that the province would not be transferred to any third party.

Despite French ownership of the colony, Louisiana officially remained Spanish for three more years and was administered by governors Manuel Gayoso de Lemos, the Marquis de Casa Calvo, and Juan Manuel de Salcedo. News of the Louisiana Purchase reached New Orleans in August 1803 and met with mixed reactions. Some Creoles looked back fondly on the years of relative stability under Spanish administration, but many others, especially merchants, anticipated prosperity, free trade, and self-rule in the American republic. On November 30 the Spanish flag was lowered in the Plaza de Armas and—with several hundred soldiers, militiamen, and townspeople looking on through a chilly rain—the Spanish colonial era’s four decades in Louisiana came to a quiet end.

Spain, however, continued to exert authority and influence in large areas of present-day Louisiana well after 1803. Rumors that the colony would be ceded back to Spain in exchange for the Floridas, encouraged by Spanish officials who denied the purchase’s legitimacy, undermined American rule. In West Florida, now claimed by both the United States and Spain, prosperous planters were happy to remain under the Spanish flag. Not until the 1810 West Florida rebellion were American troops able to claim the region. Louisiana’s western border with Spanish Texas was also in dispute because neither the Louisiana Purchase agreement nor the previous treaties between Spain and France had specified exactly where the line should be. After Spanish forces blocked an expedition sent by President Jefferson to explore the Red River in 1806, Wilkinson (now governor of the northern Louisiana Territory) and Lt. Col. Simón de Herrera agreed to create the Neutral Strip, a swath of land east of the Sabine River that neither country would officially claim. Not until the signing of the Transcontinental Treaty in 1819 were Spain’s frontier claims finally settled and Louisiana’s western border clarified.

Legacies of Spanish Colonial Louisiana

Louisiana was an anomaly in the Spanish Atlantic empire. Spain’s core colonies—the viceroyalties of New Spain and Peru—were structured primarily to extract mineral wealth mined by enslaved natives. Peripheral colonies like Louisiana and Cuba were valued primarily because they helped keep the riches flowing from the mines of Mexico and the Andes. Nowhere in the Americas besides Louisiana did Spain administer a colony based on staple agriculture, with a population of European-descended settlers and enslaved Africans. Spain’s rulers were not particularly adept at, or interested in, governing such a colony—and were much less so in a period when geopolitical upheavals were bringing that colony into an ever-closer relationship with the fast-growing American republic.

Spain’s thirty-seven years of colonial rule left few obvious traces in Louisiana. In the words of David Weber, the foremost historian of Spain’s colonial frontier, “Louisiana became Spanish more in name than in fact.” The Spanish language was never widely adopted, and Spanish settlers never arrived in large numbers. Those who did immigrate, like Spain’s colonial officials, assimilated to French Creole customs rather than the other way around. Yet Isleño communities persisted—some continuing by virtue of their geographic isolation to preserve their culture to the present day. Similarly, former frontier outposts have retained some of their Spanish colonial flavor—literally, in the case of the tamales celebrated in the town of Zwolle and in Natchitoches’s meat pies, which resemble empanadas. Jambalaya, strikingly similar to paella, is embedded in the foodways of Ascension Parish and most of South Louisiana. In southwestern Louisiana the Spanish cultural legacy survives in cattle herding and cowboy culture.

Today the most visible evidence of Spanish rule is undoubtedly the architecture in the oldest portions of New Orleans—especially in the ironically named “French” Quarter, where numerous structures from the Spanish colonial era remain intact. The distinctive style of the architecture resulted from Spanish building codes, enacted after the great fires of 1788 and 1794, that required stucco exteriors and tiled roofs. Settlers from southern Spain built homes that incorporated their customary patios and long iron balconies.

In the Spanish period, Louisiana developed all the salient attributes that characterized the state during the antebellum period: a large African population of both enslaved people and gens de couleur libres and a slave-based plantation system producing cotton and sugar that was dominated by an elite Creole planter-merchant class. During this period New Orleans also emerged as the center of commercial and social life, influencing the broader region to a degree that few colonial cities did. Another enduring legacy of the Spanish period—less tangible but more profound—was the transformation of Louisiana’s racial order. The so-called three-caste race system of whites, enslaved people, and free people of color was never stable and always contested. The gens de couleur libres aspired to, but never attained, status equal to whites, while whites tended to consider all people of color their inferiors, whether they were enslaved or free. But the three-caste system, more typical of South American societies, nonetheless persisted—especially in New Orleans—throughout the antebellum period and beyond. Even today, many New Orleanians of mixed race prefer to identify themselves as Creoles of color rather than as African Americans.

The most consequential aspect of the Spanish colonial era for Louisiana’s subsequent development was the regime’s symbiotic relationship with elite Creole planters and merchants. Drawn from a small number of interrelated families in New Orleans and nearby parishes, this powerful class led the Cabildo under Spanish rule and continued to dominate the conservative city council during the early American period. They had a near monopoly on sugar planting, since high capital requirements made it difficult for newcomers to enter the industry. They also held sway over the social world of early American New Orleans. Governors Unzaga, Galvez, and Miró married into elite Louisiana families, as did other powerful Spaniards, fusing their interests and ideologies with those of the colony’s wealthiest planters and merchants to form a cohesive ruling caste. These families’ economic and cultural power, their conservative social and racial outlook, and their aristocratic pretensions continued to dominate Louisiana well after the ancien regime (or “old order”) had nominally yielded to the new world of American democracy.