Reverse Freedom Rides

In 1962 and 1963 white Citizens’ Councils organized “Reverse Freedom Rides,” parodying the Civil Rights Movement’s Freedom Rides by providing one-way tickets for Black Americans to northern and western cities.

Northwest Louisiana Archives, Louisiana State University-Shreveport

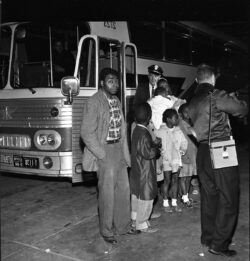

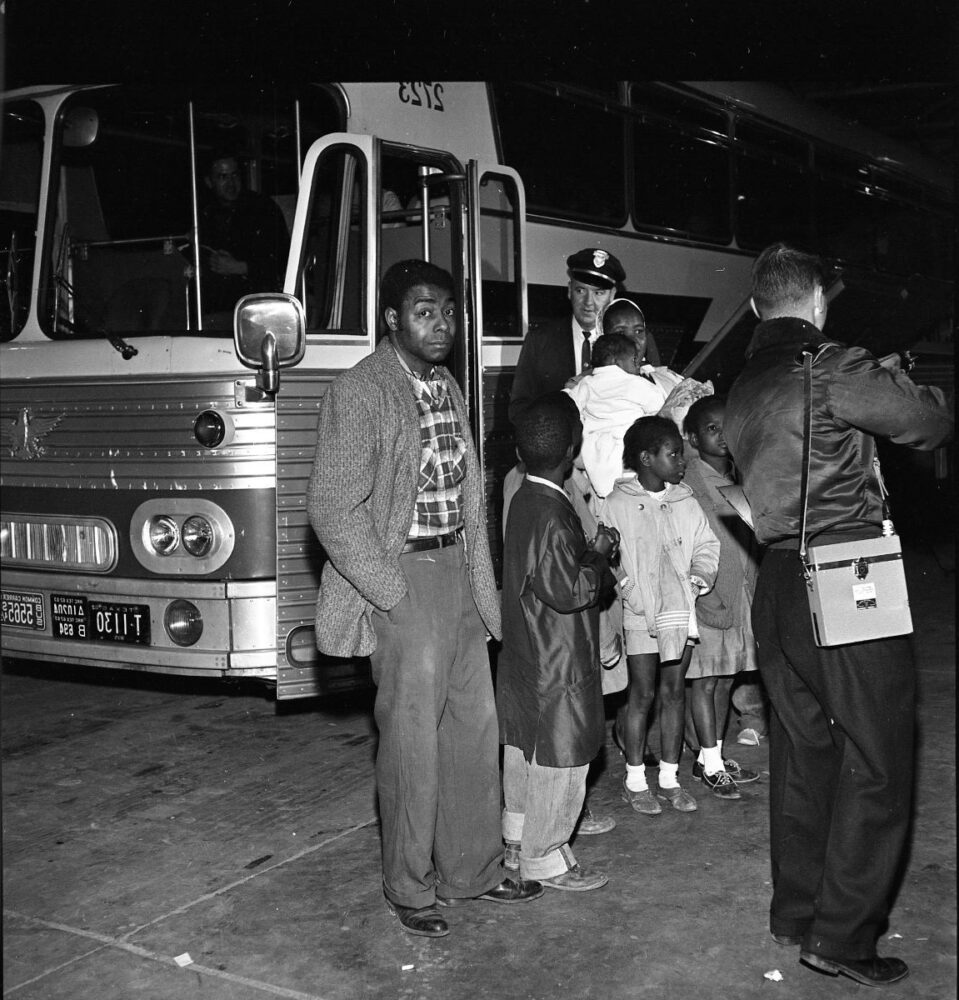

Alan Gilmore, his wife, and their eight children leaving Shreveport for Trenton, New Jersey, with bus tickets and $75 in spending money provided by the Citizens' Council of Louisiana.

Louisiana was a base for “Reverse Freedom Rides,” attempts by segregationists in 1962 and 1963 to bus urban Black southerners to northern and western cities. Conceived by white Citizens’ Councils, they parodied the Freedom Rides organized by the Congress of Racial Equality(CORE) and the Nashville Student Movement in 1961. Those who signed up were given free one-way bus tickets and were promised high-paying jobs and free housing. Such promises were intended to lure Black people in but were baseless. These reverse freedom riders became, in the words of the Shreveport Journal, “pawns in a tragic struggle.”

The Reverse Freedom Rides were part of massive southern resistance to the 1954 US Supreme Court decision overturning segregation in Brown v. Board of Education. The themes of victimhood and revenge were evident in the chosen destinations: the residences of the Kennedys, Chief Justice Earl Warren, and US Attorney General Nicholas Katzenbach. The project was organized by George Singlemann of the New Orleans Greater Citizens’ Council in retaliation against what researcher Clive Webb termed “northern liberals.” He met with Ned Touchstone, head of the North Louisiana “Freedom Bus North” movement, and other leaders of the Louisiana Association of Citizens’ Councils in Shreveport in May 1962 to plan their strategy. They offered various rationales to make their project seem “respectable.” Touchstone insisted the Reverse Freedom Rides represented “a sincere desire” to help jobless Black southerners migrate north, where they could receive greater economic and social opportunity. He claimed that they were “begging for assistance.” Shreveport attorney Charles Barnett asserted that the Reverse Freedom Rides were merely a “Christian gesture” to help less fortunate Black southerners find new homes in the north. What organizers wanted most, however, was to make a political statement about desegregation and what they considered northern hypocrisy. As Singlemann explained in an interview, northerners had been advocating on behalf of Black people throughout the nation, but “when it comes time for them to put up or shut up, they have shut up.” Ride organizers advertised through flyers and radio commercials to attract Black southerners to accept bus tickets bought with money raised by the Citizens’ Councils. Their ideal recruits were single mothers with many children and men who had become entangled in the criminal justice system. They targeted people who, as they saw it, were burdens on public resources.

The Boyd family of New Orleans was the first to respond to the advertising. Louis Boyd was an unemployed longshoreman. With only a fifth-grade education and a large family, he was destitute and desperate but had little chance of getting another job in New Orleans. He, his wife, and eight children left New Orleans on a bus for New York City in April 1962 with their worldly possessions in three cardboard boxes and a footlocker. There was no one waiting for them when they arrived and nowhere for them to go. Boyd was eventually able to get a job in New Jersey. Many like him were not so lucky.

Lela Mae Williams, a single mother, and seven of her nine children were sent from Little Rock, Arkansas, to Hyannis, Massachusetts. She was promised a good job, good housing, and a personal welcome from US President John F. Kennedy’s family. None of those things awaited her. Margaret Moseley, a longtime civil rights activist in Hyannis, recalled the deception of the rides in a live televised interview a few years before her death, stating: “It was one of the most inhuman things I have ever seen.”

The program’s reported success was also inconsistent. The New Orleans–based Black newspaper Louisiana Weekly reported that “riders of the ‘Freedom Bus North’ project, sponsored by the White Citizens’ Council of Greater New Orleans, are meeting with various types of experiences—mostly unpleasant.” While a few were welcomed and given jobs, the majority were “disillusioned” with the realization that they had been “used by segregationists,” the paper reported. Rezzie Moffet, who went to Chicago, and Junius Eli, who was sent to New York City, returned to New Orleans only a few weeks later, saying they felt duped. The Citizens’ Council newsletter, the Councilor, by contrast, claimed the “Freedom Bus North” movement was “very successful.”

The intention had been to send thousands of people north, but only a few hundred Black people—mostly from Louisiana and Arkansas—accepted tickets to New York, New Hampshire, California, Massachusetts, Minnesota, and Idaho. The largest number went to the bus stop closest to the Kennedy compound at Hyannis Port on Cape Cod because they blamed the president for desegregation. Condemnation of the scheme came from all parts of the United States and even from Canada. By the spring of 1963, criticism of the controversial southern segregationist program reached a crescendo even in the South, and the Citizens’ Council ran out of funds to continue its operation.