Ned Touchstone

Ned Touchstone was an influential figure in the Louisiana White Citizens’ Council, editing and publishing the organization’s official publication and leading the Reverse Freedom Rides campaign in North Louisiana.

Northwest Louisiana Archives, Louisiana State University-Shreveport

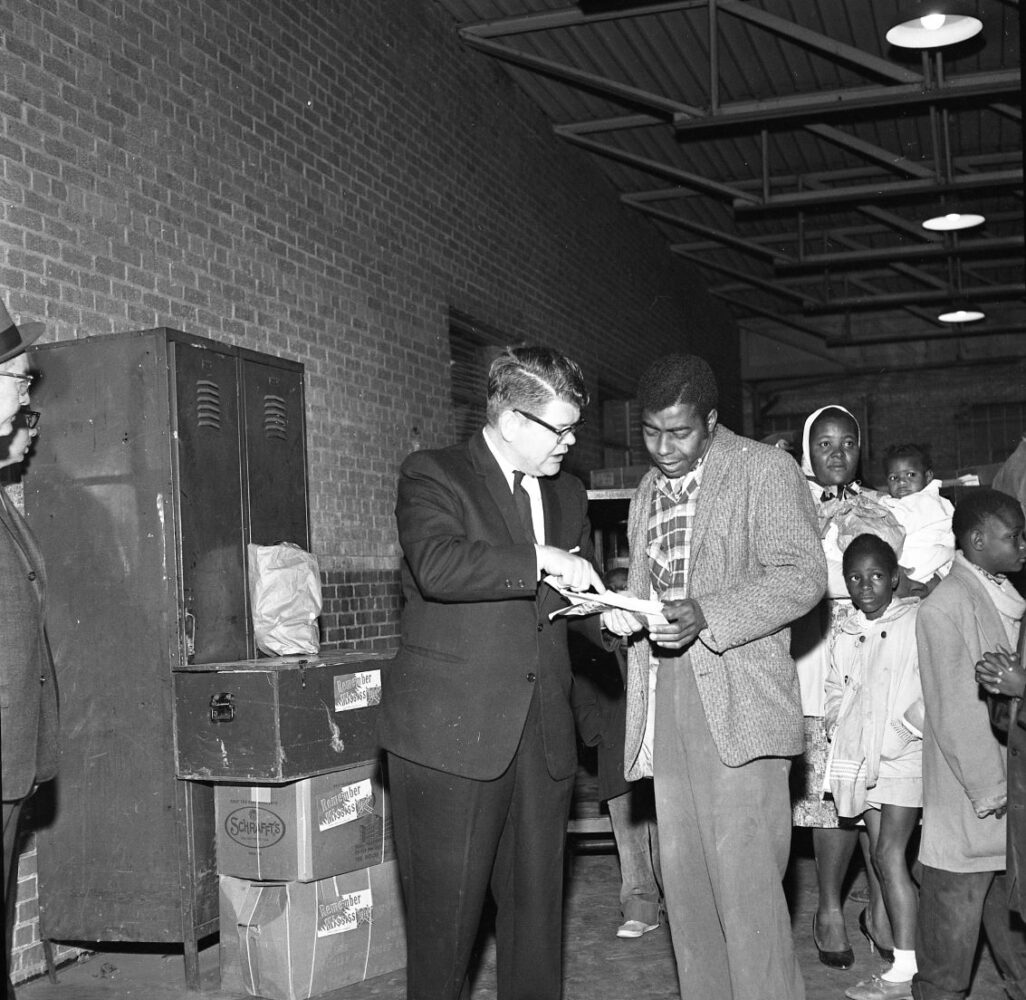

Ned Touchstone (left) talks with Alan Gilmore before Gilmore and his family departed from Shreveport to New Jersey on a Reverse Freedom Ride.

Ned O’Neal Touchstone was a professional researcher, editor, and publisher of the weekly Bossier Planters Press and owner of a retail bookstore in northwest Louisiana during the mid-twentieth century. He was also a right-wing political activist, a board member and secretary of the Louisiana Citizens’ Council Inc., director of the “Reverse Freedom Rides” campaign for North Louisiana in the early 1960s, and editor and publisher of The Councilor, the official publication of the Citizens’ Council organization he promoted. Touchstone earned a reputation as an editor and distributor of racist hate literature for more than twenty years.

Background and Early Career

Touchstone was born September 7, 1926, in the sawmill town of Florien in Sabine Parish but grew up in the Shreveport-Bossier area. He enlisted in the US Army on December 13, 1944, and was assigned occupation duty with the Seventh Infantry division in Seoul, Korea, where he served as provost court clerk correspondent for the Stars and Stripes and as a public relations representative. He served in the army for two years and was discharged on October 28, 1946.

Touchstone studied government and journalism at Louisiana State University (LSU), where he edited the university handbook and a humor magazine, Kickapoo. After leaving LSU Touchstone worked as an administrative assistant to Rep. Overton Brooks of Shreveport of Louisiana’s Fourth Congressional District. Touchstone researched and authored the bill to construct the Veterans’ Hospital in Shreveport that bears Brooks’s name. He became a contributing editor of the American Mercury magazine, managing the publication for a time in the 1950s. He appeared in the masthead as “financial editor” until the publication closed in 1981. He was also on the board of the Liberty Lobby, an anti-Semitic group that operated from 1958 to 2001.

When the Brown v. Board of Education decision ignited massive resistance to public school desegregation in the South in 1954, Touchstone was prepared. The Citizens’ Council of Louisiana, Inc. formed in April 1956 and tapped him, a well-known segregationist and newspaper publisher in North Louisiana, to handle media promotion. He presided over the first meeting when the Shreveport Journal announced the organization of a local Citizens’ Council in Bossier City in April 1956.

During the 1960 presidential campaign that pitted Democrat John F. Kennedy against Republican Richard M. Nixon, Touchstone’s newspaper endorsed a states’ rights “free electors” scheme. “Free electors” were not formally bound to the major party candidates. In theory by selecting “free electors” in each state, the South could gain favorable federal policy on desegregation in exchange for its electoral votes. In an article in the Shreveport Journal on November 4, 1960, Touchstone urged his readers to cast a protest vote on November 8 and vote for free electors because “pinkos, integrationists, and professional politicians” were pressuring Gov. Jimmie Davis and had taken over both political parties.

Another of Touchstone’s early media initiatives included an attempt to censor media by monitoring network television and radio programs for examples of “leftist news-slanting and socialist brainwashing.” An organization calling itself “Monitor South” planned to conduct round-the-clock monitoring of television and radio programs for perceived anti-southern bias. Touchstone served as its executive director. In Shreveport Journal articles on December 13, 1960, and January 11, 1961, Touchstone claimed that Monitor South launched to protect sagging southern property values. He asserted that “the South is a major target of ultra-liberal and pink [communist] elements in the East” that created a false image of the South through TV and radio programs. He alleged that these programs portrayed “all white southerners as ignorant, degenerate, and villainous,” which created a negative impression of the South that he believed would weaken the demand for property in southern states. Washington Post columnist Lawrence Lourent likened the project to book burning. Touchstone boasted that if Monitor South attracted “deliberate defamation of the South” from the Washington Post and NBC, its needling had been successful. Monitor South continued operations as late as 1967, when Touchstone ran for Louisiana Superintendent of Education on a segregationist platform. He was defeated by incumbent William J. “Bill” Dodd.

Touchstone also played a prominent role in the Citizens’ Councils’ best-known effort to target government officials advocating desegregation, notably President John F. Kennedy, Attorney General Robert Kennedy, Assistant Attorney General Nicholas Katzenbach, and Chief Justice Earl Warren. Touchstone directed the North Louisiana portion of the Freedom Bus North Movement of 1962 and 1963. Often referred to as “Reverse Freedom Rides,” a parody of the Freedom Rides organized in 1961 by the Congress of Racial Equality(CORE) and the Nashville Student Movement, the Freedom Bus North Movement targeted Black people, advertising and offering them free, one-way bus tickets to mostly northern cities, falsely promising high-paying jobs and free housing. In a television interview Touchstone justified the scheme, claiming the North was “sending down busloads of people here with the express purpose of violating our laws, fomenting confusion, trying to destroy one hundred years of workable tradition and good relations between the races.” Elsewhere, even in the South, people saw the scheme as a cruel effort to lure Black people out of the South and use them to take revenge on perceived political enemies. By 1963 the campaign ended.

The Councilor and Right-Wing Literature

When Touchstone became editor of The Councilor in 1962, the move sparked division among board members over the future of statewide Citizens’ Councils and the expansion of Touchstone’s career as a purveyor of “radical right” literature. Citizens’ Council executives Charles Barnett and William Rainach believed Touchstone and executive board member Courtney Smith were trying to take over the Citizens’ Councils of Louisiana, Inc. organization. The dispute led to Touchstone and Smith’s expulsion, although they were later reinstated. Touchstone continued to publish The Councilor into the early 1980s as it became increasingly dominated by conspiracy theories linking racism, antisemitism, communism, and globalism together. In addition to The Councilor, Touchstone distributed and received right-wing literature for a living through his printing business and bookstore in Shreveport. He kept an inventory of books and pamphlets by popular white nationalist authors like Thomas Dixon (author of The Clansman), Frank Capell, Earnest Sevier Cox, John Beaty, Gerald L. K. Smith, and Elizabeth Dilling, as well as many John Birch Society publications.

Despite Barnett and Rainach’s accusations, Touchstone never aspired to “take over” the Citizens’ Council. Media promotion afforded him a more powerful position. Rainach died in 1978. The Councilor and Touchstone’s retail book and pamphlet distribution business continued to thrive for at least six more years. Touchstone was known for his vast knowledge of facts and ability to recall complete passages from the thousands of books he had read and collected. He was a world traveler and could discuss nearly any subject intellectually with any expert. His expertise included ancient history, languages, sciences, poetry, art, and the Bible. His intellectual acumen, talent as a writer, and belief in his causes were unquestioned but tarnished by the otherism and hatred that marked them. He died at his home in Lake Palestine near Tyler, Texas, on July 26, 1988.