Winter 2024

A Long Arc of Injustice

A new exhibition explores the historical links between the institutions of slavery and mass incarceration in Louisiana

Published: December 1, 2024

Last Updated: February 28, 2025

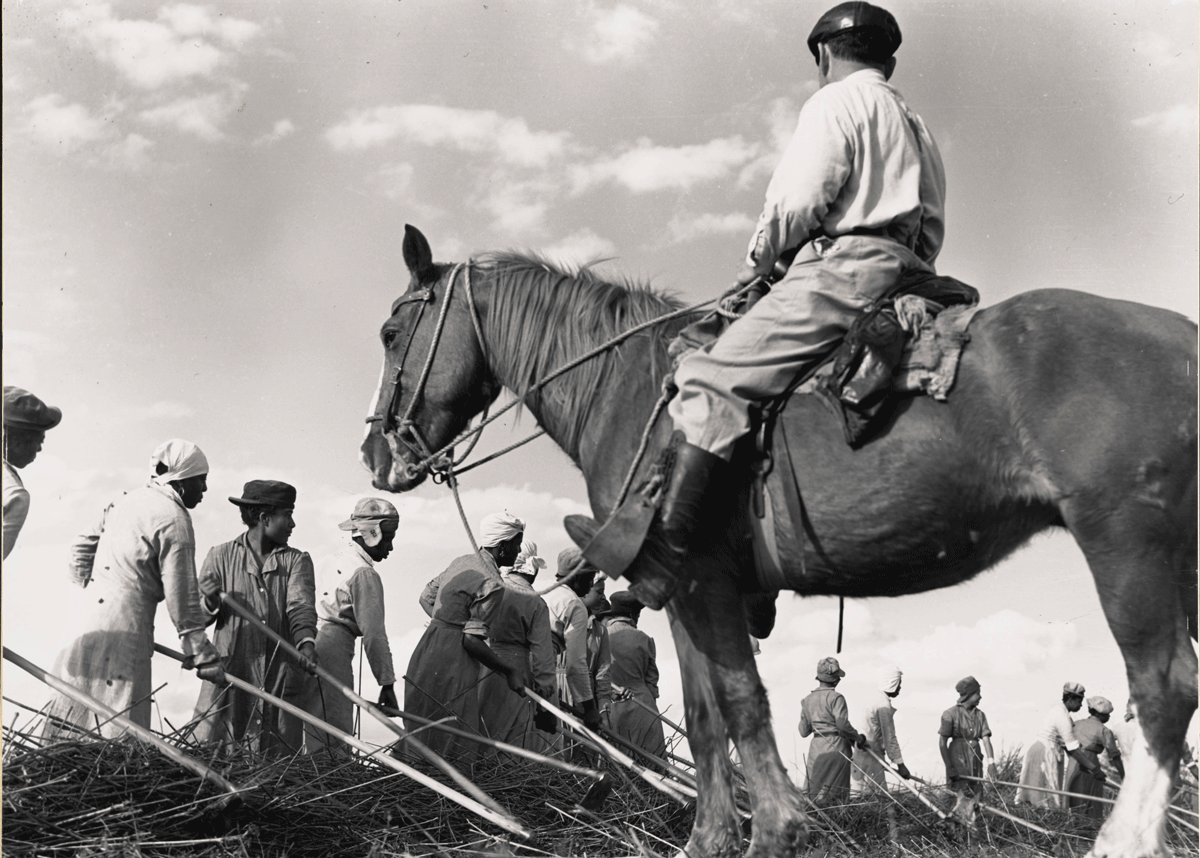

HNOC, 2018.0513.9

Fonville Winans, Angola Hoers,1938. Gelatin silver print.

When Curtis Davis arrived as a prisoner at the Louisiana State Penitentiary in 1992, he was sent directly to the fields. He picked cotton and fruit on a plantation property that has operated continuously with forced labor for nearly two hundred years, never making more than twenty cents an hour until his release in 2016. He spoke about his experience in one of ten video testimonials featured in Captive State: Louisiana and the Making of Mass Incarceration, on view at the Historic New Orleans Collection through February 16.

“Slavery has never been abolished in these United States of America,” Davis says. “It has been codified into law through the Thirteenth Amendment and the Louisiana Constitution.”

Davis articulated the thesis of Captive State: that the institutions of slavery and mass incarceration are historically linked. The Thirteenth Amendment enshrined this connection in the US Constitution in 1865 by abolishing slavery “except as punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted.” Once the hub of the domestic slave trade, Louisiana now leads the world in incarceration, with Black people disproportionately affected. Captive State traces the roots of this inequity back to the founding of the state.

“Captive State documents how slavery and incarceration were mutually reinforcing in ways that have had long-term impacts on people in this state, particularly Black Louisianans,” said Eric Seiferth, the exhibition’s co-curator.

A six-member advisory board of people with experience inside and outside of the incarceration system helped develop the exhibition. Two landmark legal documents anchor its narrative. The first is the Code noir, a set of laws issued by the French crown in 1724 that regulated the lives of enslaved and free Black people. The other document is the Louisiana Constitution of 1898, written, according to one of its authors, “to establish the supremacy of the white race in this State.”

“Slavery has never been abolished in these United States of America….It has been codified into law through the Thirteenth Amendment and the Louisiana Constitution.”

Davis’s story is one of many featured in Captive State that convey the human consequences of this history. Visitors read about Peggy, an enslaved woman found guilty of killing another enslaved woman, and see the 13.5-pound iron ball and chain that she wore for three years as punishment. There’s the story of Cezar, an enslaved man in New Orleans who confessed to crimes after being tortured and was sentenced to a brutal public execution. Visitors also view a letter written by Rufus Kinsman, a free Black sailor who described the “hell” of being jailed, whipped, and forced to work on a chain gang after being falsely arrested as a fugitive slave. A circa 1821 lithograph on display is the earliest known depiction of a chain gang.

Louisiana began leasing out state prisoners for their labor in 1844. After the abolition of slavery in 1865, this system of convict leasing became the state’s primary method for controlling Black people and holding them in captivity. A map and data graphic help illustrate the brutal era of the convict lease, during which thousands of prisoners died.

The 1898 state constitution codified this system of forced convict labor and returned custody of prisoners to the government. Three years after its passage, the state purchased the plantations owned by the last convict lessee and turned them into the new Louisiana State Penitentiary, better known as Angola. The constitution also made it possible to convict a person of a felony with only nine of twelve jurors in agreement. The split-jury law led to more guilty pleas and verdicts, supplying a steady stream of prisoners to the state.

A large graphic depicts how Louisiana has come to lead the United States in incarceration rates over the last century. Rates spiked locally and nationally in the latter half of the twentieth century, as legislators in the 1970s and subsequent decades began writing a litany of new “tough-on-crime” penalties. These, in concert with split-jury verdicts, sent more Louisianans to prison for longer terms than ever before. An animation shows the correlated buildup of the Orleans Parish jail complex over the last 120 years. Three-dimensional objects—including a bed, commode, and jail intake materials—bring the realities of the contemporary jail experience to the fore.

Steven Garner, Vashon Kelly, Robert Matthews, Scott Meyers, Diego Zapata, The Joy of Freedom, 2010. Quilt. HNOC, gift of Lori Waselchuk, 2016.0298.7

Human stories underscore the interpretation. Visitors can view 250 photographs of people incarcerated at Louisiana prisons from Deborah Luster’s One Big Self: Prisoners of Louisiana, as well as images of the hospice program at the Louisiana State Penitentiary from Lori Waselchuk’s Grace Before Dying photographic series. Hospice program volunteers Steven Garner and Gary Tyler were the lead artists behind two quilts also on display.

The exhibition ends on a hopeful note, telling the story of how in 2018 Louisiana voters finally struck down the 1898 nonunanimous jury law. Visitors exit through a gallery designed for engagement and reflection. A ninety-minute tour also offers visitors an opportunity to engage more deeply. At its core, Captive State encourages us to contemplate our shared responsibilities in this system—and our shared humanity.

“I just pray that people can realize that there are everyday people behind these walls who love, who get sad, who hurt, who are happy, who have dreams,” says Daryl Waters, the subject of another featured testimonial. “You can lock us up, but you can’t stop us from being human beings.”