Non-Unanimous Juries

A segregation-era law voted down in 2018 and deemed unconstitutional in 2020

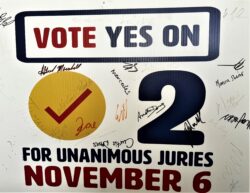

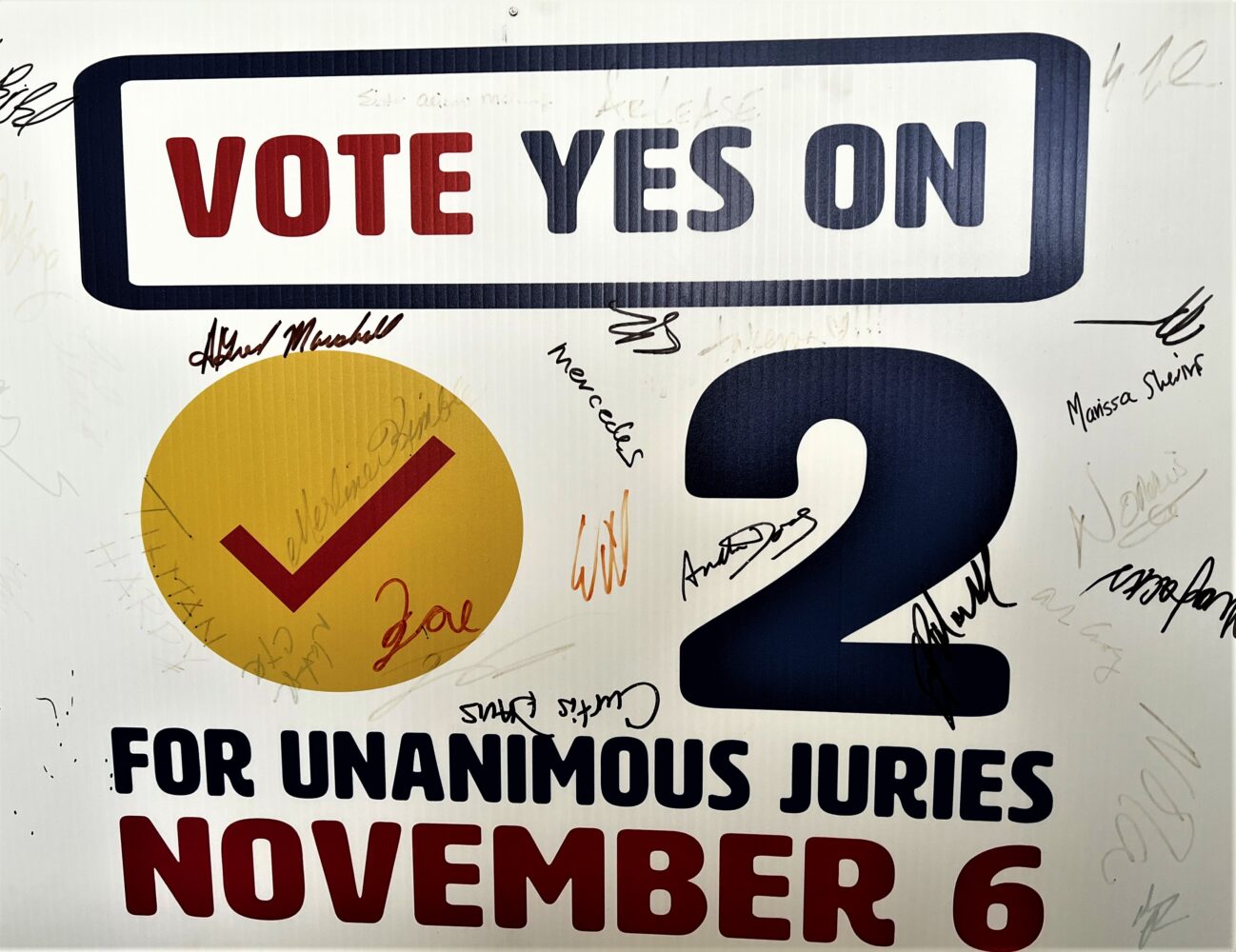

Courtesy of Private Collection

Yes on 2 Campaign Sign. Jamila Johnson for Promise of Justice Initiative

The non-unanimous criminal jury in Louisiana was an American anomaly. Most state criminal systems, many adopted during the colonial period, were built on the English common law, which relied on unanimity as the bedrock of fairness. After the 1803 Louisiana Purchase, despite many remaining vestiges of the Napoleonic Code, Louisiana’s jury standard was built on that common law model. In the post-Reconstruction period, however, some in Louisiana believed that jury unanimity worked against the white supremacy that state leaders sought to uphold following emancipation and the passage of the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth amendments. Delegates to the 1898 Louisiana constitutional convention formalized a new standard requiring nine out of twelve jurors to concur for a conviction. Two racially motivated reasons prompted the change. First, the state’s convict-leasing system functioned as a monopoly administered by S. L. James, a former Confederate major whose prison camp at Angola benefitted from as many convicts as he could acquire, the vast majority of them Black. Second, many whites saw Black jury service in metropolitan areas as “diluting” jury pools and helping Black defendants escape punishment for their crimes. For example, sixteen percent of New Orleans’s jury-eligible population at the time was Black, meaning that any representative jury in the city would include two Black participants. Creating a system that allowed conviction with only nine members of the jury concurring essentially eliminated potential Black dissent on juries. It did so without fully barring non-whites from participating, which could potentially prompt a federal investigation for violating the Fifteenth Amendment.

The Politics of Jim Crow

The state’s nonunanimous jury provision was aligned with its broader Jim Crow project, and the first legal test of Louisiana’s racialized jury system came with the declared constitutionality of segregation laws. On the same day that the US Supreme Court decided Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), opening the door to broad-based segregation in the state, it also decided Murray v. Louisiana (1896). Murray upheld the murder conviction of James Murray, a Black man who had appealed because of the racial makeup of his grand jury. As a result, the court that justified Jim Crow also justified Louisiana’s jury selection, upholding the arguments of white officials that “a great many colored men were summoned [to be jurors], and there was no discrimination against colored men.”

In the following decades Murray v. Louisiana was one of many jury-related cases in which a variety of twentieth-century petitioners appealed convictions based on the fact that, because of a non-unanimous conviction, they would not have been declared guilty in almost any other state. However, Oregon passed its own non-unanimous jury law in 1934, prompted by a series of ethnic disputes in the Pacific Northwest. When one of the Louisiana appeals advanced to the US Supreme Court in the early 1970s, it would be decided in conjunction with a similar case from Oregon. That case, Johnson v. Louisiana (1972), was first argued before the court in 1971 and then reargued the following year. Frank Johnson had been convicted of armed robbery by a non-unanimous jury. In a narrow 5–4 ruling, one that came after Richard Nixon appointed two new conservative justices between the times of the first and second arguments before the court, Justice Byron White’s majority opinion ruled: “That rational men disagree is not in itself equivalent to a failure of proof by the state, nor does it indicate infidelity to the reasonable-doubt standard.”

Constitutional Change in Louisiana

Following the Johnson decision, Louisiana produced another in a long line of state constitutions. Some delegates to the state’s 1974 constitutional convention hoped to use the court’s narrow verdict to eliminate the non-unanimous standard while others saw it as a validation of the practice. Ultimately Walter Lanier Jr., an assistant district attorney in Lafourche Parish, brokered a compromise between the two factions. The compromise changed the requirement to ten concurring jurors for a non-unanimous conviction, despite delegates admitting that the burden of such convictions overwhelmingly fell to minority defendants.

Legal challenges continued even after the change, but there was also a push through academic scholarship and popular writing that pointed to the historical motivations of the practice and inequities in its modern outgrowth. Much of that work began with the efforts of Southern University law professor Angela Allen-Bell and Louisiana ACLU director Marjorie Esman, who wrote independently about the practice before combining their efforts. Together they presented a panel on the subject featuring activists Calvin Duncan, who spent years working on the issue after wrongfully serving twenty-eight years in custody at Angola, and Will Snowden, who litigated the practice as a public defender and who worked to educate the community about it as the founder of the Juror Project. Afterword, a flurry of op-eds and advocacy work ensued to end the practice. Allen-Bell in particular translated her original academic work to a public audience in a series of articles, interviews, media collaborations, videos, presentations, and community talks. Along with Esman and Tulane University professor Heather Johnson, she also authored the American Bar Association’s Criminal Justice Section Resolution and Report urging “Louisiana and Oregon to require unanimous juries to determine guilt.” The resolution passed at the association’s spring 2018 Criminal Justice Council Meeting and changed policy at the association level. Allen-Bell also consulted with the New Orleans Advocate, which produced the groundbreaking 2018 “Tilting the Scales” series, which would later win a Pulitzer Prize for exposing racial disparities in the jury selection and conviction process associated with the non-unanimous jury law. Simultaneously, a campaign by former Grant Parish district attorney Ed Tarpley, who was in the audience for that original panel discussion, helped popularize the issue. In 2016 he authored a resolution adopted by the Louisiana State Bar Association that called on the legislature to implement unanimous criminal jury verdicts in Louisiana.

The work of Esmen, Allen-Bell, Duncan, and Snowden also targeted the state legislature, where Representative Edmond Jordan of Baton Rouge first submitted a constitutional amendment to overturn the practice in 2018. In March of that year, State Senator Jean-Paul Morrell of New Orleans introduced the amendment in his own legislative body. After it passed both houses of the legislature and went before the public for a vote, a bipartisan group of advocates came together to argue for the change.

The public campaign was led in large measure by the Unanimous Jury Coalition, founded by Ben Cohen of the Promise of Justice Initiative and led by Norris Henderson. Henderson had been wrongly incarcerated for twenty-seven years after a non-unanimous conviction, and upon his release in 2003, he became an activist, which led him to create Voice of the Experienced (VOTE) and other criminal justice reform organizations. “We are at a crossroads, with an opportunity to right this long-standing wrong,” wrote Henderson. “It’s time to come together, reject prejudice in all its forms and build a future in which everyone is valued and supported.” Henderson and Cohen’s efforts to help secure the amendment’s approval were aided by the ACLU, the Innocence Project of New Orleans, and the Louisiana Public Defender Association, working in conjunction with Allen-Bell, Duncan, Snowden, and Tarpley, as well as many others. The nonunanimous jury system finally fell in 2018, when the public voted to approve the constitutional amendment.

Declared Unconstitutionality and Continued Activism

The broader judicial push to rid the state of the practice included years of constitutional challenges filed by Louisiana defense attorneys and inmate counsels, repeated petitions to the US Supreme Court, and litigation by Richard Bourke, director of the Louisiana Capital Assistance Center. Bourke’s appeal in State v. Maxie (2018) was the first case to successfully convince a state court to declare non-unanimous juries unconstitutional. In April 2020 the US Supreme Court, which had been instrumental in maintaining the system, finally followed suit when it ruled non-unanimous juries unconstitutional in Ramos v. Louisiana (2020). Although decision did not include a mandate for retroactivity, the court decided against it in the following year when deciding Edwards v. Vannoy (2021). Thus Louisiana’s Jim Crow jury system, as it came to be known, disappeared. Yet well into the twenty-first century, hundreds of prisoners convicted by that system, the vast majority of them Black men, remain incarcerated because of it. Activists like Jamila Johnson, who helped lead the Unanimous Jury Coalition, continue to advocate tirelessly for the remaining victims of non-unanimous criminal jury verdicts. In 2021 Johnson led the effort to create a legislative task force charged with formulating a method to enable the judicial system and the Louisiana Department of Public Safety and Corrections to ensure equal application of the law to individuals in custody due to non-unanimous jury convictions. Though the practice has stopped, the fight is still ongoing.