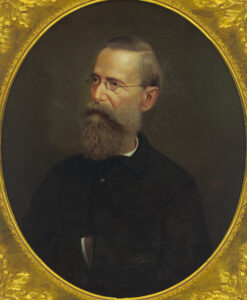

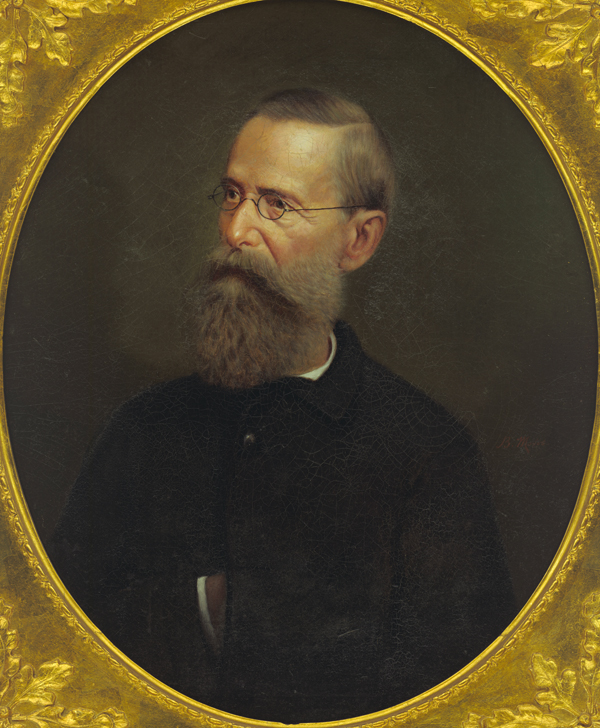

Andre Bienvenu Roman

Sugar planter and politician André Roman, a member of the Whig Party, served as governor of Louisiana from 1831 until 1835 and again from 1839 to 1843.

Courtesy of Louisiana State Museum

Governor Andre Bienvenu Roman. Kurz, K., Jr. (Artist)

S ugar planter and politician André Roman, a member of the Whig Party, served as governor of Louisiana from 1831 until 1835 and again from 1839 to 1843. Roman’s first term in office came during a period of tremendous political contentiousness—particularly between the state’s Creole population and recent Anglo-American immigrants—while his second came amidst economic turmoil brought on by the Panic of 1837. Though his first term is generally considered more successful, his service to the state is undeniable.

Born on March 5, 1795, in the Opelousas district of Spanish Louisiana, André Bienvenu Roman was the son of Jacques Etienne Roman and Marie Louise Patin Roman. Soon after his birth, Roman’s family moved to a sugar plantation located in what is now St. James Parish. After graduating from St. Mary’s College in Baltimore in 1815, Roman bought his own sugar plantation in St. James Parish. The next year he married Aimée Françoise Parent with whom he had eight children.

Roman was elected to the Louisiana House of Representatives in 1818 and served as speaker of the house from 1822 to 1826. From 1826 to 1828, he was a judge in St. James Parish before being reelected to the state house of representatives in 1828. In 1830 Roman was elected governor of Louisiana following a particularly combative race that, at various times, included French Creole Bernard de Marginy, former governors Jacque Villere and Arnaud Beauvais. and Anglo-Americans William S. Hamilton and David Randall. Around the time of the election, Kentucky statesman Henry Clay, a leader in the Whig movement, temporarily moved to New Orleans where he and his son-in-law, Martin Duralde, began planning Clay’s run for the presidency in 1832. Clay’s support proved crucial in Roman’s victory.

As governor, Roman worked to establish an innovative penitentiary system in Baton Rouge and increase state support for elementary and secondary education. He also advocated the establishment of Jefferson College in St. James Parish and Franklin College in New Orleans and worked to improve the state’s levees, roads, and bridges. During his tenure, the number of banks in Louisiana more than doubled and the Louisiana Agricultural Society was incorporated.

At the end of his first term, Roman ran for a seat in U.S. Senate but was defeated by Alexandere Mouton. In 1839 he won a second gubernatorial election amidst a climate of increasing economic turmoil. Much of Roman’s second term was spent trying to stabilize the state’s economy after the so-called Panic of 1837, caused—at least in part—by an overexpansion of banks. Toward this end, Roman helped bring about more restrictive banking regulations, culminating in the passage of the Bank Act of 1842.

After leaving the governor’s office, Roman served as a delegate to the state constitutional conventions of 1845 and 1852, as well as to state’s 1861 secession convention where he opposed secession. Despite this initial opposition, Roman eventually joined the Confederacy and was sent, along with John Forsyth and Martin J. Crawford, to seek a peaceful compromise with the United States. Their mission failed, however, when the US Secretary of State, William H. Seward, refused to meet with them.

The Civil War (1861-1865) financially ruined Roman as it did many other Louisianans. After the war Roman was appointed recorder of deeds and mortgages in New Orleans but died on January 26, 1866, before taking office. He is buried in the St. James Catholic Cemetery on the family plantation in St. James Parish.

Adapted from Joseph G. Tregle’s entry for the Dictionary of Louisiana Biography, a publication of the Louisiana Historical Association in cooperation with the Center for Louisiana Studies at the University of Louisiana, Lafayette.