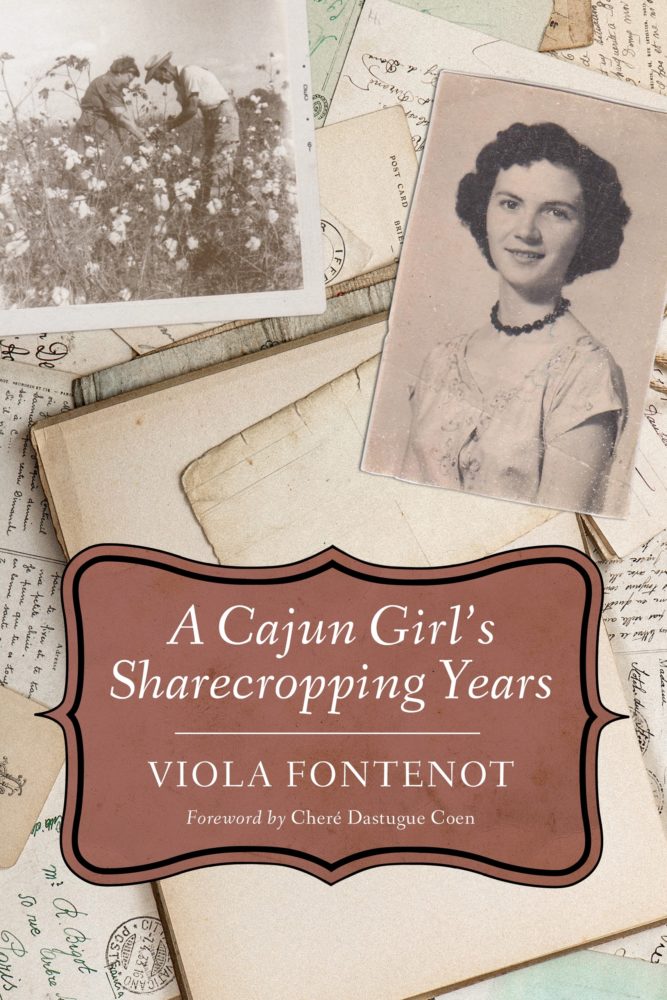

A Cajun Girl’s Sharecropping Years

A first-time writer pens a vivid portrait of her Acadiana childhood

Published: March 1, 2019

Last Updated: March 22, 2023

University Press of Mississippi

The 2019 Humanities book of the year is A Cajun Girl’s Sharecropping Years, a memoir published by the University Press of Mississippi of a rural Acadiana childhood in the ’30s and ’40s. Author Viola Fontenot described the work and her process in an email:

I grew up in the prairies near Richard and Church Point with my French-speaking sharecropper mom and dad, who would make a verbal barguine (bargain) with the landlord to provide farm labor for a one-third share of the profits from crops. Sans electricity or running water, life was tedious. ‘I will not speak French at school’ was my first-grade lesson; by third grade, my two younger sisters and I followed Mama and Daddy to work in the cotton fields. Education was my key out, and I graduated fifth in my high-school class with a Louisiana State University scholarship. Two weeks later, I married a Cajun boy in Eunice and went on to raise four children.

After I retired as an assistant vice president of a bank, I enrolled in the 2009–10 University of Louisiana at Lafayette life writing classes for seniors. My sharecropping stories were penned during those four semesters. The essays, intended for my children, formed the basis of my 2014–16 manuscript. To complete the work took me over two years of perseverance and divine alignments, writing four days a week. Getting published stretched two more years.

We are pleased to share selections from A Cajun Girl’s Sharecropping Years with 64 Parishes readers.

We spoke only French, the language of our ancestors, and lived a simple sharecropping life. Our three-room rustic house, without electricity, running water, or a bathroom, was located in the prairies of Acadia Parish near Church Point, stood near a bayou at the end of a rutted farm lane, and was isolated by tall thick woods. I was the eldest of five, the first of three children that were each born thirteen months apart. […]

Wearing used dresses and going barefoot or wearing my ugly high-top shoes contributed to my feelings of isolation and intimidation at school. I was shy and spoke only French. But speaking French on the school grounds was strictly forbidden. Trying to make myself understood was embarrassing. I felt belittled by the teacher’s disapproving frowns, stern looks, and squinting eyes. Her superior attitude undermined my self-esteem. In general, the school teachers’ attitude toward Cajun culture made me feel ashamed and second-rate, as if speaking French was a bad thing or a stigma. Although I wasn’t the only one who spoke French, each time I was caught speaking it, my teacher instructed me to stand in front of the whole class while she whacked my hands with a ruler or ordered me to write one hundred lines of “I will not speak French on the school grounds anymore.” Sometimes she assigned both punishments. It was meant to disgrace me! In spite of all my teachers’ efforts to exterminate my French language and my heritage, I soon figured out it was in my best interest to keep both French and English, one for school and one for home and family.

The naturally proud, stubborn, and clannish French-speaking Acadians resisted any attempts to become “Americanized” by the English-speaking community. “Les américains,” Daddy said, “want us to give up our language, our music, and our way of life.” He didn’t like les américains. And he wanted to be left alone to live his simple, uncomplicated life in harmony with the land, the endless wild woods, and the bayous.

It was 1948 or 1949, and the talk was going around! I was about twelve years old and in the sixth or seventh grade, when I heard that electricity was headed for south Louisiana. Towns, cities, and our schools had electricity, but no one wanted the expense of electrifying the rural areas. President Franklin D. Roosevelt created the Rural Electrification Administration (REA) in 1936 to bring electricity to farms and rural prairies by providing interest-free loans to co-ops, and local and state governments. Financed by REA loans, distribution cooperatives were formed to erect poles, string lines, and install transformers throughout those areas.

The South Louisiana Electric Membership Corporation (SLEMCO) was the co-op formed in south Louisiana that finally brought electricity to Acadia Parish. I well remember the event.

“I see them,” I hollered to my sisters, who were out of view.

“See what?” they called back.

“The men,” I said as I jumped up and down.

“What men?” they asked, looking around as they approached me.

“The ones with the electric poles!”

I waved in the direction of the men who were plodding through the fields and across our pasture toward our house, surveying and marking the spots with little red flags. They unloaded several big trucks of equipment and supplies along the way.

I was transfixed! For more than an hour, time stood still.

Leaning against an old fence post, spellbound, I gazed at the workers as they dug holes, erected poles, attached transformers, and strung heavy coiled wires down the mile or so to our house. At last the work was complete and a string of poles and power lines forever dotted the farms and pastures of Acadia Parish.

Finally, one of the SLEMCO crew wired our house on behalf of the landlord. Eager and excited with anticipation, I barely slept that night.

What an event! The next day, an electric cord about two feet long, with a light bulb at the end, hung down from the ceiling in each room of our house. Although I was accustomed to electricity at school, it was pretty heavy stuff to have it at home. Mama saved the kerosene lamps for an emergency, and with glee, I pulled the chain in our bedroom for a bright light, ready to read and study.

That year, after the harvested crops were sold, Daddy bought three things: a wringer washing machine, a large deep freezer, and unexpectedly, a battery-operated radio. The freezer doubled as a part-time refrigerator for milk and leftover foods as long as these were monitored and removed before they froze. The wringer washing machine was highly prized over the washboard laundry chores. And I, as did my sisters, loved the Saturday night “Grand Ole Opry.”

Fontenot children with Mama, circa 1949. Top, left to right: Betty (about 9 years old), Chere Alice (about 29), Viola (about 11); bottom: Lester (about 6), Myrtis (about 3), and Jeanette (about 10). Photo courtesy Viola Fontenot.

At the start of eighth grade, when I was fourteen years old, Daddy’s deficient work force of three young girls had become fast cotton pickers, and that year we finished picking all our own cotton early and started school on time. Anticipating the new school year, I longed for the treasures of books that challenged my brain, instead of the sharecropper’s work that overworked my body.

“Cotton Pickers for Hire, Cash Paid by Day or by Week,” said large signs posted at several neighboring farms. By word of mouth Daddy got the news. Just like that, he announced that he had hired himself out, along with Jeanette, Betty, and me. I was angry, but he kept talking.

“This money will buy you new clothes and shoes,” he promised.

The more cotton I picked, the more cash I would get, I thought as he went on. I actually believed that by “hiring out” I would earn money for myself. What a treat it would be to buy my own things with my own cash! Maybe being a cotton picker for hire would prove worthwhile. The next night, Mom and Dad hand-stitched patches over the rips and holes of our old picking sacks.

A wagon or a truck arrived at sunrise to pick us up. For a few more weeks, we dragged our sacks and picked cotton all day. Hired pickers were served lunch and icy water on the breaks. Once in a while the boss handed us cold soda pop. My favorite was cream soda. Ah, c’était bon, it was good!

There was much competition between me, Jeanette, and Betty. Under the hot sun, I used both hands and picked fast. At the end of each row, I watched intently as the boss weighed my sack on the large, freestanding balance scale, and I peeked over his shoulder at my daily running tab.

The pounds were tallied for each person at the end of the week, and everyone was paid cash on the spot. I don’t recall exactly what we were paid. Research with the Louisiana Department of Agriculture and Forestry indicated that hired cotton pickers were generally paid one cent per pound. A few landlords paid up to two cents per pound, according to verbal comments made at one of my area French Table meetings […] The amount of cotton a person picked in one day varied according to their experience, maturity, and speed. It could be as little as one hundred pounds, or as much as two or three hundred pounds per day.

Who among us had picked the most cotton?

In an interview with my sisters several years ago, Betty insisted that she was the best picker and averaged about one hundred twenty-five pounds per day. I absolutely have no such recollection! My sixteen-year-old memory believes we each picked ninety, maybe one hundred pounds per day. Certainly, my well-experienced Daddy picked over two hundred. That amounted to about $2.00 a day for him and $0.90 a day for each of his three girls ($2.70 total).

But who got the cash? Contrary to what I had hoped, I never got any. Not even one nickel was put in my tired, dirty hands, nor into my sisters’. What I do remember is that my hard-earned cash was paid to Daddy and stayed with Daddy. A few pieces of clothes and pairs of shoes were bought for us, but whether from our harvested crops or from our picking for hire, I never knew.

. . . During plowing, planting, and harvest season, it was Daddy’s morning routine for him to round up and harness the mules. I recall several disruptive mornings when the mules rebelled. It seemed that the moment Daddy reached out to catch the bridle, the mule jerked his head and ran away. Patiently, Daddy gave it one more try, to no avail. That’s when he called in his troupe of girls. He positioned us at strategic places and warned us to stand our ground and shoo the mules back toward the barnyard gate. But I was afraid of them—they were so large and I was so small—so when the mules got near me I, too, ran away.

Amid loud tonnerre mes chiens (“thunder of my dogs,” a French cursing metaphor) and shaking his head, Daddy waved his hands at us to round up the mules again and yelled, “Allons essayer une autre fois—let’s try it once more!”

I recall the frightening morning when Daddy got so mad at Jerry (the instigator) that after he caught him, he grabbed one of Jerry’s ears and bit it! You can be sure we all high-tailed it out of the barnyard! Eventually, Daddy settled and harnessed the mules and headed out for the field.

Cajun backyard wedding reception. Left to right: Nita Courville, Ernest Courville, Viola Fontenot Courville, Alice Doucet Fontenot. Lee and Alice Fontenot’s home, old Chataignier Road, Saint Landry Parish, Louisiana, June 1955. Photo courtesy Viola Fontenot.

On Good Friday, all spring cultivation and field work halted. Instead, Daddy went fishing. He returned with a big mess of catfish, and we enjoyed an early supper of courtbouillon and fish-fry with relaxed down time. Mama took count of our brown country eggs in anticipation of dyeing them the next day. Saturday morning, Mama fired up the potbellied stove as she gathered the things she used to dye our eggs. We did not have store-bought dye; instead, Mama slowly boiled our eggs in separate pots of water with natural ingredients for different colors.

For rich browns and tans, she cooked the eggs in thick layers of previously used coffee grounds, which she had saved for several weeks. For various shades of green, the eggs were simmered in leaves Daddy had cut from the catalpa tree, or catawba, as we commonly called it. Numerous shades of pink resulted when she boiled the eggs with beets. Carrots colored the boiled eggs orange. Eggs simmered in yellow onion skins and cabbage were pale shades of yellow. Those cooked with red cabbage were various shades of blue-green, and those cooked in red onion peels produced a rusty red color. Sometimes Mama rolled the hot plain boiled eggs in a shallow dish of blue laundry solution for pale blue hues. […]

Egg dying done, Mama made a fig and blackberry pie. Saturday evening, our baths and hair washings were done with great care. Even though we didn’t have new clothes, our dresses were freshly washed, starched, and ironed to look our best. All dressed up Sunday morning, bright and early, we were all giggles and full of anticipation as we climbed into the waiting wagon with our pies and colorful eggs on our way to Mom-Mom Doucet’s Easter feast.

A Cajun Girl’s Sharecropping Years is available from the University Press of Mississippi.

Viola Fontenot grew up a sharecropper’s daughter. She is a retired assistant vice president of Tri-Parish Bank. She contributed to Growing Up in South Louisiana and is currently working on a children’s book, Le Petit Chaoui du Grand Bois.

—

Celebrate Viola Fontenot and all of the 2019 Humanities Award winners on April 4 at the Bright Lights Awards Dinner in Lafayette. For more information and tickets, visit www.leh.org/brightlights.