Spring 2018

An Alarm of Riot

On November 23, 1887, mobs of white vigilantes gunned down unarmed black laborers and their families during a spree lasting more than two hours, throughout mostly black neighborhoods in the city of Thibodaux

Published: March 8, 2018

Last Updated: June 10, 2019

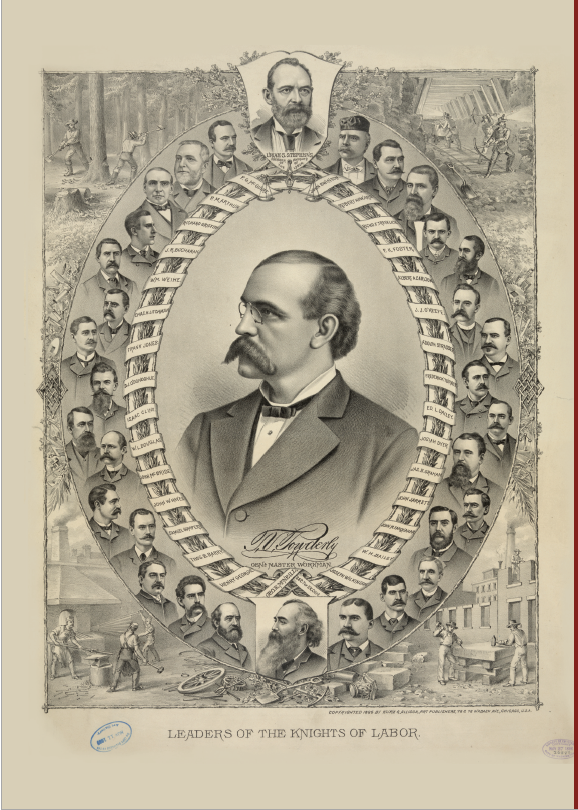

The Knights of Labor organized mostly black sugar cane workers to strike plantations.

Author’s Note: On November 23, 1887, mobs of white vigilantes gunned down unarmed black laborers and their families during a spree lasting more than two hours, throughout mostly black neighborhoods in the city of Thibodaux. The racial atrocity, largely a matter of hidden history for more than a century, grew from tensions over a strike of sugar cane workers in the parishes of Terrebonne and Lafourche. Frustrated by working conditions that changed little from slavery’s time, workers sought better pay. But most of all, they wanted elimination of scrip — the non-cash IOU payment that mostly was used to settle debt on plantation-owned stores where staples were sold.

Planters refused to negotiate with the Knights of Labor, a national group that organized locally in Terrebonne Parish, and true to their word, workers laid down their tools on October 29, 1887. The Louisiana State Militia was called in from New Orleans and evicted workers from plantation housing. Thousands of displaced workers from Houma, Schriever, Tigerville, and other communities trudged into Thibodaux, determined to force change.

But as time wore on, the tensions were transformed from a struggle over labor to one of race. Resentments that had simmered since the war and made bitter by the yoke of Reconstruction reached a boiling point among many whites. The tension was palpable when uniformed forces were withdrawn from Thibodaux. Whites whispered of a coming black uprising that never occurred. When entrance and exit from the town was blocked by armed civilian guards, blacks feared they were being hemmed in for slaughter.

Nobody knows, to this day, who shot and wounded a pair of volunteer guards at the edge of town in the pre-dawn of November 23. But the response is now a matter of historical record.

An estimated thirty to sixty black people were killed by the rampaging mobs, in some cases pulled out of their homes as they slept. The official record lists the names of eight victims.

Underscoring the nature of the violence was the sworn-to testament of the Reverend T. Jefferson Rhodes, pastor of Thibodaux’s Moses Baptist Church: “There were several companies of white men organized and they went around night and day shooting the colored men who took part in the strike.”

The City of Thibodaux and the Parish of Lafourche issued condemnations of the violence and acknowledgement of the deaths last year. A multi-racial committee is in the process of seeking to verify a mass grave where victims were believed buried by their killers.

The following excerpt from The Thibodaux Massacre: Racial Violence and the 1887 Sugar Cane Labor Strike paints a chilling picture of how harsh words, tension, rumors, and racism combined during a final, fateful week to touch off one of the most violent incidents in U.S. labor history, and one more shameful example of the post-Reconstruction racial violence that erupted in many other U.S. communities during the same era.

—-

The New Orleans newspapers continued reporting the escalating tensions, nonstop. One news report stated:“The town is full of idle negroes who each day become more and more audacious. The negroes who had left the plantations and taken refuge in the town of Thibodaux were being put up night and day to do acts of violence . . . a person could not go out into the streets without seeing congregations of negroes that wrought no good to the peace and order of the town. Some of the negroes boasted openly that if a fight was brought about they were fully prepared for it.”

Labor organizers continued preaching to workers that they could prevail in a prolonged standoff against the planters. The presence of dispossessed strikers no doubt appeared threatening to the whites, particularly those of the upper classes, the Lafourche planter elite. Written evidence suggests that what had begun as a labor movement was being seen—at least by planters and local government officials—as a burgeoning race war.

A keen observer and follower of the events was Mary Pugh, who had since the war’s end operated Dixie Plantation in Thibodaux—which was actually owned by Fannie Beattie, Judge Taylor Beattie’s wife and also Mary’s sister. Richard Pugh, her husband, died in 1885, and it is possible that after that time, she was living with friends or relatives in town. This is suggested because her letters to loved ones that include references to the strike are extremely detailed and could not have been garnered from the porches of the plantations with which she was associated.

Correspondence to her son Chuckie describes aspects of the strike consistent with press accounts of the time: “All last week the negroes became more and more violent in their manner and talk & openly bragged about how those at work were being shot at every night & said the Planters would be obliged to give in.”

On Sunday, November 20, Pugh attended St. John’s Episcopal Church with her son Allen and another family member. The service was sparsely peopled, with only ten congregants in the pews. The minister, Pugh related, expressed hope that the upcoming Thanksgiving Day service would go on as scheduled. As she walked out of the church, she saw that “over one hundred negroes were congregated just opposite & an another such group just across the canal where some negro was making them a speech to ‘burn the town.’”

A barrel maker identified in the newspapers as Rhody DeZauche had indeed given a speech that Sunday on the bayouside that was determined incendiary by the authorities. DeZauche was arrested, jailed, and charged with attempted murder. His words, the prosecutor said, posed a danger to life. After her visit to the church, Mary Pugh was horrified by other indications of burgeoning black “insolence.”

“I met negro men singly or two or three together with guns on their shoulders going down town and negro women telling them to ‘fight, yes, we’ll be there.’ You know what big mouths these Thib. negro women have—I wish they all had been shot off. They are at the bottom of more than half the devilment. Well I got home as fast as I could,” Mary Pugh wrote.

Several newspaper accounts noted the vociferous inclinations among black women: “The negro women of the town have been making threats to the effect that, if the white men resorted to arms they would burn the town and [end] the lives of the white women and children with their cane knives. It is no longer a question of capital against labor, but one of law-abiding citizens against assassins . . .”

Things changed for the worse, and citizens were afraid to go out upon the public highway for fear of being shot from ambush.

Unsubstantiated reports flew through Thibodaux streets that a black uprising was imminent. A cache of weapons, someone said, was being kept at locations on St. Charles Street, and an “alarm of riot” was sounded. One hundred armed white men converged on the back-of-town black neighborhood.

“You know what big mouths these Thib. negro women have – I wish they all had been shot off.”

“The report was circulated to the effect that two hundred armed colored men were massed for the purposes of mischief in the rear of town” is how the Thibodaux Sentinel framed the story. “The sheriff with an armed posse started out at once for the scene of the alleged trouble. But the matter turned out fortunately to be a false alarm.”

That Sunday night, as the last of the Shreveport guard prepared to leave, a mass meeting was held in Thibodaux’s town hall, chaired by Judge Beattie and attended by about three hundred “of the most prominent residents.” Silas Grisamore, who had chronicled the hardships of Camp Moore, initially presided, then asked Lieutenant Governor Knobloch to take over. A Picayune reporter was present and later wrote that those assembled represented “all trades and professions.”

A resolution was hammered out, presented by the boiler maker Ozeme Naquin, which stated that threats of violence received from the strikers and their sympathizers were “a disgrace to the parish and a reproach upon its good name for law and order.”

“This state of disorder shall and must cease,” the resolution continued. “We all, regardless of calling, avocation or pursuit, do now pledge ourselves and each other to use every means in our power to bring the guilty parties, and those who may have advised such lawlessness, to a speedy detection and punishment.”

The “guilt” referred to involved a wide range of offenses. The strike itself was regarded as lawless, as was the vagrancy of the evicted.

Nobody knew who had been doing the random shooting at sugar houses and replacement workers. But it was certainly a major concern. The resolution offered a reward of $250 “for the detection of parties guilty of those offenses.”

A core Committee on Peace and Order was selected. Sheriff Thibodaux offered to swear in thirty deputies, and patrols were promised to ride “day and night” to search out the guilty.

Armed vigilantes on horseback patrolled day and night, looking for anything that smacked of continued support for the strike and the potential for harm.

To state that the most prominent people in town were at the meeting was no exaggeration. In addition to Knobloch, Beattie, and Grisamore, the committee appointees were a who’s who of local commerce. Morvant, Lagarde, and Price were owners of successful plantations. Dr. Dansereau, a respected physician, was owner of one of the town’s finest homes, which stands to this day. Keefe was the owner and operator of Thibodaux’s celebrated foundry; Ozeme Naquin would move on from boilers to being a director of one of the town’s most successful banks. Andrew Price was an attorney and planter who would go on to be a congressman.

One of the committee’s first acts was to shut down the town entirely, requiring passes for people to enter or leave, amounting to martial law. Another was to seek out George and Henry Cox and jail them for inciting violence.

Letters from Mary Pugh and others express approval and support for the turn the town was taking. With the militia gone, Thibodaux would have to protect itself from the specter of marauding blacks. One of Mary Pugh’s letters reads almost as a portent: “They tried to [sic] hard to keep the peace they knew if things was once begun it would have to be well done, to end the trouble. I marveled at their patience.”

A young man of Pugh’s household named Jamie—descendants say they don’t know who he might have been—joined a local militia company headed by Lewis Guion, a local Civil War hero and former member of the Knights of the White Camellia. The cordoning of Thibodaux was done to contain blacks who were within and to prevent the entry of other people sympathetic to the strike. Some historians maintain that the order was perceived as a threat by strikers, who feared they would be penned in and attacked. Volunteer sentries were set up on the roads leading into town, their purpose to challenge travelers going in or out and to keep watch for the protection of life and property.

Pugh wrote that “the negroes became insolent and sneered at the soldiers and the citizens on the streets.”

“They proclaimed publicly that the white people were afraid to fire upon them and that they were prepared,” states a newspaper account. Whether they really were prepared—and the history as it developed shows they were not—the white citizens of Thibodaux were. Mary Pugh found her son Peter molding bullets at her home, and when she inquired as to why, he simply told her, “We might need them.”

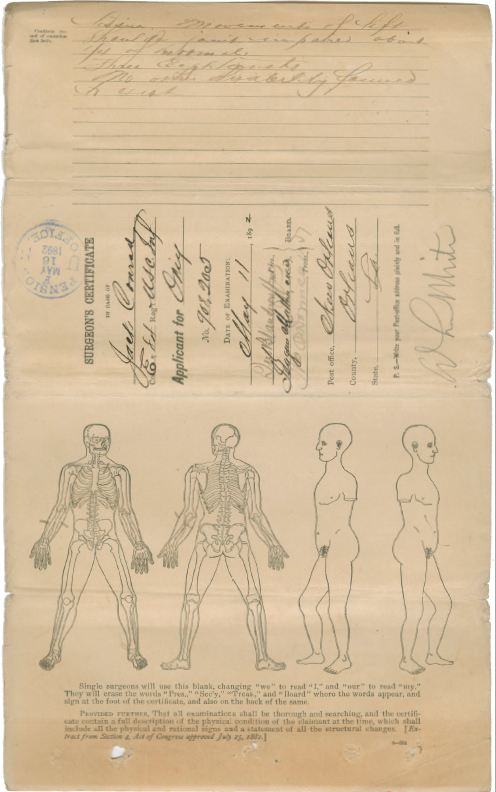

Thibodaux Massacre survivor Jack Conrad’s medical chart shows four gunshot wounds.

A notice, meanwhile, was sent out stating that the town would be patrolled, noting that “all are so wrought up at this moment the most trifling incident will bring on a terrible massacre.”

Armed vigilantes on horseback patrolled day and night, looking for anything that smacked of continued support for the strike and the potential for harm.

Mary Pugh wrote that “everyone was on the watch least [sic] they would attempt some violence . . . White men were armed & guarded day & night—of every street & inlet to the town.”

The patrollers—blacks called them “regulators”—made their purpose clear, sometimes with violence.

Peace and order enforcers, on Monday, stormed the St. Mary Street barroom of Henry Franklin, a black parish councilman and early supporter of the strike and a member of the Knights of Labor local committee that drafted the initial demand to the planters. Gunshots were fired into the saloon, and two black men were wounded. One of the wounded, William Watson, a twenty-three-year-old black laborer, ran out into the street but collapsed and died. The other, Morris Page, made his way home and survived. The assailants were not known to Franklin or other witnesses.

Despite the official sealing of the town, white men converged on Thibodaux from other parts of Lafourche to assist as rumors spread through the countryside. A “committee” of men from Terrebonne Parish made their way to Thibodaux as well.

Despite manpower shortages, local plantations tried to work their crops. A frost was feared and could spell ruin. Armed white men, as well as the recently departed militias, had become a common sight.

Mary Pugh’s son Peter was en route back home from his assigned volunteer post outside town, driven by his brother in a carriage. On the southeast corner of town, not too far from where Jack lived, Henry Molaison and John Gorman began their night watch.

The location Molaison and Gorrman manned was critical, near the point where St. Charles Street branches off of the main thoroughfare of the town, where ran the canal linking the bayou to Houma. It was also a gateway to the black section of Thibodaux, where the committee suspected strikers and their supporters were plotting “mischief” and “assassination.”

Gorman was a boiler maker by trade, an Irishman with bushy eyebrows who had sold Mary Pugh a horse at one point in time. Molaison was a clerk in his own father’s feed store. The night was a chilly one, and the pair stoked a bonfire to keep warm. At around 5:00 a.m. on Wednesday, November 23, Molaison and Gorman were having a “friendly discussion” with two other watchmen named Anslett and Gruneberg, about 250 yards from the still-burning bonfire, when a shot rang out.

“Gorman rolled over into the ditch nearby,” Molaison said. “I thought it was a pistol shot.”

Gorman was accompanied to his home by two of the civilian guard, and five minutes later, Molaison asked Anslett and Gruneberg to take his own place so he could go check on his friend.

“I had gone about 200 yards from Anslett when I was shot down,” Molaison said. A single bullet had entered the young feed clerk’s face just below the eye and then dropped out of his mouth.

“The news spread like wildfire and everyone was at arms,” wrote Anne “Nanny” Gay Price, the mistress of Acadia Plantation and mother of Andrew Price, in a letter describing the events in Thibodaux once the sun came up.

Mary Pugh’s segue into her account of what followed was chilling in its near-poetic tone: “And this opened the Ball.”

—-

John DeSantis is the senior staff writer at the Times of Houma. A recipient of numerous awards from the Louisiana Press Association, the Associated Press Managing Editors Association, and other news media organizations, he resides in Terrebonne Parish, Louisiana.

John DeSantis is the senior staff writer at the Times of Houma. A recipient of numerous awards from the Louisiana Press Association, the Associated Press Managing Editors Association, and other news media organizations, he resides in Terrebonne Parish, Louisiana.

Editor’s Note: The Thibodaux Massacre: Racial Violence and the 1887 Sugar Cane Labor Strike by John DeSantis for the 2018 Book of the Year, part of the Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities annual Humanities Award. To learn more, visit leh.org/humanities-awards.