Magazine

A Friendship Interrupted

New Orleans and Cuba enjoyed a strong commercial relationship prior to embargo

Published: June 1, 2017

Last Updated: May 13, 2019

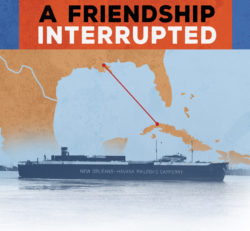

Courtesy of the Historic New Orleans Collection, Charles L. Franck Collection, 1979.325.6282

SS Sea Level of the West India Fruit & Steamship Company provided service between Louisiana and Havana from 1932 to 1953.

When Governor John Bel Edwards flew to Havana last October to talk business with Cuban officials, it was hard to believe a strict trade embargo still existed between Cuba and the United States. Flanked by about fifty port leaders from around Louisiana, Edwards signed a memorandum of understanding with Director General Manuel Fernandez Perez Guerra of Cuba’s National Port Administration, promising to share information and participate in joint efforts to promote trade between Louisiana and its island neighbor. The agreement was mostly ceremonial, of course—the United States government still prohibits almost all trade with Cuba, aside from humanitarian commodities like food and medicine. Lately, however, interest in ending the embargo has increased considerably, which Louisiana business and civic leaders have interpreted as a prime opportunity. As a result, state officials have worked closely with their Cuban counterparts to ensure that as soon as Congress lifts the trade embargo, Louisiana will be ready to take full advantage. As one state lawmaker put it after visiting Cuba for an agricultural trade mission last year, “We want to be the first in the gate.”

Before the embargo, Cuba had been Louisiana’s largest single foreign trading partner.

For the current generation of Louisiana port leaders, opening up trade with Cuba feels like an exciting new commercial frontier. From a historical perspective, however, it’s merely the renewal of a centuries-old relationship that was at its peak in the 1950s, until the Cuban Revolution broke out. Before the embargo, Cuba had been Louisiana’s largest single foreign trading partner. About a third of all exports leaving the Port of New Orleans were destined for Cuba, mainly flour, rice, and other foodstuffs. Likewise, New Orleans handled more than 1.2 million tons of Cuban imports, mostly unrefined sugar and molasses. More than six thousand Louisianans worked in industries directly tied to this lucrative commerce.

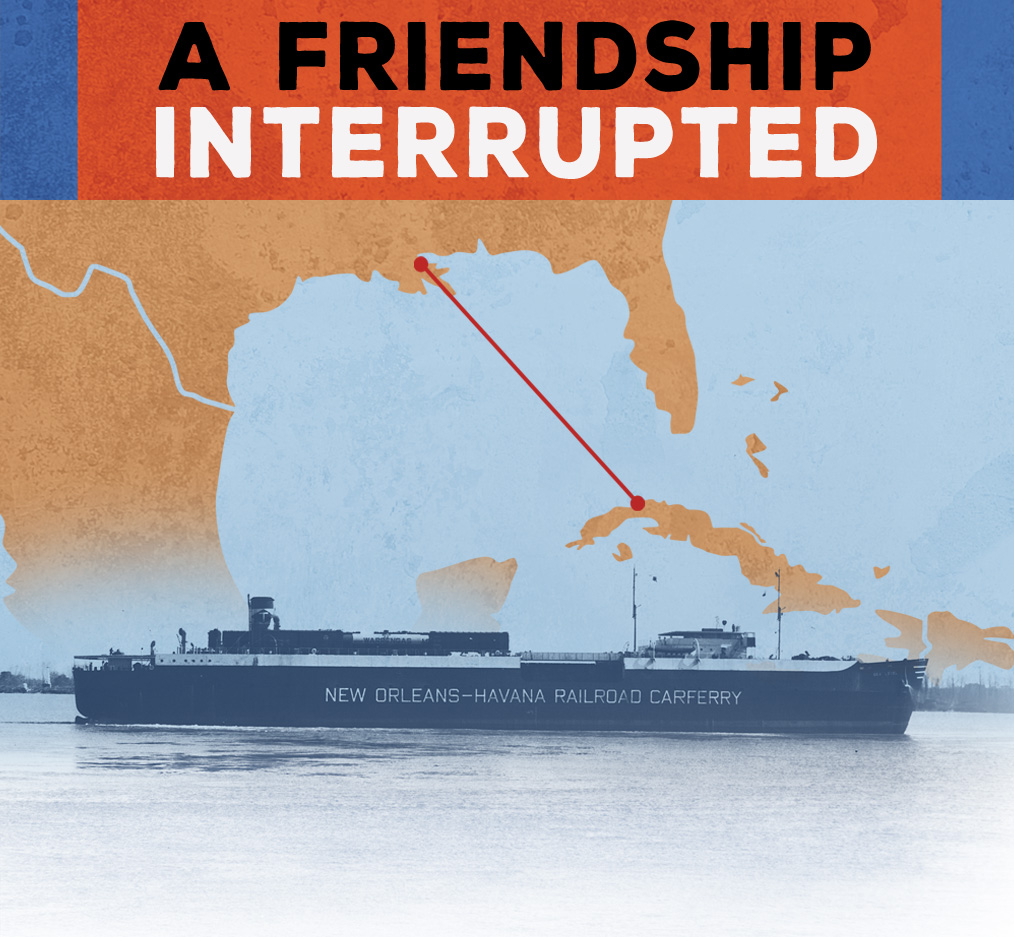

Fidel Castro in Washington, D.C., 1959. Courtesy of the Library of Congress

The numbers only tell half the story, however. A dynamic collaborative relationship between the business and civic leaders of New Orleans and Havana lay behind these impressive trade statistics. The two cities had been connected by commerce and migration for centuries, but the rapport became particularly strong between the end of World War II and the start of the Cuban Revolution. Importers, exporters, shippers, bankers, newspaper editors, mayors, and other leaders on both sides of the Gulf of Mexico saw the Havana–New Orleans axis as a crucial stimulant for growth in both places.

For the New Orleans business community, a strong relationship with Cuba helped support the city’s claim to be the nation’s “gateway to the Americas.” Trade experts had predicted that Latin America and the Caribbean would be especially valuable markets for trade and foreign investment while Europe was rebuilding after World War II. New Orleans’ business leaders aimed to maximize their share of the spoils by promoting the city as both geographically convenient for inter-American trade and uniquely appreciative of Latin American traditions and culture. “The people of Latin America look to New Orleans as an economic and cultural beachhead in the United States,” explained Mayor deLesseps S. “Chep” Morrison, a key architect of the city’s growing internationalist ethos. “We must encourage them to feel that way.”

Morrison and local trade promoters directed some of their best efforts at Havana in the late 1940s and 1950s. The mayor personally visited Cuba on several occasions in his official capacity, and Havana’s mayors reciprocated. When New Orleans first lobbied for permission from the Civil Aeronautics Board to offer international flights on a permanent basis, Havana was one of the destinations requested and ultimately received. Once the flights began, Mayor Morrison lost no time traveling to Cuba for a round of speeches hyping up New Orleans’ value as a trading partner and tourist destination for wealthy Cubans. In so doing, he aimed both to promote the city’s Latin-friendly image and to cut into the business of its rivals—especially Miami. “In the past,” Morrison said, “Miami has had all the breaks with its 90-minute air service to Havana. Now . . . we are ready to move in and contest Miami’s tourist and commercial advantages.”

Cuban Panorama was a celebratory exhibit of art and culture presented to the city of New Orleans by the Cuban Government in 1956. Courtesy of International Trade Mart

Although business was clearly at the center of the city’s overtures to Cuba, local leaders also took steps to make New Orleans seem more attuned to the island’s history and traditions. In 1950, city officials teamed up with the Chamber of Commerce and other trade promoters to stage an elaborate spectacle celebrating the centennial of the Cuban flag. Narciso Lόpez, a Venezuelan adventurer, reputedly designed the flag and had it made in New Orleans in 1850 before unsuccessfully attempting to liberate Cuba from the Spanish. New Orleans marked the hundredth anniversary with a parade of Cuban and American soldiers marching together through the streets to music from the Cuban Navy band. Similar honors accompanied the hundredth anniversary of the birth of Cuban patriot José Martí three years later. The City Council designated the day as “Martí Day” and hoisted the Cuban flag at City Hall following a ceremony in the mayor’s office. Both of these occasions, and many others, were accompanied by banquets, visits from distinguished Cubans, and plenty of speeches lauding the warm relationship New Orleans had with its island neighbor.

Cuban officials and business leaders were receptive to New Orleans’ campaign, mainly because it worked to their benefit. By 1950, trade between the United States and Cuba had become a billion-dollar enterprise. The island was importing more from the United States than it was exporting, however, which kept its leaders on a constant search for new markets for Cuban products, as well as more tourists to fill up Havana’s hotels and casinos. A strong relationship with New Orleans seemed likely to help Cuba achieve both objectives. In 1946, when New Orleans first established its International Trade Mart (which later became the New Orleans World Trade Center), Cuban business interests gave the project a great deal of support. Mark Trazivuk, a consultant who went abroad to promote the new center and find exhibitors to fill it, reported receiving free newspaper publicity and considerable help from the Cuban Chamber of Commerce and the National Association of Industrialists. In 1949, the Cuban government leased space in the mart to advertise the nation’s manufactured goods and promote tourism. Officials explained that they hoped to market more Cuban products to buyers in the Midwest, using New Orleans as a base. The government continued the strategy with a similar exhibit in 1956 titled “Cuban Panorama,” which attracted thousands of visitors from throughout the Mississippi Valley.

Councilman Victor Schiro receiving members of the Cuban delegation at City Hall during a trip to New Orleans in 1956. Courtesy of International Trade Mart

On the eve of the Cuban Revolution, the commercial ties binding New Orleans and Cuba could hardly have been stronger. Seven of the seventeen largest sugar companies in the United States had refineries located in and around New Orleans, all processing a significant amount of raw Cuban sugar. The Freeport Sulphur Company had also just announced plans to build a factory ten miles southeast of New Orleans to refine nickel and cobalt ores mined at Moa Bay, Cuba. Freeport officials predicted the plant would have the capacity to produce 50 million pounds of nickel and 4.4 million pounds of cobalt annually. This would make Louisiana the largest nickel-producing state in the United States and the new plant the largest cobalt refinery in the Western Hemisphere. Perhaps most appealing to local leaders, the project was poised to create hundreds of new jobs and pump millions of dollars into construction and related industries.

New Orleans’ persistent campaign to expand trade through goodwill and in-person promotion also appeared to be paying off. In 1957, Cuban president Fulgencio Batista told a group of visiting New Orleans businessmen that the city’s efforts epitomized what he saw as the “human side” of international trade—personal contact that led naturally to mutual trust. “Without that trust there can be no real friendship,” the president remarked. “And without friendship, foreign trade could hardly flourish.”

Morrison decided to try to win Castro over using the same personal diplomacy that had helped keep Cuba and New Orleans so close in previous years.

Batista and his New Orleanian guests had no way of knowing that the entire structure of New Orleans–Cuban commerce would be overturned in little more than a year. A growing army of revolutionaries led by Fidel Castro put increasing pressure on Batista’s regime, ultimately forcing the president and many of his allies into exile just before New Year’s Day, 1959. At first, New Orleans’ business and civic leaders were unsure how to respond. This was hardly the first abrupt Latin American transition of power they had seen in recent years, and Castro was not immediately identifiable as a communist. What did Castro want, and how would his government deal with foreign corporations and commerce? Even the United States government wasn’t entirely sure of the ideological underpinnings of Fidel Castro’s young regime, at least not in the first few months.

Mayor Morrison considered New Orleans’ relationship with Cuba too valuable to be left to chance. He decided to try to win Castro over using the same personal diplomacy that had helped keep Cuba and New Orleans so close in previous years. On at least two occasions in March and April 1959, the mayor sent telegrams to Castro, inviting him to visit the city. Castro declined both invitations on the pretext of a heavy schedule but asked to be invited again at a later date.

Mayor Morrison (far right) and Henry Sargent, president of the American & Foreign Power Company, admire pineapples at the Cuban Panorama exhibit. Courtesy of International Trade Mart

Morrison found another, grander opportunity to demonstrate New Orleans’ affinity for Cuba the following month. Under Batista’s regime, Havana’s traditional carnival celebration had dwindled and finally died out when the government forbade crowds of any size to assemble. Once Castro and President Manuel Urrutia took the helm, however, the festivities came roaring back with a five-week event dubbed the “Carnival de la Libertad,” or the Liberty Carnival. The Cuban government invited groups from around the Western Hemisphere to participate in the spectacle. Morrison seized this opportunity and assembled a 152-member delegation from New Orleans and the surrounding area to make a stunning contribution to the Havana event. The contingent included three floats from that year’s Rex parade (the pinnacle of New Orleans’ Mardi Gras celebration), ten majorettes, twelve Shriners, twelve traditional New Orleans street characters such as “the blackberry woman” and “the chimney sweep,” and a host of other performers. Three jazz bands played, including Famous Door’s Roy Liberto and orchestra, an act from the New Orleans musicians’ union, and The Last Straws.

The mayor reserved a powerful and symbolic presentation for himself and Victor Schiro, a member of the City Council and Morrison’s future successor. When the New Orleans contingent reached the presidential reviewing stand, Schiro appeared on horseback in the costumed likeness of Narciso Lόpez, the filibuster who had tried but failed to wrest Cuba from Spain in 1850. Schiro dismounted from his horse and solemnly carried a Cuban flag up to Mayor Morrison, who turned and presented it to President Urrutia. Speaking in Spanish, Morrison said, “Just as Lόpez brought the Cuban flag embroidered by ladies of New Orleans at the beginning of the nineteenth century on his liberating expedition to Cuba, so now, symbolically, the people of New Orleans again present the Cuban flag to the Cuban people.”

New Orleans’ performance in Havana’s Liberty Carnival embodied local business and civic leaders’ hopes that the commercial relationship between the city and Cuba would go on unchanged. Within a year, however, everything had changed. Castro’s government expropriated US businesses or made it prohibitively expensive to run them. Freeport Sulphur, for example, shut down its new nickel and cobalt factory near New Orleans when the Castro regime imposed a 25 percent tax on ore exports. Freight ships continued to ply the waters between Cuba and New Orleans for a while, but they stopped when cargoes dwindled down to nothing. Then came the embargo, first declared by the Eisenhower administration in late 1960, then strengthened by Congressional and presidential actions during John F. Kennedy’s term. New Orleans businessmen lamented the loss of trade, but they increasingly framed the situation within the context of the Cold War. Charles Nutter, director of New Orleans’ International House and one of the city’s foremost trade promoters, told one group that a popular revolt was the only hope for preventing Cuba from exporting its revolution to other parts of the Western Hemisphere. “It is possible,” he said, “that one half of Latin America could be Communist within five years, if the Red advance isn’t stopped.” Even Chep Morrison was forced to turn on Cuba, calling the Castro regime a threat to the entire inter-American system.

Now, over half a century later, the icy wall that has separated New Orleans and Cuba for so long appears to be thawing, slowly. Louisiana governor Kathleen Blanco started the process in 2005 by negotiating a contract in which the Castro regime agreed to purchase $15 million in rice, peppers, and other foodstuffs from the state’s producers. Also, since 2010 Louisiana poultry farmers have shipped more than 100,000 pounds of frozen product to Cuba under a special dispensation from the federal government. Federal regulators keep tight reins on these shipments, but Louisiana has managed to become the number one state in US exports to Cuba, to the tune of about $1.4 billion cumulatively.

Today, the future of the nascent rapprochement between Cuba and the U.S. remains uncertain. During his confirmation hearings in January 2017, Secretary of State Rex Tillerson criticized the Obama administration’s outreach to the island nation, arguing that the U.S. had failed to hold the Cuban government accountable for its legacy of human rights violations. As a candidate, President Trump threatened to close the U.S. embassy in Havana if the Castro regime did not meet his demands for “religious and political freedom for the Cuban people.” Nonetheless, Louisiana’s commercial leaders have committed to preparing for change. By exchanging visits with their Cuban counterparts and planning for the future, they are opening up possibilities for a productive new market once the embargo is lifted. In many ways, however, it’s only the latest phase in a relationship as old as Louisiana itself.

Joshua Goodman, PhD, is Teacher Programs and Curriculum Coordinator at The National World War II Museum in New Orleans.