Fall 2024

“A Game with Death”

The murder mystery novel that gripped Depression-era New Orleans

Published: September 1, 2024

Last Updated: December 1, 2024

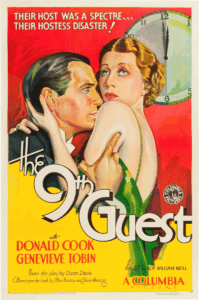

Columbia Pictures

Poster for The Ninth Guest, a 1934 film adaptation of The Invisible Host from Columbia Pictures.

As the Great Depression descended on New Orleans, a small-press murder mystery debut coauthored by a pair of newly married crime reporters became a surprising smash. Published by the Mystery League, Inc., in 1930, copies of Gwen Bristow and Bruce Manning’s The Invisible Host could be purchased from cigar stands and drugstores for just fifty cents, the perfect price for an era of empty pockets.

Set in a well-appointed art-deco penthouse of the fictional Bienville Building, Bristow and Manning’s premise is creepy, convoluted, and utterly outlandish. Eight guests receive identical telegrams from an anonymous host inviting them to the “most original party ever staged in New Orleans.” A motley assembly of minor acquaintances—a socialite, professor, financier, playwright, attorney, politician, painter, and actress—make up the guest list. Each guest hates the others. “Every one of us knows,” one guest deduces, “that there’s somebody . . . whom he most particularly wouldn’t be found dead with.”

As the web of rivals makes nice over cocktails, a voice “like a corpse talking” materializes on the radio’s airwaves. “I invite you to play a game with me,” the voice commands, “a game with death.” The penthouse, the incorporeal host explains, is barricaded and booby-trapped, set to eliminate the guests one by one, on the hour, unless they can outwit and identify their demented host.

As the guest list is whittled down—executed via poison, electric shock, gunshot—the survivors throw back drinks, point fingers, pair off, split up, and break down. The scene devolves into a Hobbesian house party.

You might forgive the authors for having murder on the brain. Originally from South Carolina, Gwen Bristow finished a single year at Columbia University’s Pulitzer School of Journalism before joining the Times-Picayune staff as a crime-beat reporter in 1925. “I covered holdups, murders, investigations of Huey Long,” she reminisced three decades later in the same paper, “got nearly shot during a jailbreak and roasted alive on a burning oil tanker, went out on prohibition raids, and got married.”

She likely met Bruce Manning, then a reporter for the Houston Press, while covering the sensational murder trial of Ada LeBoeuf and her lover, Thomas Dreher, for the slaying of LeBoeuf’s husband. The reporters married in January 1929, in the same St. Mary Parish courthouse where the convicted killers were sentenced to hang less than three weeks later.

Living at 627 Ursulines Avenue in New Orleans, the newlyweds found themselves besieged by a neighbor who blasted his radio at all hours of the night. This inspired a game—who could craft the perfect revenge killing?—which evolved into a novel originally titled The Penthouse Murders. Its sinister premise appealed to Owen Davis, a prolific playwright who won the 1923 Pulitzer Prize for Drama. He swiftly adapted the then-unreleased murder mystery into a short-lived Broadway production, retitled The Ninth Guest, that eventually opened in Chicago and New Orleans. “You may have seen a lot of mystery plays,” one critic gushed, “but if you like your deaths and murders in groups, you ‘ain’t seen nothin’ until you’ve sat through all three acts of The Ninth Guest. Boy, O’Boy, O’Boy, O’Boy! What a thriller!”

Finally published as The Invisible Host, the novel is prosaic, exposition heavy, and shockingly violent— all body count, little substance. Still, the book sold far better than Bristow and Manning expected. They quit their jobs—Manning had by then started reporting for the New Orleans States-Item—and relocated to a Mississippi Gulf Coast mansion where they entertained a steady flow of the southern literary crowd. They published three more locally set mysteries over the next two years: The Gutenberg Murders, Two and Two Make Twenty-Two, and, the best of the bunch, The Mardi Gras Murders.

Hollywood inevitably came calling, purchasing the rights to The Invisible Host, and Bristow and Manning moved out west, buying a home on Rodeo Drive in Beverly Hills. The film, released under the title The Ninth Guest by Columbia Pictures in 1934, was indistinguishable from most of the sex- and violence-tinged schlock that crowded pre-Code theaters (tagline: “Their Host Was a Spectre . . . Their Hostess Disaster!”). Manning parlayed the opportunity into steady work churning out B-movie scripts for the studio system. He didn’t win awards or much in the way of recognition, but for the next twenty-plus years he wrote dialogue for many stars of Hollywood’s Golden Age: Constance Bennett, Douglas Fairbanks, Claudette Colbert, and Bette Davis.

With Hollywood mostly off-limits to women writers, Bristow stuck with novels, trading murder mysteries for historical fiction. Several of her books, including her Plantation Trilogy (1937–1940) and Jubilee Trail (1950), became national bestsellers.

The Invisible Host, retitled The Ninth Guest in later editions, appeared destined to spend eternity in sidewalk budget bins, treasures unearthed by only the most hardcore of mystery fans. That is, until some clever sleuth—their name lost to history—hypothesized that Bristow and Manning’s story had been poached by the Queen of Crime herself, Agatha Christie, for her 1939 blockbuster, And Then There Were None, which was not only the most successful mystery novel of all time, but—with over a hundred million copies sold—one of the top-selling books ever published.

Though Christie partisans deny her familiarity with the book, play, or film, the parallels between the two narratives are undeniable. Let’s connect the plots, shall we? In And Then There Were None, an anonymous host invites eight guests to an isolated island. Once gathered, the host reveals their scheme—via phonograph! Each will be murdered one by one.

And Then There Were None is the better book—an undeniably frightening, mid-career triumph of a master operating at full capacity. But while The Invisible Host falls short, it remains an early and ingenious example of what genre enthusiasts call a closed-circle mystery, in which a finite set of characters must solve a puzzle within a confined space. Today the plot device is—ahem—inescapable, central to the conceit of countless films (e.g., the Knives Out franchise), in-person interactive games (see the recent rise of escape rooms), and even reality television (What lucky lady will go home with Joey? Tune in to The Bachelor.). The closed-circle trope is of course nothing new; Chekhov’s 1884 novel The Shooting Party perfected a proto-form that dates back, at least, to the Book of Genesis (spoiler alert: it was the serpent, in the Garden of Eden, with an apple).

Bristow and Manning’s The Invisible Host more than makes up for its mediocrity as a mystery novel with the mystery surrounding its long afterlife, a whodunit for the ages: Did the Queen of Crime commit one of the greatest literary crimes of all? Whether real or conjecture, the Christie connection has undoubtedly provided a boost to Bristow and Manning’s mystery oeuvre; their four early 1930s mysteries have been recently republished in handsome editions by the UK’s Dean Street Press.

Rien Fertel has been writing the Lost Lit column for over seven years. He is currently obsessed with Netflix’s closed-circle reality raunchfest Too Hot to Handle.