Always on the Threshold

“God, don’t let me die before I do something useful.”

Published: August 31, 2023

Last Updated: November 30, 2023

National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

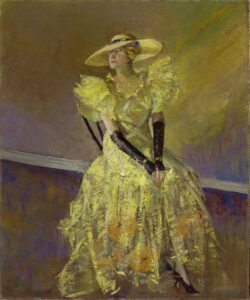

Laura Wheeler Waring, Portrait of Alice Moore Dunbar-Nelson, 1927. Oil on canvas.

With just a small handful of short stories, however, Dunbar-Nelson had an outsized effect. This biracial, bisexual woman publishing at the turn of the twentieth century foreshadowed the destiny of New Orleans literature more than any previous or contemporary author, and would later be claimed as a spiritual forebearer of the Harlem Renaissance. Writing at a time when most every other New Orleans author obstinately romanticized the city’s antebellum past, Dunbar-Nelson resolutely peered into the future, populating her city with people scrambling with anticipation to remove themselves from the stale archaisms of the 1800s, to greet whatever awaited them on the doorstep of a new era.

Scant early details remain about the woman born Alice Ruth Moore in New Orleans in 1875. Her father was white and physically absent from her life. Her mother, Patricia, recently freed by the Emancipation Proclamation, provided her with the rare opportunity of a middle-class education. Alice graduated from Straight University, which later became Dillard, and immediately found work as a public school teacher and journalist for The Women’s Era, the first newspaper published by and for African American women. Yet her multiracial ancestry allowed her to occasionally cross New Orleans’s nebulous color lines, a privilege that caused her dread. “I am,” she wrote in an unpublished essay, “white enough to pass for white, but with a darker family background, a real love for the mother race, and no desire to be numbered among the white race.”

Alice published her first book, Violets and Other Tales, a spare and uneven collection of prose fiction, verse, and poetic essays, in 1895, the year she turned twenty. The poetry skews Victorian—bland, romantic filigree. The essays—one on the capitalist undercurrents of schoolyard sports (“The football is money. See how the mass rushes after it!”), another a flâneuse’s tour of the French Quarter’s Exchange Alley—display a jejune, though perhaps accurate, critique of modern masculinity.

“God, don’t let me die before I do something useful.”

But it’s her fiction that truly soars. Her short stories feature New Orleanians caught between worlds: a schoolroom-trapped boy who longs for the “swamps and canals and commons and railroad sections, and its wondrous, crooked, tortuous streets.” A woman navigates life in and out and back into a doomed relationship. During Carnival, a mob of masked revelers bumps into a crowd of unmasked spectators and conscripts one unfortunate soul to join their untamed gang. For each character, crossing that threshold from one life to another brings not only disruption, but disaster and despair.

Alice’s own life would soon be disrupted in notable ways. After a lengthy epistolary romance, she moved to Washington, DC, and married Paul Laurence Dunbar, one of the first African American writers to achieve widespread fame. In 1899 she published The Goodness of St. Rocque, a collection of short fiction that included slightly altered versions of Violet’s three best tales. Once again, her characters unhappily find themselves trapped in fluid spaces and situations. Romances are constantly in flux. Beloved objects are lost and returned. My favorite tale, “Mr. Baptiste,” tells the story of an enigmatic, mild-mannered wharf rat who earns pennies selling half-spoilt fruit discards and unknowingly becomes ensnared between factions of a violent, racist longshoreman strike. Lives like Baptiste’s ebb and flow like the tides—today brings goodness, tomorrow you’re crashing against the rocks of hopelessness.

“Somehow when I start a story I always think of my folk characters as simple human beings,” she wrote her husband, “not as types of a race or an idea.” Alice’s characters inhabit what she called an “inconsistent miniature world.” They scan as liminal lives, never typecast but rather interpretable as Black or white, multi-generational Creole or recent émigré, Royal Street wealthy or “backatown” poor, conceivably queer. She understood that the best way to write about New Orleans and its people was to let the inconsistent, transitory nature of New Orleans seep into her writing: a city both old and new, permanent and ready to slip into the sea—in sum, a place always on the threshold of becoming something different.

Alice’s first marriage was defined by physical brutality and forced limits of confinement. She longed to burst free—to write, to more vocally champion civil rights, to pursue romances with women. After leaving Dunbar, Alice had several lesbian relationships and married twice more; she spent her final decades with the activist-poet Robert Nelson. But even in the wake of Dunbar’s death, she was frequently referred to as simply “Paul Laurence Dunbar’s widow.”

While on a cross-country speaking tour in early 1930, Dunbar-Nelson landed in New Orleans—likely her first time back home—just in time for Carnival. “It’s been such a lovely day that I can’t write about it,” she scribbled in her diary. “The old friends, the streets, the houses . . . just everything. I can’t describe—only feel. Every inch of ground seems sacred.”

But sorrow commingled with the holiday’s euphoria. “I wonder and wonder,” she wrote on Mardi Gras day. “Was I satisfied or disappointed?”

That pesky bug of career disappointment forever followed the author. “Damn bad luck I have with my pen,” she wrote a month after leaving New Orleans. “Some fate has decreed I shall never make money by it.” Publishing and public lecture opportunities soon dried up for Dunbar-Nelson, followed by a rapid decline in health. She would never produce another book in her lifetime, though her diaries—one of the earliest surviving daily journals written by a Black woman—would be published many decades later. She passed away in 1935, at the age of sixty, twenty years after begging God to grant her the ability to do something useful in this life.

This marks Rien Fertel’s twenty-fifth consecutive Lost Lit column. He wishes to thank his editors, especially Ann Glaviano, for their hard work and support.