Geographer's Space

A Mysterious Switch

An investigation of Louisiana’s change from counties to parishes

Published: March 1, 2017

Last Updated: June 30, 2021

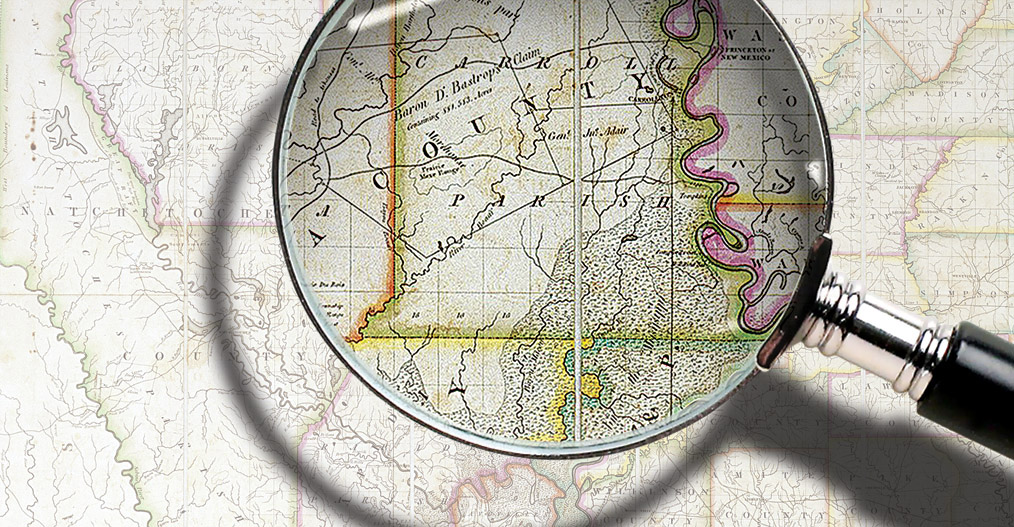

Courtesy of the Historic New Orleans Collection, 1959.197

An 1834 map showed both parish and county lines in Louisiana.

That Louisiana calls its political subdivisions “parishes” and not “counties” stands as a mark of the state’s cultural distinction, one learned by other Americans either in grade-school geography class or courtesy of a polite but firm correction from a proud Louisianan. So embedded is “parish” in the state’s spatial psyche that merely saying “counties” and “Louisiana” in the same sentence sounds dissonant.

In fact, for the first forty years of American dominion, the two terms, and their respective maps, coexisted as separate systems serving different purposes. The eventual adoption of “parish” may be viewed as a victory of localism over national assimilation, although politics and pragmatism also played roles. There’s also something of a mystery behind the change.

In colonial times, French and Spanish authorities felt no pressing need to break their territory into official sub-jurisdictions with rigid borders. Settlers were too few, and the terrain too vast or inaccessible, to necessitate precise delineation, and because colonials answered to an unelected monarchy, there was no need to draw up voting precincts or electoral districts.

Instead, people regionalized the colony based loosely on settlement cores and peripheries and the waterways among them. From east to west, there was La Mobile and Biloxi in present-day Alabama and Mississippi. Coming up the Mississippi brought you to le Detour aux Anglois (English Turn) and Nouvelle Orléans. Continuing upriver, Chapitoulas implied the banks by the present-day Jefferson/Orleans parish line; Cannes Brûlées meant Kenner; La Côte des Allemands referred to the German settlements across the river; Manchac was just south of present-day Baton Rouge; and Pointe Coupée covered the confluence of the Mississippi and Red rivers, which led respectively to the Natchez and Natchitoches regions. (Orthography, it should be noted, was as fluid as geography in this era.) Barataria, Lafourche, Attakapas, and Opelousas broadly implied the coastal marshes, east to west toward Spanish Mexico, whose border with French Louisiana was so vague that both empires tacitly viewed the area (Los Adaes) as “neutral ground.” Throughout the Louisiana colony, there simply weren’t enough settlers, nor hands-on government, to require clear, hardened jurisdictional boundaries.

The Catholic Church had different spatial exigencies, as clergy tended to their flock on a regular and more personal basis. Houses of worship had to be built; masses were celebrated weekly if not daily; sacraments were administered, children educated, tithes collected, and cemeteries maintained. All of these services required a more congealed sense of community geography, based around church buildings—although here too, ecclesiastic borders tended to be loosely drawn. In French, these units were called paroisses; in Spanish parroquias; and in English, parishes; and there were twenty-one such units throughout the Louisiana colony by the late 1700s. Because of the predomination of the Catholic Church, ecclesiastic parishes gained credibility and expediency as a way to organize Louisiana human geography. This would eventually prove useful to government.

After the Louisiana Purchase, representatives of the United States installed the apparatus of government they had honed elsewhere, and jurisdictional divisions topped the list of American administrative tools. In a section titled “Counties,” the Legislative Council in 1805 subdivided the Territory of Orleans “into twelve counties, to be called the counties of Orleans, German Coast, Acadia, Lafourche, Iberville, Pointe Coupée, Attakapas, Opelousas, Natchitcohes [sic], Rapides, Ouchitta [sic] and Concordia” and stipulated that many boundaries would follow the ecclesiastic “parishes of St. Charles…, of St. Bernard and St. Louis [meaning present-day St. Louis Cathedral]…of St. Charles and St. John,” etc. The resulting twelve counties thus reflected Catholic ecclesiastic parish lines or aggregations thereof, as well as colonial-era settlement concentrations—not to mention some completely invented straight lines.

Why, after forty years, was a standard nationwide concept abandoned in favor of something sui generis?

Despite their widely disparate sizes and populations, these twelve circa-1805 counties found their way into the State Constitution of 1812, which lumped them into districts for the election of senators, the apportionment of house members, and the creation of court districts. In other words, these were not really units of civil governance, as other states understood “counties,” but rather electoral and judicial districts. Nor were they purely ministerial: because they influenced who got elected where, counties were politically charged, and the Creole population—relative newcomers to the machinations of democracy—tended to view them askance, as a maneuver by which the incoming Americans might tilt representation in their favor. One Louisiana historian would later call the American-style counties “pernicious.”

For the purposes of civil governance, the Americans in 1807 realized that the twenty-one extant ecclesiastic units from late colonial times did a better job of regionalizing settlement patterns than their own twelve sprawling counties, and, after some adjustments, adapted them into nineteen official “parishes.” More were added as former Spanish West Florida and the old Neutral Ground by the Texas–Mexico border joined the state, and as sprawling prairie and piney woods parishes were broken into smaller ones. For decades to come, both counties and parishes coexisted, the former for electoral and judicial purposes, the later for civil governance dovetailing with religious congregational patterns. The dual systems were as confusing as their borders, which, in this era of weak central government, remained ambiguous—as did many of the parish seats, which might relocate when populations shifted or a courthouse burned.

What made the county/parish terminology additionally problematic was its dual misalignment with other American states, which used “districts” to mean what “counties” meant in Louisiana, and “counties” to mean what “parishes” meant here. Both units kept popping up in state legislation and constitutions from the 1810s to the early 1840s, giving them continued life in the legal lexicon as well as the vernacular.

But this being a mostly French-speaking Catholic state, at least in the south where the majority of the population lived, parishes were more familiar and more popular, and counties never really caught on. The average Louisianan in this era spoke the language of parishes, despite that counties remained on the books and on the maps.

What killed counties in Louisiana was the Constitution of 1845. When delegates convened in Jackson and New Orleans between August 1844 and May 1845 to discuss the new constitution, they spoke plenty of both parishes and counties. To wit, the word “county” or “counties” appears nineteen times in the published Proceedings of the Constitutional Convention. But the context of some usages—for example, “county or district” and “county or parish”—suggests the delegates were grappling with these terms.

Then something changed. When the final constitution was ratified on November 5, 1845, the word “parish” could be found roughly a hundred times. But, remarkably, “county” and “counties” had completely disappeared. Electoral representation would now be apportioned by parish units and their populations, as well as by new senatorial districts. The Constitution of 1845 ended all official talk of counties and permanently entrenched parishes in the map and political culture of Louisiana.

Why, after forty years, was a standard nationwide concept abandoned in favor of something sui generis? No explanation was provided by delegates for the omission, and it’s tempting today to view our parishes as a triumph of localism and traditionalism over external agents of change. Consider the circumstances: this era saw the peak of the political wrangling between the older, locally born Catholic Francophones (Creoles, including in this context Cajuns) and the recently arrived English-speaking, mostly Protestant Anglo-Americans. Debates arose constantly over matters such as the French versus English language, Roman Civil Law versus English Common Law, Creole versus Anglo voter apportionments, and other flashpoints. Counties were an American import, and they symbolized the geography of American political power, whereas paroisses, parroquias, and parishes spoke of all things Creole: Catholicism, the ancien régime, the Creole sense of place, the Gallic parlance. The excising of counties may have represented an Anglo concession, or a Creole pushback, to finally eradicate an unloved term already eschewed by the populace.

Pragmatism also played a role. To this point, Vidalia historian Robert Dabney Calhoun, interviewed by the New Orleans Times-Picayune in 1937, explained the last time “county” came up in state law. An Act of December 16, 1824, stipulated that “the sheriff of the Parish of St. John the Baptist shall be ex-officio sheriff of the county of German Coast, and that in the future only one sheriff shall be appointed for said county.” The act illustrated how redundant jurisdictions could lead to waste and confusion. When in 1843 that same sheriff attempted to pay his state taxes using his $290 compensation, which had been issued as notes by a now-defunct bank and were therefore worthless, the state had to pass a bill to authorize the transfer “from the sheriff of the German Coast county.” That was the last time “county” appeared in state law, and the uncertainty of the sheriff’s vague parish/county double duty may have set off a conversation among legislators and led to the pointed exclusion of “county” from the 1845 Constitution.

“There never was a legislative act formally abolishing the old counties; nor was there such abolition by the new constitution,” explained Calhoun. “The old counties had died years before from a pernicious political anemia,” he wrote, in reference to how the original counties swayed electoral representation. “The old counties,” he concluded, “may be likened to a row of old picture frames which were allowed to hang on the wall for many years after the portraits had been removed.”

But what precisely changed over the course of 1844–1845, when “county” came up repeatedly at the Constitution Convention but then utterly disappeared in the final Constitution, never to resurface?

So far as I can determine, it’s a mystery.

Richard Campanella, a geographer with the Tulane School of Architecture, is the author of Bienville’s Dilemma, Geographies of New Orleans, Bourbon Street: A History, Lincoln in New Orleans and other books. He may be reached through richcampanella.com, [email protected]; or @nolacampanella on Twitter.