Louisiana State Museum

A Spanish Father and a Creole Daughter’s Monumental Legacies in New Orleans

An exhibition at the Cabildo looks at the Pontalbas’ architectural influence

Published: March 1, 2019

Last Updated: May 31, 2019

The Pontalba Family. Conservation courtesy of The Historic New Orleans Collection.

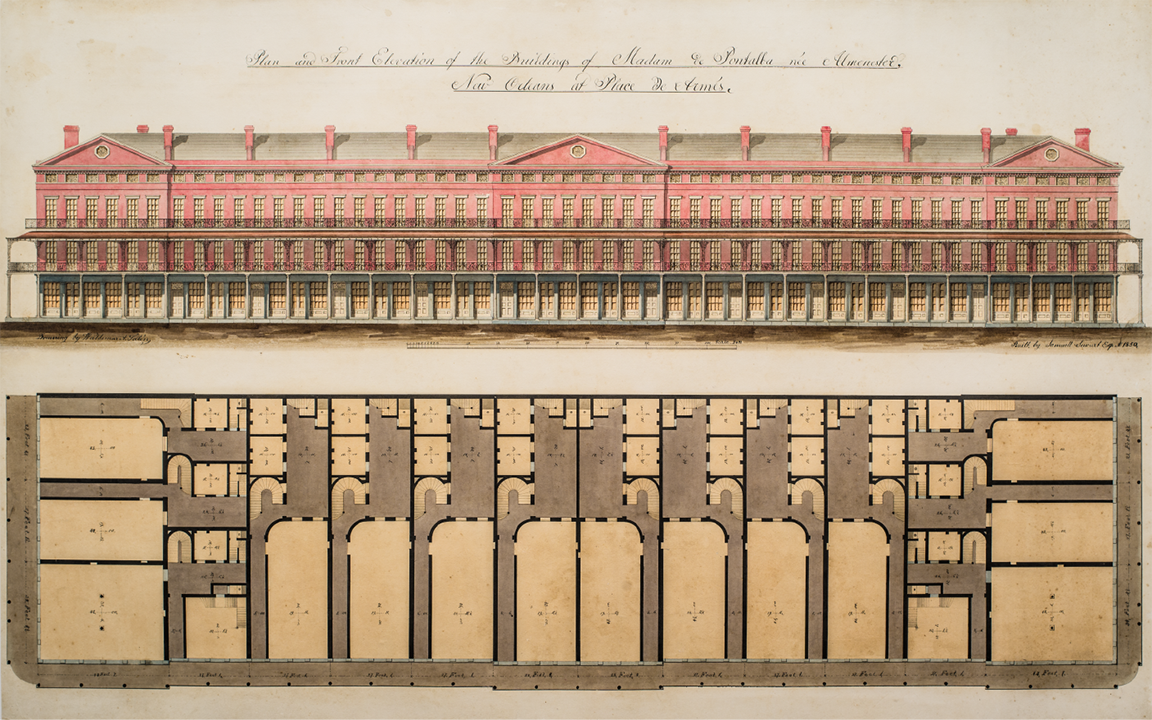

The sixteen-townhouse Upper and Lower Pontalba Buildings of 1849–1851 are late Greek Revival with Italianate verandas. This rendering, recently discovered in the Pontalba family holdings in France, is signed by builder Samuel Stewart and his draftsman, Waldemar Appolonius Talen, but no architect.

Don Andrés Almonester donated a new St. Louis Church after the fire of 1788. He also advanced the funds and selected the architect for the Spanish Cabildo, or city hall, and its twin, the Presbytère. Fifty years later, his daughter built the matching Pontalba Buildings on the land she inherited from her parents. Her two palatial buildings, with sixteen townhouses each, confirmed the fashion for cast-iron verandas, which became the architectural signature of New Orleans.

Waldemar Appolonius Talen designed the cast-iron elements that incorporate the AP (Almonester-Pontalba) monogram. The James L. Jackson, Brother & Co., Foundry in New York City manufactured the lacy ironwork. Photo by Richard Sexton.

The Pontalba Buildings have often been credited to New Orleans architects James Gallier Sr. and Henry Howard, but the reality is murkier. The baroness rejected James Gallier Sr.’s design, but she recycled his floor plans. She turned to architect Henry Howard, who quoted a fee of five hundred dollars. Howard testified in an 1851 court case, Stewart v. Pontalba, that the baroness claimed “that she was a good architect herself and said she built a great deal in France.” Howard indicated that the baroness had brought plans with her from New York. (Those drawings have not turned up in any archive.) He also testified that his designs were “somewhat different [than] the present design of the Buildings,” but there’s no testimony on how they differed. She paid him a $120 drafting fee to sketch what may have been primarily her own design. After providing the sketch, Howard dropped the project. It fell to New Orleans builder Samuel Stewart to make the working drawings and adjust the buildings to the site’s thirteen-inch downward slope from Decatur to Chartres Streets. The baroness’s contract with Stewart appended Gallier’s building specifications but crossed out his name.

Howard claimed authorship of the Pontalba Buildings in his 1872 autobiography, but historian Christina Vella, author of Intimate Enemies: The Two Worlds of Baroness de Pontalba, concludes, “That claim is not borne out by any document concerning the construction of the Pontalbas.” We are left with several mysteries. Who was the architect in New York? What, exactly, did Henry Howard contribute to the design? And what was the baroness’s role in her landmark buildings’ design?

The Baroness de Pontalba and the Rise of Jackson Square is on view at the Louisiana State Museum’s Cabildo through October 13, 2019.