Pontalba Buildings

Baroness Pontalba's buildings on Jackson Square changed the haphazard design into a viable public area.

Courtesy of Louisiana State Museum

Lower Pontalba Building. Johnston, Frances Benjamin (Photographer)

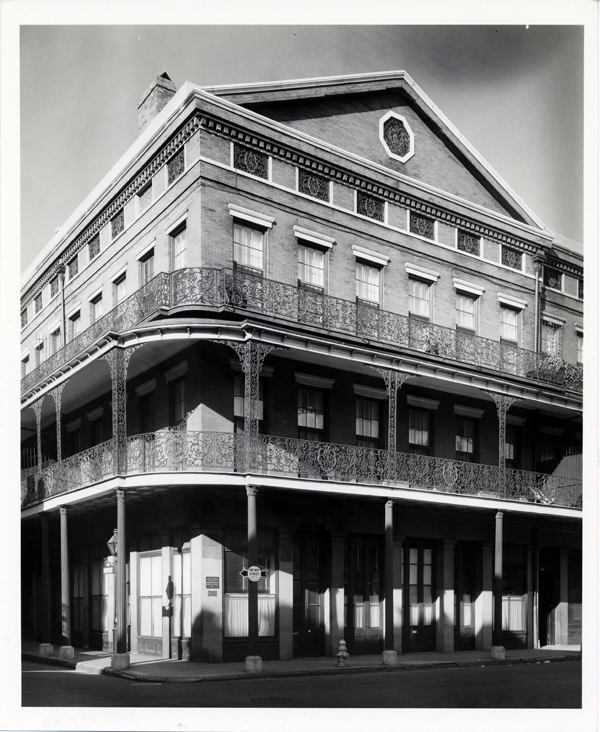

Twin block-long, red brick structures, generally referred to as the Upper and Lower Pontalba Buildings, face Jackson Square, lining St. Peter and St. Ann Streets. Constructed between 1849 and 1851, each building features sixteen elegant townhouses on the upper floors and separate commercial spaces on the ground floors. While the pedimented central and end pavilions bestow the buildings with an architectural grandeur, the delicate ornamental cast iron work—in an intricate, lacy pattern—evokes a mood of Parisian-like gaiety. Built at the behest of Micaëla Almonester de Pontalba, these monumental landmarks transformed a haphazardly developed area into an integrated, sophisticated urban space. The Pontalbas remain today as the lasting contribution of the Baroness Pontalba to the architectural landscape of the French Quarter.

The Site

On their 1721 plan of New Orleans, French military engineers Pierre Le Blond de la Tour and Adrien de Pauger designated the site as the center of the settlement’s public, religious, and governmental activities, with buildings on three sides and open to the Mississippi River on the fourth side. Constructed poorly for the southern Louisiana terrain, the early French colonial structures flanking the square survived for only a short time. By 1759, the older buildings had collapsed or were devastated by hurricanes, and the future site of the Pontalba Buildings remained vacant through the remaining years of French rule. Subsequently, Spanish governor Don Alessandro O’Reilly gave the land to the city in name of King Charles III. Between 1777 and 1782, Don Andres Almonester y Roxas, Baroness Pontalba’s father, purchased the land piecemeal.

Almonester built his own home at the corner of St. Peter and Decatur and a number of rental houses nearby; all escaped damage during the fires of 1788 and 1794. In the early 1800s, a few years after Almonester’s death, his widow rebuilt her properties on the square to conform to the building code regulations passed after the late-eighteenth-century fires, including her palatial home designed in 1811 by French-born architects Arsène Lacarrière Latour and Hyacinthe Laclotte. When Micaëla married Joseph Xavier Célestin Delfau de Pontalba in 1811, however, both mother and daughter moved to France. The French Quarter home was leased to Bernard Tremoulet as a hotel. During his visit to the city in 1819, noted architect Benjamin H. B. Latrobe sketched the building admiringly; his impression of the other buildings on the square, however, was not so favorable. As quoted in Baroness Pontalba’s Buildings: Their Site and the Remarkable Woman Who Built Them, Latrobe commented “the west side of the square and the whole of the east side is built up on very mean stores covered with most villainous roofs of tile, partly white, partly red and black, with narrow galleries in the second stories, the posts of which are mere unpainted sticks…. Nothing can have a meaner, dirtier and ill-formed effect that these buildings.”

Meanwhile, in France, the future Baroness became familiar with such grand Parisian architectural ensembles as the Palais Royale and the Place des Vosges. She envisioned adding continuous arches in front of her buildings on the square, mirroring those of the Cabildo and Presbytere. Estranged from her husband, Micaëla returned to New Orleans for a visit in 1831, where she began planning her grand project. As described in L’Abeille de la Nouvelle Orleans, Pontalba intended to construct “blocks of buildings that will bear comparison with any in the country and challenge rivalry from abroad.” Though legal and financial battles with her estranged husband delayed her plans, Pontalba resumed her New Orleans project in the late 1840s. Fleeing Europe during the Revolution of 1848, Micaëla arrived for her second and last visit to New Orleans and launched her building scheme.

Baroness Pontalba and Her Buildings

Her first plans called for addition of a two-story arcade in front of the old buildings, requiring the First Municipality’s permission for use of the public space. Eventually, however, the older structures were torn down and the Upper and Lower Pontalba Buildings constructed on opposite sides of the square. The design represented the collaboration of several talented builders and designers. Well-known New Orleans architect James Gallier, Sr., completed a series of preliminary drawings and specifications, which were actually attached to the 1849 building contract for the St. Peter townhouses. It was Henry Howard, however, who executed the final plans and claimed the design in his autobiographical sketch. Builder Samuel Stewart persevered throughout the entire project. Then, of course, there was the baroness herself, who, according to an eyewitness, actually donned men’s pantaloons to ascend ladders and, in effect, to act as the supervising architect.

The Pontalba Buildings’ striking cast iron verandas began the vogue for iron galleries in New Orleans. After completion of the Upper Pontalba in the fall of 1850, the baroness and two of her three sons moved into #5, today 508 St. Peter. The talented youngest son, Gaston, made a series of sketches of the Quarter during his visit between 1848 and 1851, now archived in the Louisiana State Museum. He also may have designed the “AP” monograph adorning the buildings’ cast iron verandas. In April 1851, the baroness left New Orleans with her two sons and never returned.

Baroness Pontalba’s grand project acted as catalyst for other municipal improvements on the square. In the late 1840s, before construction of the row houses had even begun, the First Municipality’s city council voted to add a mansard roof, popular in French architecture, and cupola to its city hall, the Cabildo. The wardens of St. Louis Cathedral followed suit and added a similar roof and cupola to the Presbytere. In 1850, the old Spanish cathedral was practically demolished and rebuilt according to the design of French architect J. N. B. DePouilly. In the 1850s, the old square itself was targeted for beautification. These efforts reflected, at least in part, an ongoing competition between New Orleans’ First Municipality, populated mostly by Creoles, and the Anglo-Americans, who lived primarily in the Second Municipality.

The Decline and Rescue of the Pontalba Buildings

The Pontalba Buildings attracted desirable, affluent tenants for only about a decade. By 1866, the Civil War had obliterated the prosperity of antebellum New Orleans, hitting the French Quarter especially hard. Immigrant laborers crowded into the neighborhood, often bringing large families, cats, pigs, and perhaps a cow or two. In reaction, Creole families scattered out along the Esplanade Ridge and even into the Americanized uptown suburbs. “A pall of poverty and decay hung over the old streets and houses,” preservationist Martha Gilmore Robinson recalled, and “tattered clothes fluttered from the iron balconies of the once proudly fashionable Pontalba buildings.” After the death of the baroness in 1874, her heirs took no interest in the New Orleans properties, and the buildings fell into disrepair.

Soon after World War I, however, a rekindled interest in the Quarter precipitated a cultural renaissance. In 1919, Le Petit Théâtre du Vieux Carré moved to the second floor of the Lower Pontalba at the corner of St. Ann and Decatur, where they remained until 1922. When the Pontalba family decided to sell off the property in 1920, New Orleans philanthropist William Ratcliffe Irby bought the Lower Pontalba, which he bequeathed to the Louisiana State Museum, which maintains control today. Alfred Danzinger, Jules D. Dreyfous, and William Runkel acquired the Upper Pontalba. In 1930, they sold the property to the Pontalba Building Museum Association, which in turn transferred the buildings to the City of New Orleans. The Upper Pontalba Building Commission, a city agency, still manages the property. During the 1930s, the Works Progress Administration provided extensive funding for renovation to both the Upper and Lower Buildings. In the past thirty years, both buildings have undergone several controversial renovations, while continuing to anchor Jackson Square with their stately presence.