A Virtuoso from Vidalia

Gray Montgomery played it all

Published: February 28, 2022

Last Updated: May 31, 2022

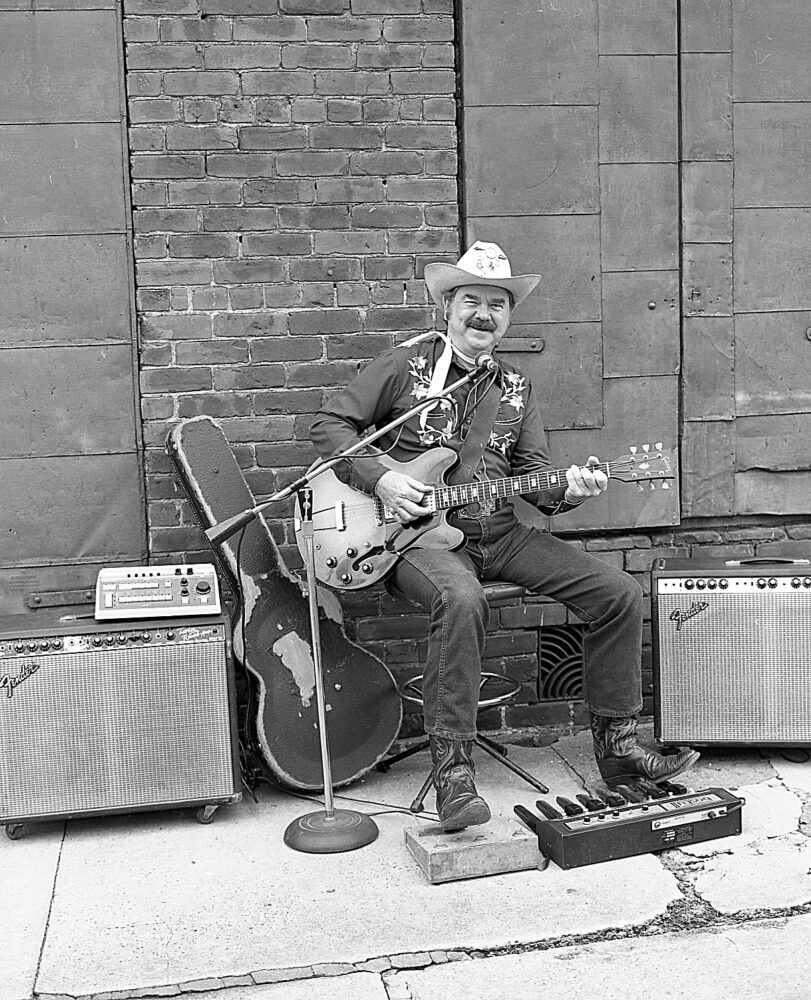

Photo by Tim McCary

Montgomery busking in downtown Natchez, 1990.

Montgomery’s repertoire included many styles of country, such as jazz-influenced western swing and the smooth “Nashville sound” typified by Chet Atkins; the African American blues tradition, for which the environs of Vidalia, Louisiana, and Natchez, Mississippi, have long been a hotbed; rockabilly, in the tradition of Jerry Lee Lewis, from nearby Ferriday, Louisiana; early rock, by such seminal songwriters and guitar stylists as Chuck Berry; miscellaneous pop songs; sophisticated “dinner music,” to enhance the mood at swanky eateries; the fleet-fingered ’40s fad typified by Arthur “Guitar Boogie” Smith; the subset of ’60s rock known as surf music; sentimental songs from the nineteenth-century parlor-music tradition; mildly risqué comedic numbers; and much more.

Montgomery was not merely an expert guitarist; although he performed solo, in effect he led a five-piece group. “I stomp my bass notes,” he explained during our interview. Montgomery played a pedal bass which resembled oversized piano keys, more typically utilized by jazz and gospel-music organists. Given the intricacy of his guitar work, this added foot action was no small act of coordination. He played harmonica, too, accessing that instrument with a contraption worn around his neck. And while Montgomery preferred to work with live drummers, the harsh economics of the music business dictated that he often used an electronic drum machine. On top of all this, Montgomery sang with a seemingly effortless, laid-back feel that was anchored in rhythmic precision. It was no exaggeration, therefore, that Gray Montgomery’s business card bore the slogan “one man band.”

Montgomery was born in 1927 in Parhams in rural Catahoula Parish. As a child his family moved to Vidalia, where music beckoned during his teen years. “I took up the guitar,” he told me, “when a kid who played real good moved into the neighborhood and all the girls went crazy over him. I got me a fourteen-dollar guitar, started rapping on it, and learned to play. And it worked—directly, those girls were going crazy over me, too!” By the early 1950s, Montgomery was playing in a wide regional radius, including a stint at a nightclub in neighboring Natchez, in a band where the drum chair was held down by a teenaged Jerry Lee Lewis. “We’d play everything: rockabilly, country, waltzes, blues. We’d mix it up good and try to keep everyone happy. But Jerry Lee would get mad real quick. Somebody’d make a request, and he’d say ‘we don’t play that kind of damn song around here!’”

In addition to this band, Montgomery worked with a renowned African American blues harmonica player who recorded under the name Papa Lightfoot but was known around Natchez as Papa George. (Lightfoot’s raucous version of “When the Saints Go Marching In,” which can be heard on various music websites, is highly recommended.) Interracial public performances were often banned during this era of strict segregation, but Lightfoot and Montgomery played together often nonetheless, “with no problem, either way,” Montgomery recalled. “The most fun we had,” he added, “was at Black clubs.” Montgomery also traveled for a time with Lash LaRue, a country artist who was best known for starring in low-budget cowboy films, armed with a bullwhip—hence his moniker. On the club circuit, LaRue expertly performed pop-the-whip routines that would almost certainly be illegal today because of liability issues. “He could pop a piece of paper out of a little girl’s mouth, and pop that paper in two. But that got old, and I wasn’t making enough money to pay my bills.”

Mechanically inclined, Montgomery instead found steady work repairing a wide variety of electronic devices. (Years later, Montgomery’s obituary would boast that “he could fix anything from an oil well blowout to a jukebox.”) Montgomery played where and when he wanted, instead of depending on music for his livelihood. He also recorded, sporadically; today, Montgomery’s record “Right Now”—released in 1962 as a single by the Natchez-based Beagle label—fetches more than five hundred dollars as a rare collectible. (This song, too, can be heard online.) After my chance meeting with Montgomery in 1989, his performance circle expanded to include appearances at Jazz Fest in New Orleans and at the Louisiana Folklife Festival, held in a different location every year. Montgomery hired me to play drums with him on occasion, and one of my fondest musical memories is performing the surf classic “Wipe Out”—a showcase song for drummers—that he spontaneously decided to play while onstage, with no advance notice.

At that time Montgomery was in his early sixties and absolutely, almost palpably, content. He had no regrets about passing on the pursuit of a full-time musical career—even though he could have amply held his own at the highest career levels. It is easy to picture Montgomery, for example, as a regular featured performer on the Grand Ole Opry.

“I did tour a few times,” he recalled, “but I didn’t like it to where I’d take a lot of punishment to do it, running after something that might not be there. I had a pretty good little old job, in Vidalia, and I didn’t want to turn that loose. And besides, I got married and had four daughters. I still like to play, and if nothing big comes along I’ll still be happy. Right around in here I got a lot of friends and they like to hear me play, and as long as somebody wants to hear you, it doesn’t matter if it’s millions or a few hundred.”

“I believe in living as happy as you can,” he concluded—“and if you’re gettin’ by pretty good, don’t jump out on a limb.”

Ben Sandmel is a New Orleans–based writer, folklorist, and producer. The former drummer for the Grammy-nominated Cajun/country band The Hackberry Ramblers, Sandmel is also the author of Ernie K-Doe: The R&B Emperor of New Orleans. In May 2018, the LEH honored Sandmel with an award for his Lifetime Contributions to the Humanities. In August 2021, Sandmel graduated from Tulane University with an MA in musicology.

Sound Advice is funded in part by a grant from the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Foundation.