Fall 2024

Abdalla’s: A Store for All Seasons

The Lebanese-owned department store that became a Southwest Louisiana staple

Published: September 1, 2024

Last Updated: December 1, 2024

Barbara Abdalla Black

Youth choral singers rolling through downtown Lafayette as part of the Abdalla’s Christmas Parade in the 1980s.

Mention the phrase “historic migration” to most folks in southwest Louisiana, and like as not you’ll hear a story about ancestors shoved south from Francophone Canada at the point of a British musket. Yet for all the celebrated history of les Acadiens, Acadiana is home as well to numerous other groups of migrants who put down roots miles away from where they were born—stories that aren’t as frequently told.

In this case, one group put down roots not miles but an ocean away from home: from the Levant, the region of the eastern Mediterranean with which Lebanon shares its etymological origin, and from which migrants have settled all over the world. Indeed, visit Lebanon today and after telling you that it is the only country in the world in which one can ski and swim in the same day (really), your taxi driver will probably also tell you that there are more Lebanese people currently outside Lebanon than there are inside it, another catchphrase locals there never tire of repeating.

Anecdotal though the claim may be, it is not without its intrigue, given that you can pick up a phone book for Lafayette and be almost as likely to find an Azar or a Boustany as you are a Guidry or a Guillory. According to researchers Yvonne Nassar Saloom and I. Bruce Turner, families such as these arrived in Louisiana in the late 1800s, drawn partly by the Francophone communities: “Maronite Lebanese are said to have been attracted to Louisiana,” they write in a 1994 Louisiana Library Association Bulletin, “partly because of the age-old amitié traditionelle (traditional friendship) between Maronites of Mount Lebanon and the French, which began at the time of the Crusades and continued during the centuries of Ottoman rule and through the French Mandate period in Lebanon following World War I.”

Encouraged by ample opportunities for trade in the United States, this wave of settlers reached its peak around the turn of the twentieth century; Saloom and Turner note, “The affinity to Francophone culture which helped this first wave of Lebanese immigrants adjust easily to South Louisiana has been preserved among the succeeding generations as well.” Saloom would know: her father-in-law was Kaliste Saloom Sr., famed merchandiser in Lafayette and namesake of a major bypass, and her husband Kaliste Saloom Jr. was one of Acadiana’s longest-serving judges. Much of her research has served to put this hidden aspect of state history on the map, tracing the origins of multiple Lebanese families into Louisiana.

Among them was a young man named George Abdalla, who arrived in New Orleans around 1895, near the crest of that wave. A polyglot who as of yet spoke little English, George was drawn to the small Lebanese community already present in the southwestern part of the state, and after traveling upriver along the Atchafalaya, eventually settled in Washington, St. Landry Parish. At the start of his merchant career, George would travel from town to town selling his wares from a cart, with his young wife Jasmin (whose English was a little better) often helping him with records and customer relations. By his death in 1951, Abdalla had become the patriarch of a clan that operated over a dozen different department stores and retailers in three cities in Acadiana, and a household name for generations of residents: a remarkable saga for a humble peddler from Beirut.

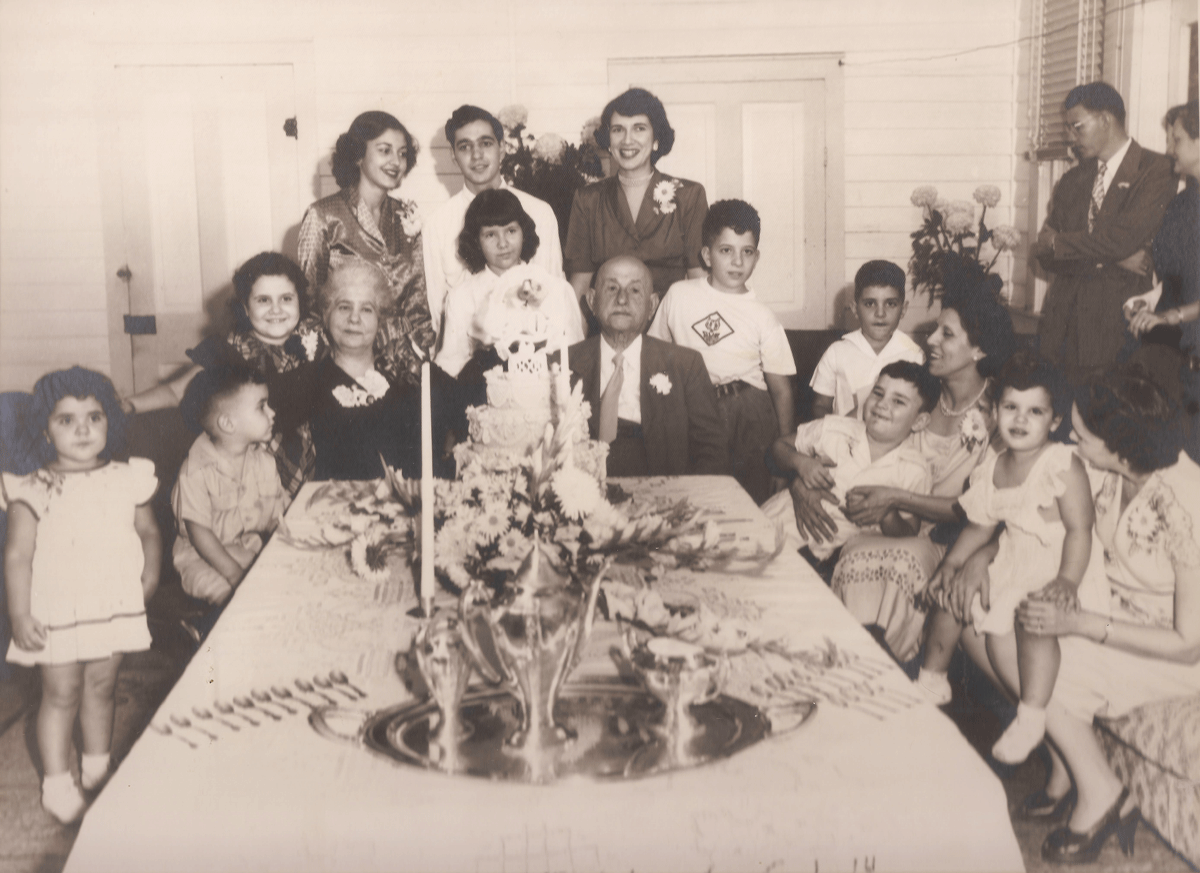

Mr. and Mrs. George Abdalla at a 1949 dinner celebrating their fiftieth wedding anniversary, surrounded by their grandchildren. Barbara Abdalla Black

The Story of a Store

Though precise dates vary, the golden age of department stores typically includes the first half of the twentieth century, prior to the proliferation of suburban sprawl and the arrival of the shopping mall in the 1980s. At the time, commercial density remained largely centralized in historic urban centers, which boasted such destination stores as Marshall Field’s in Chicago and Neiman Marcus in New York, Selfridges in London, and—of course—Maison Blanche and D. H. Holmes in New Orleans. Think: ladies in hats, gentlemen in suits, attentive sales staff in every corner, and fresh, festive decorations perfectly appointed for every season of the year.

The story of Abdalla’s in Acadiana mirrors this trend, and can be divided into three main chapters. After opening his first brick-and-mortar location in Opelousas in the early 1900s—call it the start of chapter one—George moved the business to Main Street in Opelousas in 1910, and he purchased the Sandoz Opera House in Opelousas in 1913. Though for a few more years local operatic performances would continue to be staged there, by 1921 George would not only convert the entirety of the structure to business use but expand it and construct a new brick façade as well.

For those first thirty years, Opelousas would serve as home both for the Abdallas (the family) and Abdalla’s (the store). George and Jasmin had seven children, six sons and one daughter, all of whom came of age working in the family business and who in time would serve as proprietors of their own branches. With both family and stores expanding in size, the next major step forward was in the mid-1930s, when George opened, in quick succession, branches of the store in Lafayette (1933) and New Iberia (1936). By this time George’s sons were of age, and placing them in these new locations signaled the start of the second, and arguably the longest, chapter of the store. The fact that Abdalla’s was able to expand in the middle of the Great Depression, when cash was short and loans were scarce, is a testament both to the business savvy of its founder and to the relationships the family had built in the region—establishing a footprint in each of the three major cities of Acadiana, with additional smaller locations after that (such as a short-lived appliance store in 1946, replaced by a furniture store a year later).

The interior of Abdalla’s Department Store in Lafayette in the late 1980s. Barbara Abdalla Black

One of the celebrated parts of Abdalla family lore concerns just this period, during the war years of the early 1940s. Not only was rationing in effect for fabric and metal, putting a strain on the supply chain and product availability, but sons Edward and Herbert were called up to serve in the army, leaving their wives Irma Belle and Evelina to manage the stores in their absence. Thankfully, both sons were discharged early and able to resume operations, but Herbert and Evelina’s daughter Barbara Abdalla Black still remembers the challenges, both at home and at work, that came with her mother and aunt having to hold down the fort.

In early 1951, George passed away, leaving his widow Jasmin—who knew as much about the business as he did and who had often served as his corporate buyer—as matriarch of the family. (The Salooms, the Abdallas’ friendly competitors across town, had seen a similar transition when Kaliste Saloom Sr. died unexpectedly young, leaving his wife Asma in charge.) For the next twenty-five years, until her own passing in 1976, Jasmin and the board of directors would steer the company’s growth. According to Geoff O’Connell, who wrote an extended profile of the business in the Times of Acadiana in 1982, “The stores split off into separate corporations, although they maintain[ed] a loose federation. . . . The federation means that the stores continue to use the same logos, share buying and credit power, run promotions in tandem, and have primarily the same office policies. [Harold Abdalla] characterizes the relationship between the stores as an ‘harmonious’ one.”

Even with the passing of their founder, however, certain aspects of the business remained unchanged. Recalling a longtime family tradition, Barbara Abdalla Black, George’s granddaughter, said that every weekend each branch of the family would meet for an extended Sunday dinner, a classic Lebanese feast with meze (small plates, including kibbeh, hummus, and labneh) fit to feed dozens. Whether this Sunday practice was more redolent of Louisiana or Lebanese culture is an open question—Rae Gremillion, Kaliste Saloom Sr.’s granddaughter, echoed in a recent interview that the family meals of the Saloom clan were near-daily—but either way said dinner would last for hours, with multiple generations present at the table. Once everyone was as stuffed as the grape leaves on the table, the store proprietors would hold a business meeting to prepare for the coming week, then the evening would conclude with rounds of poker (played by husbands and wives alike). This tradition, Black said, continued for more years than she could count.

In many ways, this second chapter saw business as usual, with a few other milestones punctuating the last half of the twentieth century: in 1967 Abdalla’s opened the beloved Oil Center branch in Lafayette, its flagship location in the Hub City, which would last for nearly forty years (operated by son Herbert), as well as Brother’s on the Boulevard in 1976 (operated by Edward IV, nicknamed “Brother,” and his wife Catherine). Other smaller locations, playing to different market conditions, came and went, such as a location in Abbeville and another in the Mall of Acadiana. Perhaps presaging the third chapter of the story were the closures of the two historic stores in Opelousas in 1985 and New Iberia in 1988, as Acadiana reeled from the oil bust of the era. Yet the footprint lives on: the historic Abdalla’s building in Opelousas, with its iconic corner entryway, now serves as none other than City Hall.

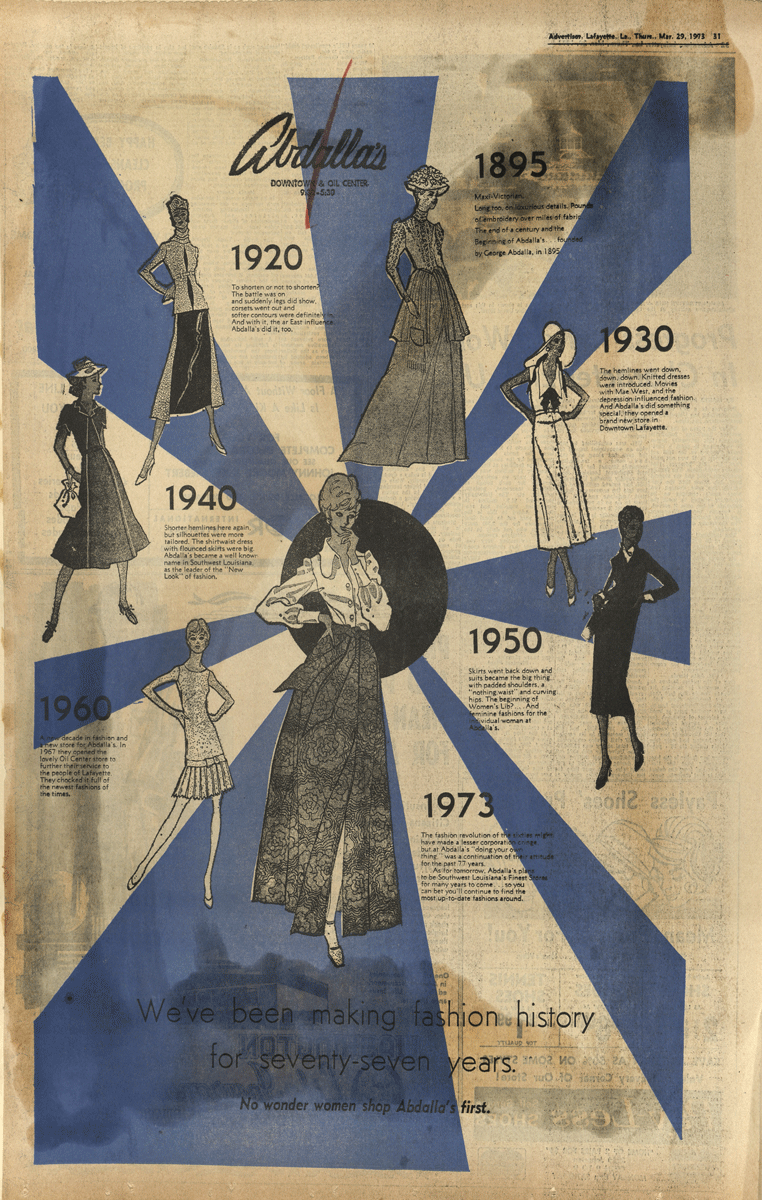

A 1973 advertisement in the Acadiana Advertiser that reads, “We’ve been making fashion history for seventy-seven years. No wonder women shop Abdalla’s first.” Edith Garland Dupré Library at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette

Following the Seasons

The seasons of retail coincide with the seasons of the year in unique and complementary ways. More immediate periods of ordering, receiving, unloading, and stocking overlap with intermittent periods of inventory and renovation and product education, all governed by the larger movements of what brands are coming in (say, from summer to fall) and what styles are going out (say, plaids to solids). Fashion can change at an unpredictable pace, with years of stability upended by years of revolution, which is why buyers must have their eye on the times at all times. This is to say nothing of the most granular rhythms, daily or hourly, of attending to customer needs, refreshing displays, and maintaining an attractive, inviting interior.

Known for their brand awareness, Abdalla’s was on the leading edge of fashion throughout its tenure, regularly importing the latest national lines deep into Cajun country. Brands such as Betty Rose, Estée Lauder, and Tommy Hilfiger (who counted Edward Abdalla III as a personal friend) lined the aisles of each store, often personally selected by whichever Abdalla was in charge. As any local business owner knows, however, to put the sale ahead of the relationship is to put the cart ahead of the horse: having served the residents of the region for decades, the Abdallas were famous for offering personal touches to their customers, whether financing a purchase without credit or, in some cases, personally delivering a needed item to someone in crisis—such as a replacement gown for a Mardi Gras ball.

If hospitality is considered one of the ancestral traits of Middle Eastern societies, such gestures were part and parcel of the Abdalla ethic. So, too, was generosity: firmly believing in giving back to the community that had given their family so much, as the Abdalla clan grew over the last century they found new and inventive ways to increase their civic involvement. For many years the store sponsored an annual 4-H club banquet for area participants, and different sons served on nearly every charitable board and booster group in town: Herbert’s CV alone reads like a telephone directory of area nonprofits, to the extent that reading it today, one marvels at how he managed to also spend time on the Oil Center location floor.

Easily among the most celebrated instances of Abdalla generosity, however, was the Christmas parade in downtown Lafayette. Though the city had for many years sponsored the parade, the early-1980s edownturn eroded municipal capacity to keep it going. Stepping in without hesitation, the Abdallas took over the sponsorship and the organization of the event. Writing in the Sunday Advertiser in December 1985, local columnist Bob Angers publicly thanked the family for their gesture. “The thousands [of residents] who belong to a myriad of volunteer organizations shape the community’s character, inspire better citizenship and provide a sense of purpose for the old hometown,” Angers wrote. “The Abdallas Christmas Parade is a timely illustration of that civic pride. When it seemed like Lafayette would have to discontinue the parade, the Abdallas stepped in to ensure this spectacular event would go on capturing the spirit of the Yuletide.”

Few events get Louisianans in gear like a parade, whether watching or marching in it, and under the Abdallas’ wing the Christmas parade remained one of the destination events of the year. Family photographs preserved from the early 1990s show Jefferson Street lined with spectators, with barely any room to stand as the procession went by. Leading the way were flag bearers and marching bands from across Acadiana, interspersed by a host of vehicles: vintage Rolls-Royces and antique fire trucks, army jeeps and toy cars, sleds and sleighs and even unicycles. Atop the floats were Christmas trees and angels and reindeer of course, but also mimes, clowns, candles, gingerbread houses and castles, Nutcrackers and wise men, revelers dressed up as gift boxes—a gentle reminder, perhaps, in case you hadn’t yet finished your shopping—plus snowmen, choristers, candy canes, and finally, Santa Claus, dispensing peace on earth and goodwill toward men and a few other throws besides.

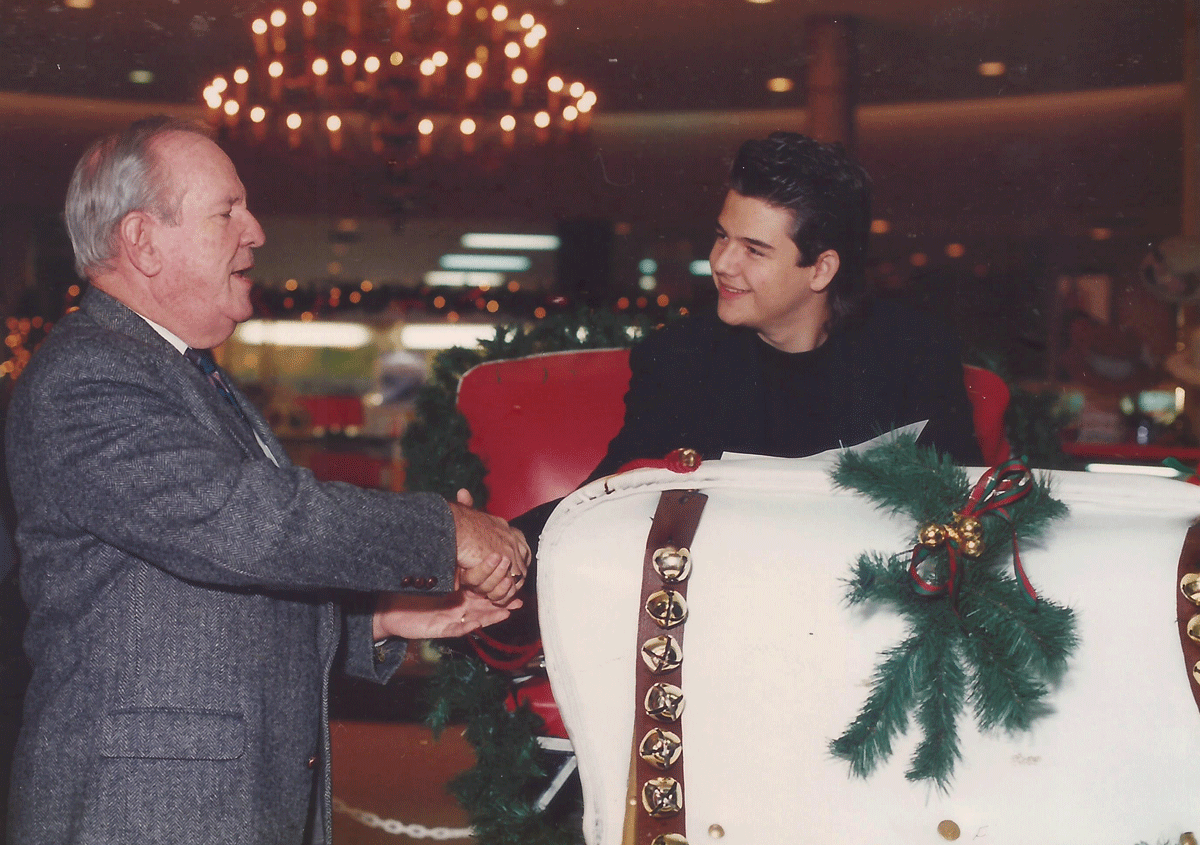

Proving the Abdallas’ ability to bring the height of celebrity to the region alongside the height of fashion, the 1992 parade featured as grand marshal none other than Brandon Call, the actor who played J. T. Lambert on the hit sitcom Step by Step and king of teen heartthrobs at the time. Santa Claus, move over: not only did Call ride in a sleek convertible through downtown Lafayette, but he graciously took the time to tour the Oil Center location and sign autographs, with a line stretching far outside the store to meet him. Every parade has its prized throw, and for Call’s adoring fans, there can be little doubt what that year’s trophy was.

Brandon Call, Step by Step star and teen heartthrob of the time, greeted fans and signed autographs in Abdalla’s Lafayette store in December of 1992. Barbara Abdalla Black

A Season of Farewells

Here in Louisiana, seasons flow seamlessly into one another: Christmas into Carnival, Carnival into festival, festival into football, and football into Christmas—to say nothing of the four cardinal seasons of oyster, crawfish, crab, and shrimp. Just as our favorite subject at the lunch table is what we’re having for dinner, even as we’re making the most of the current season, the next one is always around the corner.

Indeed, soon after that moment captured in those parade photographs, the third and final chapter of the Abdalla’s story began, a season of thanksgiving as George’s seven children began to retire and consolidate their holdings, and members of the second generation began to pass away. In 2005 the Oil Center location in Lafayette closed, concluding 110 uninterrupted years of stores named Abdalla’s in Acadiana. Facing unexpected medical complications, Edward IV decided to close Brother’s on the Boulevard in late 2019, the announcement prompting such a massive rush by area residents that the Acadiana Advocate reported on a “four-day buying frenzy at the 10,000 square-foot store” and its busiest days of trade ever recorded in its forty-three-year history—a fitting end to a long-beloved institution.

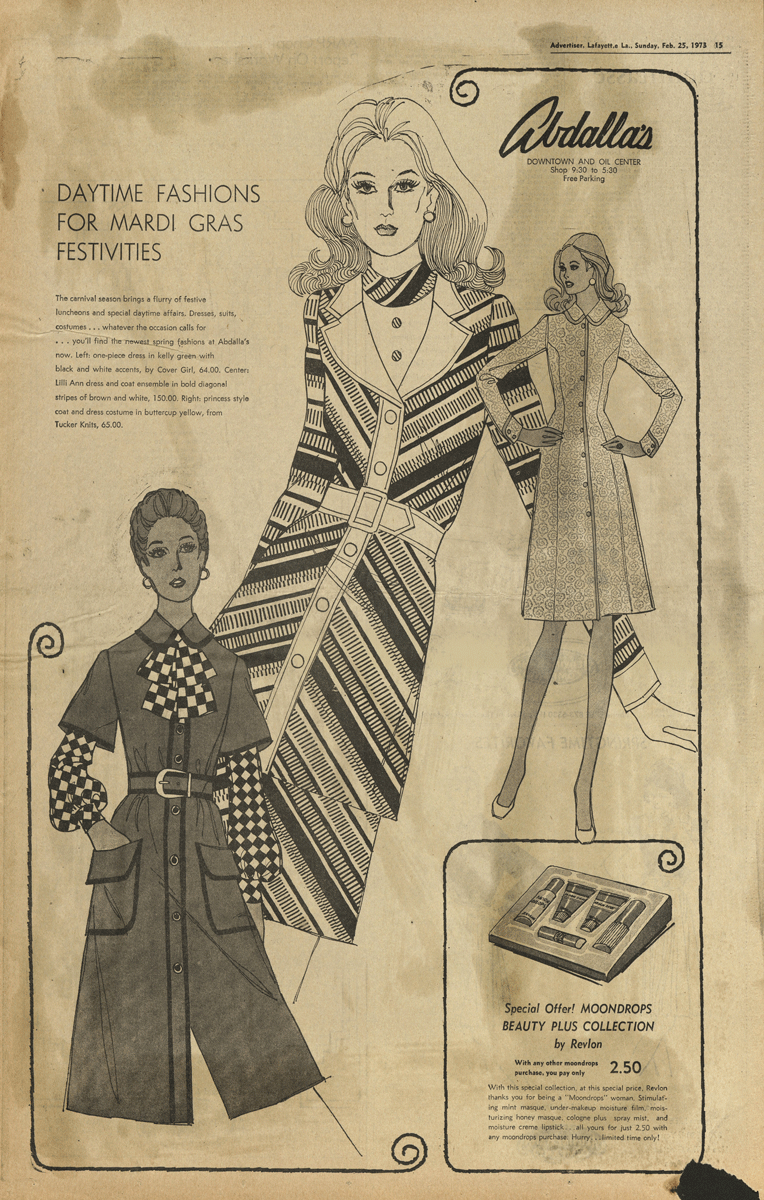

A 1973 advertisement in the Acadiana Advertiser for Abdalla’s department store touting, “daytime fashions for Mardi Gras festivities”. Edith Garland Dupré Library at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette

The story of the Salooms parallels in many ways the story of the Abdallas, as after the 2006 passing of Alice Saloom, who had inherited the family business from Asma, Saloom’s Store shut its doors as well. Indeed, for all independent retailers in the greater Lafayette area, the arrival of national chains at the turn of the millennium meant increased economic pressure. John McKnight, who worked at Abdalla’s for forty straight years—including as financial controller of all the stores from 1960 to 1981—notes that self-service displaced staff service in a way that was difficult to counteract. “Abdalla’s was always based on the quality of clothing and the service,” McKnight said. “With the larger retailers out there, it was a different type of operation, where the customer had to search for assistance. It was never that way at Abdalla’s. But still you only have one economic pie, and the more those stores came into the area, the slices just got smaller for everyone.”

Though individual family members still continue to operate smaller, more niche concerns, the last few years have seen this third chapter draw gently to a close. One might imagine that these closures would see the family name fade into the horizon, but little could be further from the truth. Rather, to this day even the mention of Abdalla’s prompts conversations across the region: simply on hearing the word, for example, an archivist at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette immediately recalled buying one of her favorite dresses in high school at the Oil Center location, a dress that she vowed to go back and dig out of her closet as soon as the library closed. Or, outside the Opelousas location, watching the exterior repainting project then underway, this writer met a Creole gentleman in his sixties who, without any prompting, introduced himself and reminisced about his mother’s employment there, and how highly she regarded her employers.

Driving down Kaliste Saloom Road to the Lafayette airport, the same sentiment still rings true. Shopfronts may close, but the memories of them will linger—for what, at heart, is the story of a department store but the story of its patrons, and the story of the seasons of their lives? At each new milestone we reach—each graduation, each sweet sixteen or quinceañera, each Mardi Gras ball or wedding or funeral—we mark it just as much by what we wear that day as by what we do, no matter whether the occasion is as quotidian as dinner or truly once-in-a-lifetime. For this is the story of Abdalla’s, over a century in the making: a story of gratitude, respect, and admiration, woven not just in fabric but in the depth of relationships over five generations. It’s often said that “clothes make the man”: but for that to be true, someone must first outfit the person, a skilled tailor or merchant with an eye for detail and a devotion to service, someone who views their work as a clothier as among the highest of callings. Asked to take stock of more than just their inventory, any such retailer will tell you they count their legacy not in the sales they manage or the profits they earn, but in the joy they bring to each new generation.

And that kind of character will never go out of style.

A writer and researcher, Benjamin Morris, PhD is the author of Ecotone (Antenna/Press Street Press), a poetry collection inspired by the coastal forests of Louisiana.