A Creole Activist in the Age of Jim Crow

The Work of Alice Moore Dunbar-Nelson

Published: November 30, 2020

Last Updated: March 22, 2023

Photo by R. P. Bellsmith; Alice Dunbar-Nelson Papers, Special Collections, University of Delaware Library, Museums and Press

Alice Moore Dunbar-Nelson as a young woman, ca. 1895.

She might have looked peaceable, but she never was. And she was a modern woman: she spoke up for herself. That fight for the right to vote grew from her feisty personality and her New Orleans upbringing.

Creole Black Louisianans shared French heritage and the Catholic religion; Alice had no French heritage, she was Protestant, she was female. But Dunbar-Nelson joined a long line of outspoken Creole New Orleans champions of universal suffrage and the rights of African Americans, extending from before the Civil War right through the Jim Crow era. This insistence on full rights of citizenship came via traditions of the radical and outspoken free men of color who rose to political prominence during Reconstruction and built on notions of equality grounded in their French heritage. To this, Alice added the cause of the rights of women.

A lifelong writer, perpetually involved in public affairs, she was born Alice Ruth Moore in New Orleans in 1875, and she left the city in her early twenties. Before she left, she soaked herself in the city’s atmosphere, wrote stories and poems steeped in its history, and, as a college student, slipped easily into the orbit of Creole circles of bright young people, eagerly debating politics and topics of the day.

With her mother Patsy and sister Mary Leila, Alice grew up in neighborhoods on the edge of respectability—grand homes were only a few blocks up the street. Their neighbors were both white and Black. The family appeared in city directories and, in the US census, were listed as “M” for Mulatto.

Patsy had been born enslaved in rural St. Landry Parish. She was unmarried and her daughters apparently had different fathers (both with the last name Moore) who took no part in their lives. Despite their circumstances, Alice, Leila, and Patsy eagerly took advantage of what New Orleans could offer them. Glimpses of their New Orleans life are fictionalized in Alice early stories, and the Moores’ names appeared in a local African American newspaper, the Weekly Pelican: Alice’s being on the honor roll at Southern University Prep School (located on Magazine Street) merited notice, and so did Patsy, Alice, and Leila attending a tea party given by Mrs. Eliza Geddes in March 1889.

Alice attended Straight University (now Dillard), and her 1892 graduating class named her Class Poet. She began teaching in New Orleans public schools, taught second grade at Marigny School in the Seventh Ward, and became active in teachers’ organizations.

Meanwhile, she was writing. She set her stories in New Orleans. She also wrote poems. She was determined to make money at her craft and regularly sent material to out-of-town publications. Her work was bringing her notice: On January 18, 1895, the dominant white newspaper, the Picayune, reported “the elite of the colored population” watched “the farce-comedy, entitled ‘No End to a Joke,’ written by Alice Ruth Moore.”

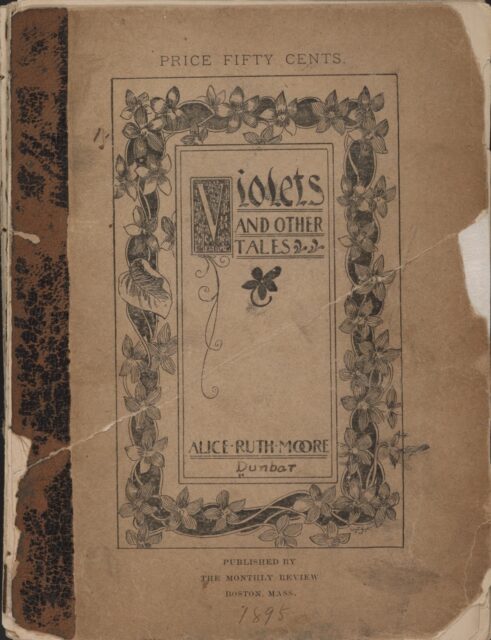

Her first book, Violets and Other Tales, was a collection of stories and poems published in 1895 under the copyright of the Boston Monthly Review. The atmosphere of New Orleans pervaded the work. Alice did not designate the race of her characters and followed the short story conventions of the day (including the occasional surprise ending). Her writing was adroitly done and is still enjoyable today. On August 18, 1895, the Picayune gave her a bad review, calling the book “slop.” It hurt, but did not daunt her.

In fact, the paper would later praise her work. On May 3, 1896, the Picayune reported on Decoration Day ceremonies honoring military dead in Chalmette: “Miss Alice Moore read an original poem, perfect in construction and smooth in its flow.” (The poem was “Chalmette,” from Violets.)

Alice’s next venture into writing was journalism, a calling that would last her lifetime. The Journal of the Lodge was a publication of the New Orleans Knights of Pythias, a fraternal organization. (The recently renovated Pythian Temple building, at 234 Loyola Avenue, was constructed for them.) Alice wrote the “Woman’s Column.”

A lithograph image of Alice appeared on the front page of the August 18, 1894, edition, with a biography. “The only colored female stenographer and typewriter in the city,” her “excellent articles on race and sex” had already won awards. In her first column, Alice used a breezy, opinionated style to chronicle her own interests, while including women’s news (reports on teachers’ groups, new trends in education), politics (criticism of lack of support for Ida B. Wells’s anti-lynching campaign), and women’s suffrage (noting the first woman nominated for a state office in Wyoming). It was a pattern she would follow throughout her years as a columnist.

But as Alice reached her twentieth birthday, her life changed. She fell in love—in the most romantic way possible for a young poet.

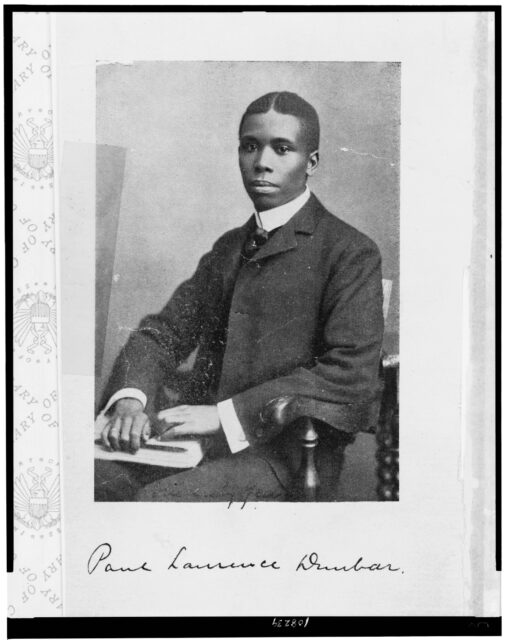

In April of 1895 the Boston Monthly Review published one of her poems, and included her photograph. Nationally known Black poet Paul Dunbar was so smitten with her image, he wrote her. They began a passionate correspondence and thought themselves the new incarnation of Robert Browning and Elizabeth Barrett.

Dunbar fell in love with his image of Alice. By the time they met in person, Alice’s life had changed. She, Patsy, Leila, and Leila’s new husband left New Orleans in 1896 for West Medford, Massachusetts. In 1898, Alice married Paul Dunbar, and they moved to Washington, DC, where they entered the highest levels of African American society. Her dream quickly turned nightmare.

Alice respected Paul’s work, and they had grown fond of each other. But he was an alcoholic and abusive husband. After a beating so brutal that a friend wrote Booker T. Washington about it, Alice left him. The marriage ended in 1902. Paul died in 1906. For the rest of her life she would carry his name, and she kept his work alive with lectures and by publishing literary anthologies: The Dunbar Speaker and Entertainer and Masterpieces of Negro Eloquence.

Without Paul, Alice had to support herself and help her family. She moved to Wilmington, Delaware, with Patsy, Leila (whose husband had left), and Leila’s children. From 1902 until 1920, she served on the faculty of Wilmington’s Howard High School. She was briefly married to a fellow teacher, Henry Callis; they had an amicable divorce.

Alice, during her suffrage campaign in Delaware and the surrounding states, pointed out that giving women the vote would double Black political power.

In 1915, while still teaching in Wilmington, Alice became a regional field organizer for women’s suffrage. In 1916, Alice married Robert “Bobbo” Nelson. He was a journalist, and from 1920–1922 they published the African American Wilmington Advocate newspaper.

During World War I, Alice served on the Women’s Committee of the Council of Defense (she was the only Black member) and contributed an essay to Scott’s Official History of the American Negro in the World War.

Alice valued military service. Her early poem “Chalmette” praised the sacrifice of the military dead in the graves at the battle site. Her later poem “I Sit and Sew”—bemoaning that as a woman she could only sew on the sidelines of World War I—was included in Countee Cullen’s 1927 Caroling Dusk anthology of Black poetry during the Harlem Renaissance. In 1918, her play “Mine Eyes Have Seen,” about a young Black man drafted in the final year of World War I, was published in the Crisis, the magazine of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.

Alice’s view of military service as a welcome necessity was akin to that held in previous centuries by free men of color in New Orleans. They had pride in their home city: they were ready to take up arms to defend it, and they actively used this as evidence of their worthiness for citizenship and inclusion in civic life. They formed active militias in the colonial era. When the American flag was raised at the Louisiana Purchase, they proudly bore arms in the Place d’Armes. They fought in the Battle of New Orleans. They fought in the Civil War (although briefly in the Confederate Army, the 731 free Black New Orleans soldiers and 33 free Black militia officers who stayed in uniform switched to the Union side). Status as a military veteran was, for free men of color, a positive factor in political involvement, especially after Reconstruction, when they used the common bonds of military service to create activist alliances with other Black men, both formerly enslaved and freeborn.

Alice, during her suffrage campaign in Delaware and the surrounding states, pointed out that giving women the vote would double Black political power. When those states voted on women’s suffrage, Alice’s positive effect could be felt. When the suffrage effort focused on a Constitutional Amendment, Alice continued her advocacy work as an active proponent.

Alice was fired by Howard High School in 1920 for taking leave to go to an anti-lynching conference. Despite that, she still worked hard in the unsuccessful attempt to pass an anti-lynching law in Congress.

1905 Photograph of Paul Dunbar, included in his book Lyrics of Sunshine and Shadow. Library of Congress

After women got the vote, Alice flexed her political muscles and helped defeat a sitting US Senator from Delaware, Dr. Caleb Layton. Alice had been a staunch Republican and served on the party’s State Central Committee. In 1922, after Republican Layton refused to vote for the Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill, Alice launched a voter registration drive, adding twelve thousand new voters to the rolls. Layton lost by seven thousand votes—the same as the number of Black voters who supported his opponent. Alice became a Democrat.

When her teaching career ended, Alice’s income came from her writing. Although she wrote and published longer stories under various names, her newspaper columns were her main output. These columns were true to her first aims and had various titles (her favorite column name being On Dit—French for “rumor has it”). They included readable short items covering a range of African American–centered topics: politics, consciousness raising, supportive bits of news, art and music criticism, women’s issues, fashion, government matters, personality pieces, and club notes, with a little gossip thrown in.

In early March 1930, five years before her death, Alice’s diary records a visit to New Orleans. The Louisiana Weekly, on March 3, reported a plan to spend $2 million for construction of a Dillard University campus (the new name for the combined Straight College, Alice’s alma mater, and New Orleans University).

Alice wrote her diary entry that day from Straight’s Stone Hall. “The dream of my childhood … thirty-eight years ago this May since I graduated.”

The next day was Mardi Gras. “It’s been such a lovely day that I can’t write about it. And yet I have done nothing extraordinary. . . . But the old friends, the streets, the houses . . . and just everything. I can’t describe, only feel. Every inch of ground feels sacred,” she wrote on Wednesday, March 5.

Two years later Alice and Bobbo moved to Philadelphia when he was named a member of the Pennsylvania Athletic Commission in 1932. Alice was barely sixty years old, but she was not in good health, and she died after being hospitalized for a heart ailment on September 18, 1935. Her ashes were scattered over the Delaware River, and her archives, containing scrapbooks, clippings, souvenirs, and manuscripts from a lifetime of activism and writing, were placed in the library of the University of Delaware. She was survived by her sister’s children, Bobbo, and her stepchildren.

Carolyn Kolb is currently writing profiles of Kingsley House staff, clients, and board members for a 125th anniversary project, and working on a series of video programs on Jefferson Parish history for the Jefferson Parish Public Library.

This article is presented as part of Who Gets to Vote, an initiative of the Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities intended to build public understanding of the complicated history of voting rights in America. Who Gets to Vote is part of the “Why It Matters: Civil and Electoral Publication” initiative administered by the Federation of State Humanities Councils and funded by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.