Sound Advice

America Hears Itself

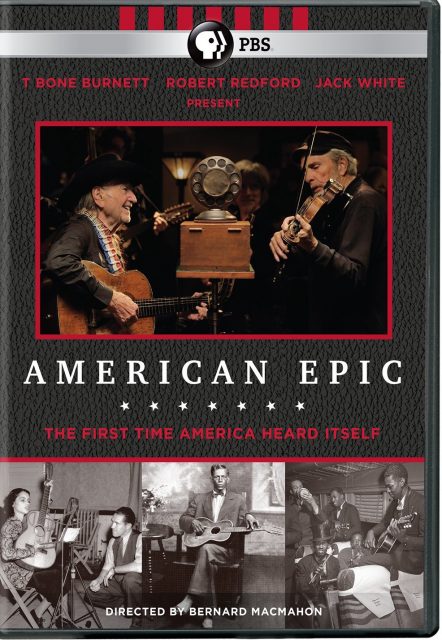

New documentary on traditional music combines vintage and contemporary material

Published: September 5, 2017

Last Updated: December 21, 2018

Musician and singer Cléoma Breaux Falcon recorded the first Cajun record with her husband, Joseph Falcon, on April 27, 1928.

The latest project to take on this rich, complex topic is a multimedia presentation entitled American Epic (PBS). For the most part this massive, ambitious work is artistically successful, and it comes highly recommended. It achieves many moments of greatness, especially on two levels: the clarity of sound restoration on old recordings, originally released as 78s, that constitute its central theme, and the thematically effective use of rare and fascinating historic footage.

American Epic’s basic concept is examining the commercial recording of traditional music, which rapidly accelerated in the 1920s. The phrase used by the series’ creators—the actor Robert Redford, the music producers T Bone Burnett and Jack White, the film director Bernard McMahon, and the film producer Allison McGourty—to refer to this moment in history is “the first time America heard itself.” With radio in its infancy (the first American station began broadcasting in 1920) and many rural dwellers living without electricity, a significant number of ’20s traditional musicians still learned by oral/aural tradition only, within their local communities. “The first time America heard itself” refers to the joy and incredulity that many musicians experienced during the initial playback of their debut recordings. From then on, recordings became an ever-increasingly important mode of musical dissemination.

In the 1920s, many record company executives came to realize that they could significantly increase profits by exclusively recording songs for which they owned the copyrights, thus avoiding payments to songwriters and publishers whose material they did not control. To find fresh, unpublished songs—virgin intellectual property, as it were—the record companies shunned the commercial world of vaudeville and Tin Pan Alley. They turned instead to the largely ignored realm of Southern folk-rooted music. Traditional songs with archaic origins and no definitive author presented minimal risk of copyright-infringement litigation. That risk could be further reduced if songs were changed slightly and then presented as original new compositions. This became standard practice, especially in blues and country music.

“The first time America heard itself” refers to the joy and incredulity that many musicians experienced during the initial playback of their debut recordings.

Some rural Southern musicians were brought to the large cities where the record companies had their own studios. But to find musicians from remote areas, the companies would often bring a portable studio and set up shop in a town such as Bristol, which straddles the border of Tennessee and Virginia. (Portable is a relative term, because the technology of the time necessitated enough trunkloads of equipment to fill a large room, shipped ahead by railroad.) The companies would place notices seeking musicians in local newspapers, and see who turned up to audition. Some who responded turned out to be among the most important stylists of their generation–for example, The Carter Family and Jimmie Rodgers. Such recording activity, in these temporary locations, is a major theme in American Epic.

The commercial record companies, some of which remain active today, traveled south solely to make money. Cultural documentation was never a consideration, and these companies’ executives had little or no affinity for regional music beyond its value as a product. But these executives functioned nonetheless as de facto folklorists, by preserving music that would have gone unrecorded and that has long since disappeared in many cases. Professional folklorists such as Alan Lomax were also active at this time, working for such organizations as the Library of Congress. But Lomax and his colleagues tended to reject material with a perceived commercial tinge, which the record companies, by contrast, embraced.

American Epic focuses on an almost overwhelmingly wide range of material: various country styles, blues, early jazz, Cajun and Creole music, gospel, Hawaiian music, songs in Spanish from Puerto Rico and Mexico and Texas, ceremonial music of the Hopi tribe, a tribute to fallen Civil War soldiers, the hybrid sound of jug bands, political protest songs, early precursors of rock, and more. There are four video segments. Three of them, each an hour in length, focus on vintage recordings, the musicians who made them, and the cultural context in which the music evolved; a fourth, longer segment features new recordings of songs from the previous three. There is also a glorious five-CD set of one hundred reissued 78s, a fifteen song soundtrack sampler, available on CD and vinyl, and a 279-page book with informed commentary and transcribed interviews. Curiously, the book’s publisher, Simon & Schuster, did not see fit to furnish an index, which would have made the book far more useful for further research.

American Epic

www.americanepic.com

Rather than attempting to discuss all the musicians who appear on the five CDs, the main narrative device used in the visual component of American Epic is extended profiles of key artists from different genres. These include the country trio The Carter Family, the raucous Memphis Jug Band, the inspirational gospel singer Elder J. E. Burch, the Hawaiian steel guitarist Joseph Kekuku, and the passionate norteño singer and guitarist Lydia Mendoza. Instead of presenting a host of music experts as talking heads, American Epic takes a novel and commendably populist approach by interviewing descendants of the featured musicians, or people who actually knew them. The most effective use of this technique can be seen in a segment about Elder J. E. Burch, a deeply soulful gospel singer from Cheraw, South Carolina. In Cheraw, director Bernard McMahon interviewed an elderly man named Ted Bradley, who had been a member of Burch’s congregation. The scene where Bradley sees a photo of Burch for the first time in seventy years is truly touching, and such moments stand among the series’ greatest strengths. (Another native of Cheraw was the acclaimed jazz trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie, who cited Burch’s church services as a major musical influence in his autobiography To Be, or Not . . . to Bop.)

Some interviews, however, distinctly lack this vital emotional impact. At the site of the former Dockery Plantation in Mississippi, two young relatives of the influential blues guitarist Charley Patton aptly assess the racist exploitation of the sharecroppers who constituted Patton’s main audience. But, on a personal level, they evince little sense of connection with Patton or his music. In this same segment, William Lester, the executive director of the Dockery Farms Foundation, gushes that the plantation is “the birthplace of the blues.” Such exaggeration, commonplace in interviews with musicians and musical entrepreneurs, is typically accepted as artistic license, with no expectations of strict accuracy. But in the script of American Epic, the narrator Robert Redford similarly states, in a quite definitive tone, that the Carter Family were “the founders of modern country music.” Such an inaccurate, sweeping overstatement should not be made in an official role, by a respected, high-profile professional, in the context of a national-level project. The Carter Family were vitally important figures in country music history, of course—but they were not its sole founders, nor was anyone else.

There are also some visual errors in an otherwise strong segment about Cajun music, which focuses on the Breaux family. The narration makes frequent references to bayous, while repetitious bayou scenes roll by on the screen. This reinforces the popular, stereotypical misconception that Cajun music and zydeco hail from an exotic/aquatic world that teems with alligators, Spanish moss, and the like. In reality the home turf of most such music is an expanse of flat farmland known in south Louisiana as the prairies; there is far less musical activity along the bayous. In addition, part of the Cajun-music segment features historic footage from the New Orleans Mardi Gras, thus depicting an entirely unconnected tradition. These are relatively minor criticisms given the generally high quality of American Epic. But the series’ prevailing high standards makes such errors all the more puzzling.

It is commendable, however, that American Epic chose to focus on the Breaux family—whose contributions to Cajun music have gone somewhat under-recognized—both via this video segment and the presence of three songs on the CD collection. These include Cléoma, Amédée and Ophy Breaux’s performance of “Ma Blonde Est Parti,” which later became known as “Jolie Blonde” thanks to subsequent renditions by The Hackberry Ramblers and, most popularly, by the Cajun-swing fiddler Harry Choates. Several of Amédée Breaux’s grandsons remain active on the Lafayette music scene today, and they appear in American Epic both discussing their grandfather’s music, and performing it along with other musicians, including Louis Michot of the Lost Bayou Ramblers, and Ann Savoy. Cajun and Creole music is further represented on the CD collection in dynamic performances by Columbus Frugé, Amédé Ardoin and Dennis McGee, Berthmost Montet and Joswell Dupuis, and on a lovely, lilting instrumental by fiddler Delma Lachney and guitarist Blind Uncle Gaspard. North Louisiana is represented in high style by Lead Belly, playing solo twelve-string guitar with more drive than most five-piece bands. New Orleans gets surprisingly little attention, given its primal importance in the raison d’être of this project. A Dallas-based group of Crescent City expatriates called Frenchy’s String Band contributes some early hot jazz. A song by the New Orleans blues guitarist Richard “Rabbit” Brown sounds bland, generic, and devoid of Big Easy style. And, despite its title, “New Orleans Stop Time” presents two highly entertaining musicians—Bumble Bee Slim and Memphis Minnie—who have no New Orleans connections. That is all.

The fourth visual segment of American Epic features contemporary artists recording on the equipment of the ’20s and ’30s. A ten-year effort went into assembling this huge, complex, and intricate machine from spare parts, because none of the original recorders survived intact. Seeing this equipment in action vividly conveys the remarkable evolution and miniaturization of recording technology. The actual performances vary in quality, however. High points include Willie Nelson and Merle Haggard joining forces on a charming duet; the multi-instrumentalist Jerron “Blind Boy” Paxton demonstrating why he is considered among the most skilled and charismatic African-American interpreters of material from the American Epic era; and the Lost Bayou Ramblers performing a rocking rendition of “Allons à Lafayette”—the first Cajun song ever recorded.

A collection of American Epic’s proportions cannot possibly be absorbed in a single setting. Instead, one might obtain the five-CD set and play it while driving around over the course of a month or so, to let all this great music sink in. Following such osmosis, watching the DVDs is the next logical step. The investment of time will be well worthwhile.

Ben Sandmel is a New Orleans-based freelance writer, folklorist, and producer and is the former drummer for the Hackberry Ramblers. Learn more about his latest book, Ernie K-Doe: The R&B Emperor of New Orleans, by visiting erniekdoebook.com. The K-Doe biography was selected for the Kirkus Reviews list of best nonfiction books for 2012.