Summer 2025

Arresting History

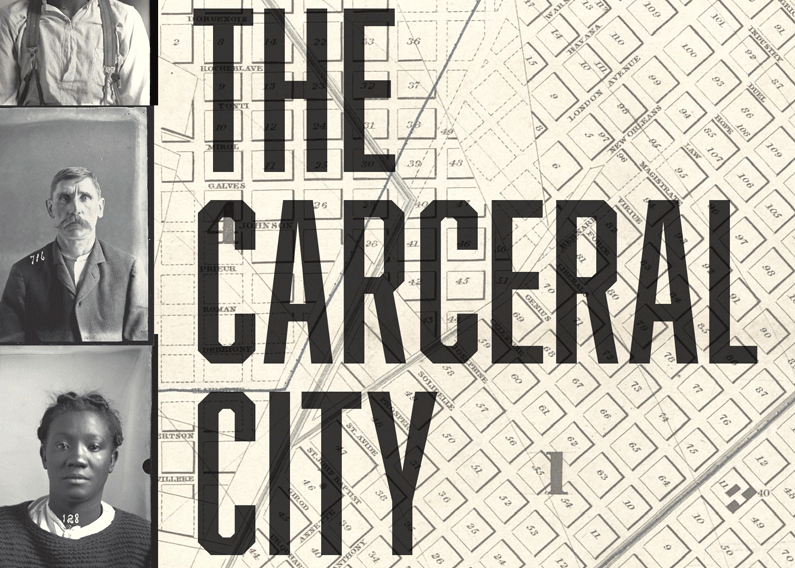

Carceral City: Slavery and the Making of Mass Incarceration in New Orleans, 1803-1930 by John Bardes is the 2025 Book of the Year

Published: May 30, 2025

Last Updated: May 30, 2025

University of North Carolina Press

Carceral City: Slavery and the Making of Mass Incarceration in New Orleans, 1803-1930 by John Bardes is the LEH’s 2025 Book of the Year. Published by the University of North Carolina Press, Carceral City traces the complex history of modern-day mass incarceration to antebellum slavery in New Orleans. The following is an excerpt from the book’s introduction.

On the night of August 18, 1943, after several unsolved robberies sparked fears of a new crime wave and as the nation waged unrelenting war on tyranny overseas, New Orleans’s police chief ordered the arrest of all the “vagrant negroes.”

Police began sweeping street corners, dance halls, and barrooms for Black men, charging them all with vagrancy: the crime of appearing idle and unemployed. By August 20, police had arrested nearly 100 “vagrant” Black men; after another two days, more than 400. By then, suspects in the robberies had been found and charged. Yet the arrests continued. Citing Louisiana’s patriotic duty to maximize war production, New Orleans mayor Robert Maestri vowed to prosecute the “wholesale arrests” of Black vagrants until all the jobless “loiterers” had been driven “to jail or to work.” In court, virtually every detainee protested that he in fact already had a job. On August 27, the number of vagrancy arrests surpassed 600. By September 4, their number neared 1,000—equivalent to roughly 2 percent of all adult Black men in New Orleans.

The prisoners were herded into an infamous New Orleans prison known as the House of Detention. After several days, as the first detentions were set to expire, a fleet of trucks pulled up, provided by the American Sugarcane League. The prisoners were released but given a choice. Either they boarded the trucks—bound for rural plantations, where they would be forced to accept jobs harvesting sugarcane at fixed wages—or they would be immediately rearrested, reconvicted, and reincarcerated for vagrancy. Daniel Byrd, president of the New Orleans chapter of the NAACP, called it “nothing short of peonage.”

That summer, similar mass arrests of Black workers on vagrancy charges erupted in Birmingham, Jackson, Miami, Dallas, Wilmington, and other cities throughout the South. The governors of Alabama, Mississippi, and North Carolina declared statewide wars on vagrancy. “Idleness can not, and will not, be tolerated,” Mississippi governor Paul Johnson declared on August 31, “while our sons are fighting and dying for the principles we hold so dear.”

Americans familiar with the history of Jim Crow have encountered similar stories: mass arrests and confinements, targeting Black Americans arbitrarily, often in the service of elite white economic interests. Yet beginning here erases the first half of the story. In fact, the policing and carceral practices on display in 1943 date to the early nineteenth century.

For most of the late twentieth and early twenty– first centuries, New Orleans has been the world’s carceral capital.

Consider, for a moment, the New Orleans House of Detention itself. Once known as Louisiana’s “slave penitentiary,” the prison had been founded in 1805 for the confinement and torture of resistant and fugitive enslaved people before their return to their owners. By 1943, this institution had been in the continuous business of conveying Black people to sugar plantations for 138 years. Before Emancipation, police brought enslaved people to this prison as “runaway” slaves. After Emancipation, police brought free people to this prison as “vagrant” wageworkers. In other words, antebellum coercive tactics directly informed the design of postbellum coercive tactics. The ways that New Orleans policed, imprisoned, and forcibly redeployed Black Americans in the twentieth century derived from the ways that New Orleans had policed, imprisoned, and forcibly redeployed enslaved people in the early nineteenth century.

For most of the late twentieth and early twenty- first centuries, New Orleans has been the world’s carceral capital: the city that incarcerates people at the highest rate of any American city, within the state that incarcerates people at the highest rate of any American state, within the country that incarcerates more people than any other nation on the globe. New Orleans is the epicenter of what scholars have termed “mass incarceration”: the explosive growth of imprisoned populations, disproportionately Black, since the 1970s.4 No country on earth has ever caged a higher percentage of its own people or of the human race. Black Americans account for 13 percent of the US population but nearly 40 percent of the US prison population, raising fundamental questions regarding American identity, race, violence, inequality, the legacy of slavery, and the meaning of freedom. Scholars of mass incarceration often point to proximate causes: labor dislocations during the 1970s, the nation’s ill-conceived “wars” on drugs and crime, “broken windows” policing, and backlash against the civil rights movement, to name a few. Other scholars locate mass incarceration on a longer historical timeline that stretches as far back as the late nineteenth century, when police and prisons were bastardized into appendages of white power in the aftermath of slave emancipation and during the codification of Jim Crow.7 Yet as this book shows, the features associated with mass incarceration—astronomical incarceration rates, state violence on a vast scale, the targeted internment of entire populations—began in New Orleans long before the late twentieth century, or Jim Crow. Indeed, by the 1820s, New Orleans incarcerated enslaved residents at higher rates than the city, state, or nation incarcerates Black Americans today.

This book examines the rise of state coercion in the world’s carceral capital, from the Louisiana Purchase in 1803 through to the nadir of Jim Crow in the early twentieth century. In legal parlance, public officials’ ability to coerce peoples falls under the umbrella of state police power: generally defined as the power of governments to regulate and restrain populations and property for the public good, though restricted here to the coercion of laboring people through the threat or use of imprisonment. State police power is an old concept: rooted in early modern European law, it predates the modern connotations of the word “police,” today referring to the municipal agents tasked with maintaining order. In US constitutional law, state police power derives from the Tenth Amendment to the Constitution, which reserves to the states all powers not delegated to the federal government.

Whereas previous scholars have argued that slavery stymied coercive state power, the central argument of this book is that many antebellum slaveholders were fiercely committed to, and deeply reliant upon, the use of police and prisons to coerce enslaved and free labor. Decades before the Civil War, southern port cities created the first municipal police forces in the United States, jailed Black and white workers at astronomical rates, and contrived massive slave prisons and specialized slave penal labor systems to maintain control and maximize profit. Emancipation disrupted, but did not destroy, the publicly managed policing and penal systems developed within cities: rather than starting anew, southern authorities adjusted, adapted, and refined the prisons and policing practices already at their disposal—including prisons and policing practices originally devised for the subjugation of the enslaved—into the brutal coercive machinery of Jim Crow. In other words, the histories of racialized policing and imprisonment in the United States begin in the early antebellum urban South, with the very origins of prisons and municipal police. To peer within New Orleans’s “slave penitentiary” is to witness the roots of Jim Crow and our nation’s current carceral crisis.

Copyright © 2024 by the University of North Carolina Press. Used by permission of the publisher. uncpress.org.

John Bardes is a historian of slavery, race, and Emancipation in the 19th century United States. He is an assistant professor of History at Louisiana State University.