Magazine

The Burning of Alexandria

In the final days of the Red River campaign, a mutinous band of Union soldiers carried out a senseless and devastating act

Published: January 13, 2015

Last Updated: May 13, 2019

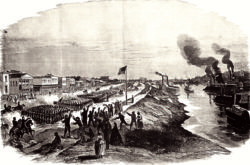

The Historic New Orleans Collection.

Black-and-white reproduction of an illustration depicting the triumphant entry of the Union army in Alexandria.

The white camps disappeared; artillery was hauled away from the breastworks; sick men and stores were transferred to vessels; and at the appointed hour, troops fell into line and filed out of the streets of the town of Alexandria, where they had lived for eighteen days. Then they pursued the road that led along the levee of the Red River.

Having marched a few miles, the men heard in their rear the roar of distant explosions. The Red River dam, the product of their labor and skill, was being blown to pieces. They also observed a huge column of black smoke ascending the sky, in the direction of the lately vacated town. Their surmises concerning the remarkable spectacle were soon confirmed by the news that incendiary soldiers had caused the destruction of the largest and finest portion of Alexandria.

That evening a soldier in the 128th New York Infantry took the opportunity to make an entry in his diary when the regiment halted:

Eight miles below Alexandria. The Jay-hawkers [Louisianans loyal to the Union] kept their promise to burn the place rather than have it go into the hands of the enemy again. About daylight this morning cries of fire and the ringing of the alarm bells were heard on every side. I think a hundred fires must have been started at one time. We grabbed the few things we had to carry and marched out of the fire territory, where we left them under guard and went back to do what we could to help the people. Fires were breaking out in new places all the time. All we could do was help the people get over the levee, the only place where the heat did not reach and where there was nothing to burn. There was no lack of help, but all were helpless to do more than that. Only the things most needful, such as beds and eatables, were saved. One lady begged so for her piano that was got out on the porch and there left to burn. Cows ran bellowing through the streets. Chickens flew out from yards and fell in the streets with their feathers scorching on them. A dog with his bushy tail on fire ran howling through, turning to snap at the fire as he ran. There is no use trying to tell about the sights I saw and the sounds of distress I heard. It cannot be told and could hardly be believed if it were told. Crowds of people, men, women, children, and soldiers, were running with all they could carry, when the heat would become unbearable, and dropping all, they would flee for their lives, leaving everything but their bodies to burn. Over the levee the sights and sounds were harrowing. Thousands of people, mostly women, children and old men, were wringing their hands as they stood by the little piles of what was left of all their worldly possessions. Thieves were everywhere, and some of them were soldiers. I saw one knocked down and left in the street, who had his arms full of stolen articles. The provost guards were everywhere, and, I am told, shot down everyone caught spreading the fire or stealing. Nearly all buildings were of wood; great patches of burning roofs would sail away, to drop and start a new fire. By noon the thickly settled portion of Alexandria was a smoking ruin. The thousands of beautiful shade trees were as bare as in winter, and those that stood nearest the houses were themselves burning. An attempt was made to save one section by blowing up a church that stood [the Episcopal church] in an open space, but the fuse went out and the powder did not explode until the building burned down to it, and then scattered the fire instead of stopping it, making the destruction more complete than if nothing of the kind had been attempted.

A correspondent for the St. Louis Republican was a witness of the conflagration too and filed his report about the burning of Alexandria, which was picked up and reprinted in the Richmond Enquirer.

When all the gunboats were over the falls, and the order to evacuate was promulgated, and the army nearly all on the march, some of our soldiers—both white and black—as if by general understanding, set fire to the city in nearly every part, almost simultaneously. The flames spread rapidly, increased by a heavy wind. Most of the houses were of wooden structure and were soon devoured by the flames.

Alexandria was a town of between four and five thousand inhabitants. All of the city north of the railroad was swept from the face of the earth in a few hours, not a building left. About nine-tenths of the town was consumed, comprising all the entire business district and all of the city’s finest residences, along with the Ice House Hotel, the Court House, all the churches except the Catholic, and a number of livery stables.

End of a Failed Campaign

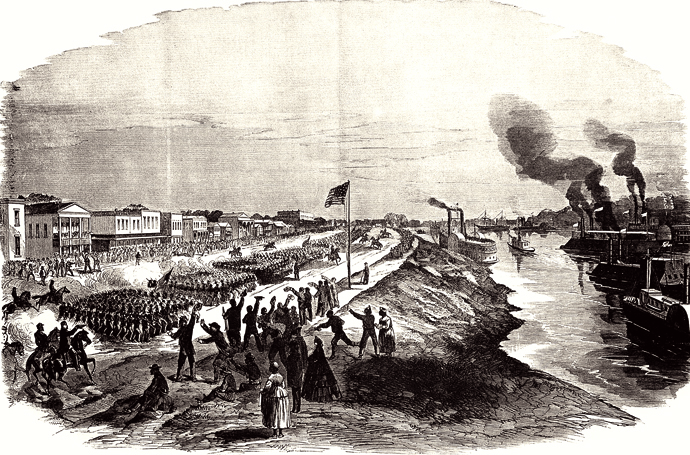

The burning of Alexandria occurred during the final days of the Red River campaign. Nathaniel P. Banks, Union commander in the Department of the Gulf, had begun planning for an expedition up the Red River in late December 1863. The plan of operation called for Banks to march north along the Bayou Teche through Vermillionville [Lafayette] and Opelousas to Alexandria with between 15,000 to 18,000 men. A second force of 10,000 men under Brigadier General A. J. Smith was detached from Major General William T. Sherman’s army at Vicksburg. These troops were to travel by transport down the Mississippi River and then up the Red River to Alexandria, where they would join Banks for the march on Shreveport. Meanwhile, Major General Frederick Steele was ordered to move his troops from their positions in central Arkansas in order to link up with Banks and Smith at or near Shreveport. Finally, a fourth Union force consisting of David Dixon Porter with his fleet of gunboats would operate on the Red River itself.

Color reproduction of an 1864 map of the Red River Campaign of the Civil War by Richard M. Venable. Library of Congress.

Banks, Smith, and Porter met at Alexandria and continued their advance toward Shreveport. The Confederate army under the command of Richard Taylor skirmished with Banks’s men as they advanced along the south bank of the Red River. For reasons that have never been satisfactorily explained, Banks ordered his men at Grand Ecore to take a road that swung away from the river, thus forfeiting the support of Porter’s gunboats. This route passed through an important crossroad south of Shreveport at Mansfield. Banks’s army was strung out on a narrow road and flanked by dense pine forests as it moved north. At Mansfield, Taylor struck the head of the column on April 8 and sent it reeling in disorder. However, the Union army recouped and dug in at Pleasant Hill, where they successfully fended off a fierce Confederate assault the next day. An aggressive commander would have resumed his advance on Shreveport, but Banks had given up, and he ordered a retreat, first to Grand Ecore, and eventually all the way back to Alexandria. Although Banks had no way of knowing it at the time, Steele had encountered problems of his own and had aborted his part in the campaign as well.

There is no doubt that Banks would have continued his retreat to the Mississippi River if he could, but Porter’s fleet of gunboats was trapped by the falls just above Alexandria. There had been a dry spell, and the Red River had continued to fall. Historians have assumed that it was the dry weather that had caused the low water. But ground-breaking research by Gary Joiner has discovered that the Confederates were actually diverting water from the Red River into a bayou south of Shreveport. In fact, the Confederate engineers had blown a dam, which allowed the diversion to occur almost a week before the Union army had started for Shreveport from Alexandria. The dry weather helped, but Porter’s gunboats were trapped by the premeditated resourcefulness of Confederate engineers.

The Union army had engineers too, and one of their best, Colonel Joseph Bailey, oversaw the construction of wing dams that channeled the river and raised the water level. It was difficult, frustrating work, especially when one of the dams gave way before the boats could pass over the falls. But on May 13, the dams were complete, and all of Porter’s gunboats, even the heaviest, successfully shot the gap. Within two days, the Union navy was back in the waters of the Mississippi River while the army trudged overland on its way to safety.

Seeking the Truth

The Red River campaign with the concomitant destruction of property and lives became the subject of two official investigations — one Union, the other Confederate. The Union investigation was headed by the Joint Committee of the Conduct of the War in the United States Congress. The Joint Committee had plenty to investigate because the whole affair had been, as William T. Sherman put it, “One damn blunder from beginning to end.” However, the burning of Alexandria did not figure prominently in the proceedings. In fact, the subject came up only once during the questioning of witnesses.

On December 14, 1864, General Banks appeared before the Joint Committee to provide his explanation as to why things had gone wrong. He referred to the burning of Alexandria only once during the many hours he was on the stand, and then it was only as an afterthought.

One of the members of the Joint Committee, Mr. Odell, asked General Banks, “Of what did that property [that you confiscated for use by the army] consist?

Banks answered, “Of cotton and sugar, forage, horses, mules, etc.”

Odell asked, “What was about the amount of that property?”

Banks answered, “That I cannot tell. Colonel S. B. Hollabird, the quartermaster of the department of the Gulf, can supply that information.”

Odell persisted in his line of questioning. “Did it embrace any furniture, such as pianos, looking-glasses, etc?”

Banks answered, “No, sir, not a solitary thing in the way of private furniture was authorized to be taken. If it was taken it was stolen. If a soldier was seen with a rocking-chair or a looking-glass it was taken from him and sent back. There was a great deal of property destroyed, and a portion of the town of Alexandria was burned. When the navy began to seize the cotton the enemy began to burn it. Below Alexandria nothing was burned, but above Alexandria pretty much all of the cotton was burned. When we returned to Alexandria it was understood that the town would be fired. I did not see any necessity for firing the town. I knew there were a great many Union people there, and I gave instructions to General C.C. Grover to provide a guard for its protection at the time of our leaving it, which he did. But on the morning of our departure, or on the day we left, a fire broke out in the attic of one of the buildings on the levee. I was there at the moment the fire broke out. Some soldiers or refugees had been quartered there, and it was not in human power to prevent their setting their place on fire when they left. The colored engineers and other troops were sent for, to the number of a thousand or more, and they did everything that it was possible to do to extinguish the flames; but everything was so dry, there having been but little rain for many months, that a great part of the town was destroyed.”

In the 400 pages of the Joint Committee’s printed report, there is only one other reference to the burning of Alexandria, and that was a summary of Banks’s testimony. The fact that Union authorities treated the burning of Alexandria as an afterthought can be verified by searching the Official Records of the War of the Rebellion, a 128-volume compilation of documents related to every aspect of the Civil War. Other than the summary of Banks’s testimony, which appeared in the Official Records because he also submitted it to Secretary of War, only one other reference to the incident is noted, and it was from a Confederate officer, Lieutenant Edward Cunningham, who was serving as an aide-de-camp to Lieutenant General E. Kirby Smith. On June 27, 1864, Lieutenant Cunningham wrote his uncle in Lynchburg, Virginia. For some reason, this letter found its way in to the Official Records, possibly because it was one of the few comprehensive accounts of the campaign from the Confederate perspective. “The Yankees left Alexandria about May [13], after burning two-thirds of the town,” he wrote. “Whether it was their intention to burn the whole place, or only some of the public buildings, warehouses, &c., does not clearly appear. My opinion is they did not intend total destruction. The wind was very high and the fire could not be managed.”

It would seem that the official position on the burning of Alexandria, as far as Union authorities were concerned, was that there was a single fire, started by persons unknown, which had burned out of control as a result of a high wind.

If the Union authorities essentially ignored the burning of Alexandria, the Confederate authorities did not, and they did not accept the theory that the fire had a single point of origin.

In June 1864, Confederate governor of Louisiana, Henry Watkins Allen, appointed seven commissioners to collect testimony concerning the conduct of the Union army during its 1863 and 1864 campaigns in Louisiana. His desire was “to obtain for publication and historical record a careful, accurate statement of the atrocities and barbarities committed by the Federal officers, troops, and camp followers during their late invasion of Western Louisiana.” By April 1865, three of the seven commissioners had submitted their reports, and Governor Allen had them printed in Shreveport. The resulting monograph was one of the last imprints to be published in the Confederacy.

Judge Thomas C. Manning was the commissioner for Rapides Parish, and much of the testimony he collected concerned the burning of Alexandria. One of the most objective witnesses who came before him was Jacob Walker, a merchant whose store faced the river on Front Street. He provided his testimony on June 27, just six weeks after the event.

I have resided in this town (Alexandria) twenty-four years, and am a native of Germany — am fifty years old. This town was fired on the morning of Friday, May 13th, between 8 and 9 o’clock, A.M. Several Yankee soldiers broke into the store on Front Street next to mine and pilfered the tobacco, sugar, and lard, which were the sole contents. While the party were below [in the building] another set went into the second story, and immediately afterwards the house commenced burning. The fire was applied in the second story. While this was going on I was standing on the levee which runs along one side of the street, immediately opposite the store, and about eighty feet from it. This was the commencement of the conflagration. The store and those on either side adjoining were wooden buildings.

Another witness who appeared before Judge Manning was also a long-time resident of Alexandria, Giles C. Smith.

I have resided in this town eighteen years. My residence was on Second Street, with one house (R. C. Hynson’s) intervening between it and the Episcopal Church. It was new, built entirely of brick, with slate roof and parapets. Hynson’s house had burned to the ground. It was of wood, about ninety feet from mine. My house had not caught fire; I had wet blankets on the side next to Hynson, and took out the window sashes, which were of wood.

Four or five officers came into the lower apartments and ordered my wife and family out. I immediately followed. One of them went into the rooms on one side of the passage and the other into the other side. There was a mattress in one room and the Yankee who went into that room walked up to it and, drawing his hand across it with a wide swoop, the mattress instantly caught fire, and the room was in a blaze. I did not see anything in his hand, and do not know what it was he had, but suppose it was turpentine that he threw upon the mattress, which was ignited by a Lucifer match. I seized the mattress and got it downstairs and in the street where it burned up.

But Giles Smith’s home did not escape the arsonists. A squad of Union soldiers visited his home again, and this time they did not leave until it was consumed by flames.

A local physician, Dr. J. P. Davidson, collaborated the testimony of both Jacob Walker and Giles Smith.

The fire was communicated to a building on Front Street, in a central part of the town — a strong north wind blowing at the time — and from the drought which had prevailed for some weeks, the flames spread rapidly from building to building. At the premises of Frozine, a free woman of color — below the origin of the fire and to the rear of it — men entered the yard with a tin bucket and mop, and sprinkled the fencing and out-buildings with a mixture of turpentine and camphene, saying that they “were preparing the place for Hell!” At several points where the progress of the fire was arrested by the inter-position of a brick edifice, similar means were resorted to — to continue the conflagration.

As Governor Watkins noted in the preface to the report, soldiers in the Union army accused of these atrocities did not have “the privilege of introducing evidence to explain, mitigate or rebut what will be published against them.” Thus, we will never know to what degree these accusations were based on actual occurrences. But one fact, one startling fact, remains beyond dispute. Most of Alexandria burned to the ground in a remarkably short period of time.

Orchestrated Arson

If the burning of Alexandria was the result of a concerted effort, who was responsible? It is fairly easy to dismiss the rumor that Jayhawkers did it. The testimony on both sides was unanimous that the fire started while Union troops were still in control of the town, and it is unlikely that the rag-tag collection of Confederate deserters and Union loyalists would have had the freedom to engage in acts of orchestrated arson. Rather, it would have had to have been a group of men with the discipline and authority to coordinate their actions and move unhindered through the streets of Alexandria. But who could they have been?

The order of march out of town may provide a clue. The first to leave was the Thirteenth Army Corps, a unit that had fought at Vicksburg but that had been posted to New Orleans in August 1863. Next on the road was the Nineteenth Army Corps, Banks’s old command consisting of regiments from New York and New England. The final unit to pull out was the contingent from Sherman’s army under the command of A.J. Smith. They were the men who would have had the opportunity to cause some mischief as the army withdrew.

The Union soldiers were already familiar with the concept of a “hard war.” Everyone knows about Sherman’s march through Georgia and the destruction to that state he caused. But many people have never heard of the Meridian expedition, a action that Margie Bearss called “Sherman’s Forgotten Campaign.” (A recently released book has just been published on this campaign: Sherman’s Mississippi Campaign by Buck Foster.)

After the fall of Vicksburg, Grant’s large army was broken up: some of it going to New Orleans, some of it staying in Vicksburg, but most of it going to Chattanooga, Tennessee, to bolster sagging Union prospects there after the Battle of Chickamauga. Grant went to Tennessee, and Sherman assumed command of the troops in Vicksburg, his first independent command. Recognizing the importance of the rail junction at Meridian, Mississippi, and the arsenal at Selma, Alabama, Sherman decided to drive due east from Vicksburg through Jackson to Meridian, and from there to Selma, if a large force of Union cavalry from Tennessee were able to link up with him in Meridian. The expedition started out in early February 1864 and made it to Meridian with little or no opposition, destroying property and tearing up track along the way. After Sherman reached Meridian he learned that Nathan Bedford Forrest had routed the Union cavalry from Tennessee at Okolona and he satisfied himself with destroying the railroad for miles in every direction. Sherman then marched back to Vicksburg by a different but parallel route in order to inflict more punishment of the state’s population.

The Meridian expedition was a tune-up for his march through Georgia nine months later. “I got back from Meridian yesterday, and am now hurrying down to see General Banks as to some of the details of the expedition against Shreveport,” he wrote on February 29:

My movement to Meridian stampeded all Alabama. [Lieutenant General Leonidas] Polk retreated across the Tombigbee and left me to break railroad and smash things at pleasure, and I think it is well done. Weather and everything favored me, and I do not regret that the enemy spared me battle at so great a distance out from the river. It would have been terrible to have been encumbered with hundreds of wounded. Our loss was trifling, and we broke absolutely and effectually a full hundred miles of railroad at and around Meridian. No car can pass through that place this campaign. We lived off the country and made a swath of desolation 50 miles broad across the State of Mississippi, which the present generation will not forget.

There were twenty-two regiments in the contingent from Sherman’s army commanded by A. J. Smith in the Red River campaign. Nineteen of the twenty-two as well as their commander had returned from the Meridian expedition less than two weeks before they boarded transports in Vicksburg. Apparently, these soldiers brought their newly-acquired, hard attitude toward war with them to Louisiana. “The inhabitants hereabout are pretty tolerably frightened,” Brigadier General T. Kilby Smith, one of A. J. Smith’s division commanders and a veteran of the Meridian expedition, wrote to his mother from Alexandria during the trip up river. “Our Western troops are tired of shilly shally, and this year will deal their blows very heavily. The people will now be terribly scourged. Quick, sharp, decisive, or if not decisive, staggering blows will soon show them that we mean business.” If Kilby Smith and his men felt that way before the battles at Mansfield and Pleasant Hill, we can only imagine how they felt after the retreat to Alexandria.

Mutiny in the Ranks

J. Smith’s troops had the prerequisites needed to burn Alexandria — a good opportunity and a bad attitude, but these two factors alone can not excuse what happened. Where was the military discipline that should have kept these men in line? During the Red River campaign they were not serving under Sherman, and Banks had issued a specific order against the wanton destruction of Alexandria. “You are hereby directed to detail a force of 500 men from your command to protect the town of Alexandria when the army shall leave its present position, and to bring up the rear guard, taking every precaution possible to [prevent] any conflagration or other act which would give notice to the enemy of the movements of the army,” Banks had informed his Chief of Cavalry on May 9th. “Officers of responsibility and character should be selected for this duty,” he added, “and they should be notified that the will be held responsible for the acts of the men under their command. They will occupy the town until all persons connected with the army have left it, and then cover the rear of the column on its march.”

Black-and-white reproduction of a photograph of Union Major General Nathaniel Banks. Library of Congress.

Banks’s order was clear and precise, but, apparently, it had no effect. The main reason for the lapse was that Banks left town long before the rest of the army pulled out, and his absence was compounded by another development that did not bode well for Alexandria, the loss of Banks’s ability to command. The humiliating end to a campaign that began with such high hopes had angered and demoralized the men, and now they hooted at Banks behind his back when he rode by. For his part, Banks had lost his composure, and the men were quick to notice. “Gen. Banks is awfully scared,” a Union soldier wrote to his sister from Alexandria. The erosion of Banks’s authority was especially true among the officers and men in the contingent from Sherman’s army. A. J. Smith had chaffed under Banks’s direction throughout the campaign, but Banks’s control over Smith and his men had evaporated when Banks had issued orders at Grand Ecore to continue the retreat to Alexandria.

When Smith heard of Banks’s decision, he could not believe that the army was going to retreat again. He was accustomed to serving under Grant and Sherman and could not stomach Banks’s timidity. Smith found himself becoming more and more angry, and one evening he encountered two of Banks’s division commanders, Major General William B. Franklin and Brigadier General William H. Emory, along with some officers of lower rank. Smith voiced his criticism of Banks loudly, so much so that one of the staff officers felt obliged to leave the tent. After the officer had gone, Smith made a startling suggestion. “Franklin,” he said, “if you will take command of the army, I will furnish a guard and put General Banks in arrest and send him to New Orleans.” Emory, who was seated nearby, jumped up and exclaimed, “By God, gentlemen, this is mutiny,” and strode out of the tent. And so it was.

Although A. J. Smith dropped the idea of sending Banks back to New Orleans under arrest, the incident at Grand Ecore made it clear that Banks had lost the confidence of his generals, particularly A. J. Smith. Furthermore, Smith’s men were only a few days away from rejoining their old command in Vicksburg when they marched out of Alexandria. A combination of factors — exposure to fighting a “hard war” while serving under Sherman during the Meridian expedition, a humiliating defeat at the hands of an inferior Confederate force at Mansfield, the uncalled for retreat despite a victory at Pleasant Hill, and the lack of a command presence — resulted in an ill-tempered, ill-disciplined band of soldiers with larceny in their hands and arson in their hearts. The resultant insubord-ination fell heavily on the citizens of Alexandria, but A. J. Smith’s men had not acted alone. Just as dry weather aided the Confederates when they diverted water from the Red River, almost accomplishing one the grandest military coups of the entire war, high wind blowing from the north assisted these angry men in carrying out the most senseless act of incendiarism Louisiana has ever seen.

————–

James G. Hollandsworth, Jr., is the Associate Provost and Professor of Psychology at the University of Southern Mississippi. After a successful career as a psychologist, during which he authored two books on the physiological bases of human behavior and mental disorders, Hollandsworth rediscovered his orginal interest in American history and now spends much of his free time pursuing topics related to the Civil War in Louisiana and Mississippi.