Sound Advice

Bust Fund Babies

The Grateful Dead got a sour reception in New Orleans

Published: December 1, 2019

Last Updated: August 16, 2020

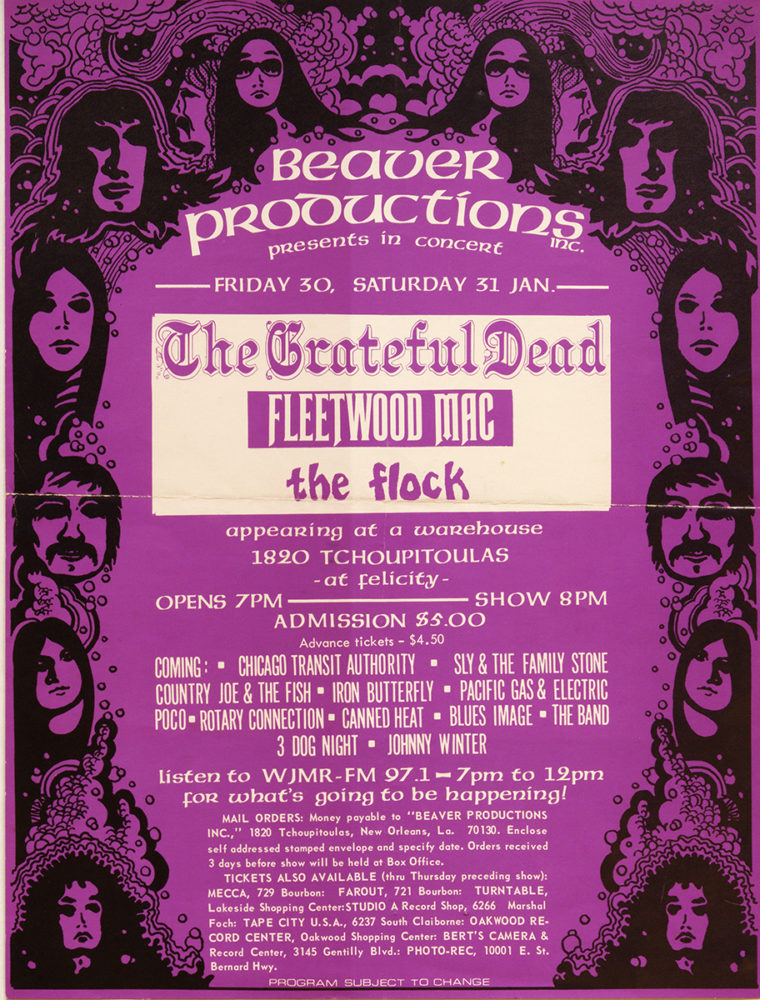

The Historic New Orleans Collection

A promotional poster for the fateful shows.

An ode to life on the road in the hip scene, “Truckin’” appears on 1970’s American Beauty. Taking into account that the Grateful Dead are best experienced live or via recordings of its live shows, a massive body of work with entries both official and bootlegged, which fans carefully preserve and trade and debate and celebrate, it’s still probably fair to assert that the American Beauty album is the most common entry point to the music of the Dead, and “Truckin’” is one of its most beloved cuts. (It’s also the source of the lyric “What a long, strange trip it’s been,” widely quoted in writing about the band, writing about the ’60s, and senior yearbook pages.)

On the very last days of January 1970, the Grateful Dead were booked to play the opening weekend of a brand-new New Orleans nightclub called A Warehouse, located at 1820 Tchoupitoulas Street. It was a two-night stand in the thick of Carnival season with Fleetwood Mac opening, plus a Chicago band called the Flock. Doors were at 7, show at 8, with tickets $5 at the door or $4.50 in advance by mail.

The band members were staying at the Royal Sonesta Hotel, at 300 Bourbon Street. Downtown New Orleans was a particularly interesting place that Carnival season, according to Mark Duffy, whose late father Earl was, in 1970, the Royal Sonesta’s general manager. 1969’s Easy Rider—with its scenes of the hippie bikers played by Dennis Hopper and Peter Fonda roaming the Quarter during the holiday—had served as an advertisement to the counterculture that Mardi Gras in New Orleans was the place to be. The neighborhood was overrun with flower children sleeping in the doorways and in Jackson Square. “You couldn’t walk ten feet without getting hit up for spare change,” he recalled. Hotel and restaurant stakeholders like his dad were nonplussed. (Duffy himself was seventeen in 1970 and more sympathetic to the hippies). The Grateful Dead, of course, were paying guests, but their behavior still raised eyebrows.

“Guests had complained about them,” said Duffy. “There were reports of guests getting into an elevator and they’d run into a musician or a roadie, and [the musician or roadie would] do something like belch, loudly.”

Police, too, were actively suspicious of out-of-town hippies, whether they were sleeping in streets or suites. A few months earlier, the Jefferson Airplane, another Bay Area psychedelic rock band, had been busted for marijuana possession by local police—also at the Royal Sonesta, according to a Rolling Stone report from March 1970—after a performance at the St. Bernard Civic Auditorium.

And in the early morning hours of Saturday, January 31, 1970, they came for the Grateful Dead. The front-page story in the February 1 edition of the Times-Picayune (slightly below a report on the previous night’s Mardi Gras parades) was headlined “Drug Raid Nets 19 in French Quarter: Rock Musicians, ‘King of Acid’ Arrested.” Guitarist Bob Weir, bassist Phil Lesh, and drummer Bill Kreutzmann were named in the paper as among those caught (though Kreutzmann’s surname was misspelled as “Krentzmann.”) So were then-manager John McIntire, crew members Lawrence “Ramrod” Shurtliff and Donald “Rex” Jackson, and a person recorded as “Summer Wind, spiritual advisor to the Grateful Dead”—although, according to Dennis McNally’s definitive Dead biography A Long Strange Trip, this was percussionist Mickey Hart, who for some reason had a piece of identification with that name and title.

Jerry Garcia apparently almost made it out; the raid was in progress when he returned to room 2186 around 5 a.m. and caught sight, through the open door, of NOPD officers rifling through his things. He kept strolling and got to the lobby, where according to the original police report, he was “observed” by federal narcotics agents and detained.

The band put the take from the Warehouse shows toward bail for the whole group of arrestees and added a third concert as a benefit for a “bust fund,” apparently expecting more out-of-town bands to run into the same problem.

The “King of Acid” referenced in the paper was Augustus Owsley Stanley III, who would in a few years build the band’s famous Wall of Sound, a massively powerful and distortion-free public-address system. Besides his skills as a sound engineer, Owsley, also known as “Bear,” was a talented illicit chemist who had developed a reputation in hippie circles for making LSD that was as clean and strong as the output from his sound system would be. (A few months after the Dead’s bust, Jefferson Airplane would release the single “Mexico,” with the lyrics “You’re a legend, Owsley, / for your righteous dope.”) The charges for band, crew, and friends variously included possession of LSD, barbiturates, marijuana, amphetamines, narcotics, and in Owsley’s case, “dangerous non-narcotics.”

As stated in the police report, the NOPD and the Federal Bureau of Narcotics had received three separate tips about the band a few days before the Warehouse shows. Two were credited to confidential informants who spoke with officers, and one to an anonymous letter that read in part: “The dead have been boasting on the coast that they are going to turn New Orleans ON because their friends, the Jefferson Airplane got busted here. I cannot tell you my name because they would hurt me. I used to date one of them.”

Officers arrived at the hotel at 9:30 p.m. with a warrant, and they confirmed which rooms belonged to the band with hotel security. According to the report, by about 10:45 p.m., they saw and smelled marijuana smoke coming from under one of the doors and took that as their cue to go in.

Earl Duffy, his son said, had gotten a courtesy tip himself from NOPD that the raid—far more unwelcome to a hotel manager than elevator belching—was coming, but all he could do was wait for it. The band put the take from the Warehouse shows toward bail for the whole group of arrestees and added a third concert as a benefit for a “bust fund,” apparently expecting more out-of-town bands to run into the same problem. Lenny Hart, another Dead manager, told Rolling Stone later that the group had been careful not to keep illicit drugs on them and that what was found had, he suspected, been planted—hence the “Truckin’” lyric “set up, like a bowling pin.”

“New Orleans police just aren’t welcoming rock bands,” Hart told the magazine. “Any group that goes there should be awfully careful.”

The band members were able to get their charges dismissed—according to A Long Strange Trip, due in part to some backchannel dealing that included a promise to stay out of New Orleans. (Which they kept: the Dead didn’t return until 1980—and after that, they only played four shows total in New Orleans over the fifteen years remaining before Jerry Garcia’s death.)

It was at some point in the ’90s, Mark Duffy recalled, that his father—who had gone on to become the first president of the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Foundation’s board of directors—heard “Truckin’” for the first time. “He was in his seventies and retired, and we were in Key Biscayne and it came on the radio,” said Mark. “I said, hey, that’s your song. I told him it had been a big cultural hit, and he got a big charge out of that.”

Alison Fensterstock’s first Grateful Dead show was at Madison Square Garden in 1992.

Sound Advice is funded in part by a grant from the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Foundation.