Lost Lit

Can You Hear Me, Sergeant Blue?

A hard-boiled detective in an intergalactic world

Published: December 3, 2018

Last Updated: June 12, 2023

John W. Knott Jr., Bookseller

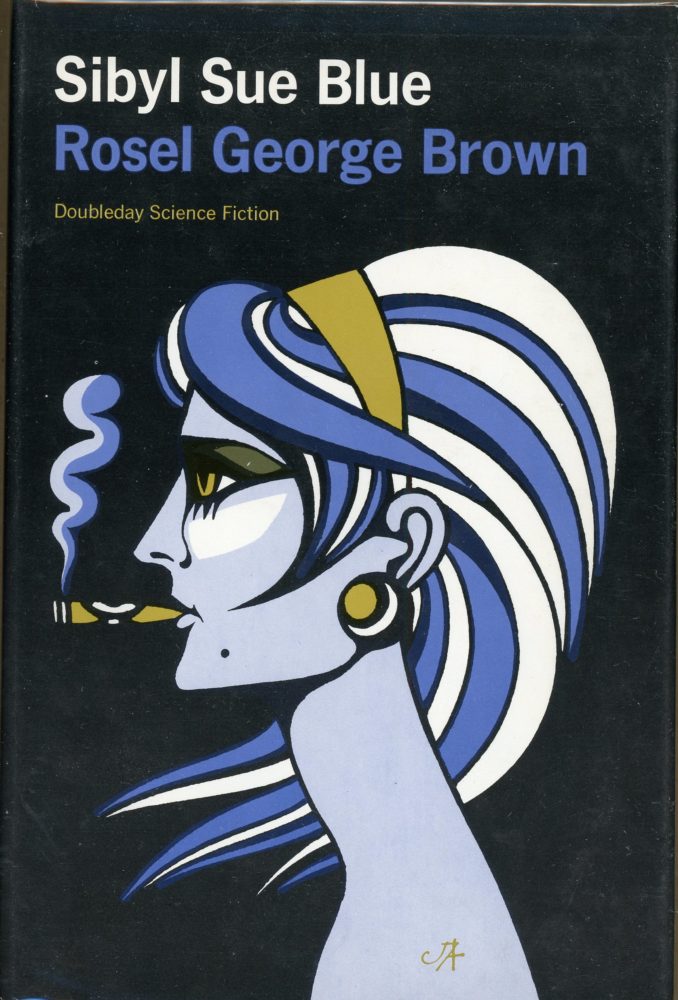

Original cover art for Sibyl Sue Blue by Rosel George Brown, Doubleday, 1966.

Take Ignatius Reilly and the Dunces krewe, for example.

I recognize each and every one of them from my walks around the French Quarter.

Lestat?

Reminds me of an old college roommate who never slept.

Edna Pontellier?

I’ve loved a couple awakened women just like her.

Binx Bolling?

Heck, I am Binx Bolling (with apologies to all the Ednas out there).

So please allow me to introduce Sibyl Sue Blue. That’s police Sergeant Sibyl Sue Blue to you: interstellar femme fatale, star of an eponymous science fiction novel by Rosel George Brown, and, quite possibly, the most unorthodox New Orleans literary creation ever conceived.

When we first meet Sergeant Blue, she’s pummeling a drugged-out, pistol-packing Centaurian with her handbag on a desolate downtown sidewalk. Two pages later, she’s attacked in a bar by a second Centaurian, whom she quickly dispatches with a stiletto heel to the forehead. Spiky-toothed, scaly reptilians from the planet Centaur, they’re an ordinarily peaceful alien race, but Sergeant Blue has a hunch that these particularly menacing extraterrestrials are connected to a spate of murdered human teenagers.

So begins Rosel George Brown’s hardboiled, spaced-out sex romp of a novel, published by Doubleday’s Science Fiction imprint in 1966. Born in New Orleans and educated at Newcomb College, Brown later earned an MA in Ancient Greek from the University of Minnesota before resettling back home with her husband, a Tulane history professor. Beginning in 1958, she began publishing short stories in pulp fantasy magazines with names like Galaxy, Fantastic Universe, and If, which were later collected in her first book, A Handful of Time (1963). Almost from the beginning, her fiction featured fierce, sex-positive women who tiptoed the razor’s edge between female empowerment and fanboy fetishization. (In “Step IV,” for instance, published in Amazing Stories in 1960 and readable online, a male Earthling crash-lands on an all-female planet, where he meets the alluring Juba. The story follows Juba’s reluctant advancement through the four steps culturally required to keep her planet safe from the invasion of more men: communication, seduction, intercourse, and, finally, murder.)

Despite its local roots, there’s nothing particularly New Orleans-y about Sibyl Sue Blue. Its cast of characters are not appropriated from French Quarter sidewalks. Though this is the future—the year 1990 to be exact—there’s no references to freeze-dried space gumbo, or any ongoing pothole problem. Brown did set her novel though in the spaceport city of Hammond. Not the Tangipahoa Parish Hammond of the future, per se, but a dystopian, Blade Runner-y, strawberryless Hammond that exists—fingers crossed—on some alternative Earth.

Brown’s novel is, more than a product of place, an artifact of its time. Sibyl Sue Blue is “the swingingest mama since—well, since,” one contemporary critic wrote. “Under all the froth and fun and furious action, there is more acute comment on contemporary society than you are likely to find in any half dozen deadly serious social novels.” She is a 1960s feminist, a forty-year-old single mom who smokes cigars, knocks back countless gin and gingers, dresses like a Cosmopolitan model, calls her male colleagues “honey,” and has sex with whomever she pleases. Like her creator, she’s a scholar of Greek history who reads Thucydides before bed. She’s witty, a deep-space Helen Gurley Brown. “What was he like with sex?” Blue wonders during a dinner date with a man whose appetite doesn’t equal her own. “Did he sort of push it about on his plate, too?”

And though she’s quick with a punch, Blue is an egalitarian, a civil-rights idealist. When a superior officer dismisses Earth’s resident alien population as “Dirty Centaurians,” our hero takes a page from the anti-colonialist handbook. “You are prejudiced and I hope you know it,” Blue tells her boss. “Thirty years ago . . . everybody knocked each other out to proclaim the glories of Centaurian culture and to wonder at the discovery of another humanoid civilization. Now these glorious Centaurians live in a ghetto.”

Though this is the future—the year 1990 to be exact—there’s no references to freeze-dried space gumbo, or any ongoing pothole problem.

This being the 1960s, there’s also a healthy dose of psychedelics. The murders, Blue quickly surmises, are linked by unknowing teenagers getting high on a psychotropic from the planet Radix, the same ominous green orb that swallowed her husband ten years prior. She does what any self-respecting spiritual seeker would do: lights a match and tokes up. Stoned on what amounts to the galaxy’s most potent weed, Blue merges with Radix’s planetary consciousness, dreaming vivid visions of “gliding green images, vegetable thoughts and the voice of Kenneth calling through green aisles and always forever distant.”

Naturally, Blue endeavors to hitchhike to the source, Radix, where she hopes not only to solve her case, but also to find her missing husband and bed down with Stuart Grant, a wealthy playboy and the captain of this expedition. “Can you smoke cigars on spaceships?” she wonders as she boards with a bag of sultry cosmic outfits in tow.

Will psychedelic flashbacks incapacitate Sibyl Sue Blue before she unravels the mystery of the teenage murders? Is Kenneth still alive? Why does playboy Grant want to travel to Radix? Why are there Centaurians chained in the cargo hold of his spaceship? And, most importantly, is he a good lay?

Turn on, tune in, and drop out to find out . . .

The novel would be reprinted in a pocket-sized paperback under a revised name, Galactic Sibyl Sue Blue, in 1968, the same year that the carbon copy that is Jane Fonda’s Barbarella hit cinemas. A Sergeant Blue sequel, The Waters of Centaurus, appeared two years later. Tragically, Rosel George Brown didn’t live to see the follow-up published. In 1967, she succumbed to lymphoma at the age of forty-one. Speculative fiction fans have since worked to elevate Brown’s status as not only an early female genre writer but one of its first feminist champions.

Despite being an atypical New Orleans character, Sibyl Sue Blue will always belong to the city, as much as she belongs to the cosmos.

Rien Fertel’s newest book, Southern Rock Opera, is about a road trip inspired by an album about one of history’s most famous airplane crashes.