Winter 1997

Congo Square: La Place Publique

The African American culture nurtured in New Orleans’ Congo Square was, and is, unlike any other

Published: February 16, 2016

Last Updated: January 15, 2019

Taking account not only of the musical aspects of the square but of a number of non-musical aspects of its history gives Congo Square a special importance. The music-making in the square came to rival the highly romanticized “Quadroon Balls” as antebellum New Orleans’ most celebrated public black institution. At the same time, the square’s activities constituted, in a larger sense, a citywide institution that involved, in one way or another, and for over a century, a large number of New Orleanians, black and white.

When its unusual origins and a lifespan far longer than hitherto supposed are taken into account, Congo Square becomes uniquely significant. Its story not only bears upon the development of jazz and the history of black New Orleans, but adds to our understanding of the physical growth of the early city, its economic development, and the formation of its social and ethnic configuration, as well as the evolution of its celebrated public culture. Perhaps most importantly, it identifies a point of origin, indeed probably the major point of origin, of modern American dance.

As historian and literary critic Arlin Turner said in his prizewinning study of George W. Cable: “No spot in New Orleans could better…suggest the history of the lower half of the population, and through contrasts the upper half as well.”

Congo Square always remained different from New Orleans’ other squares because it was never really laid out by the city’s planners as a public square. Instead, it took its shape gradually and informally out of peculiarly New Orleanian circumstances. It was, in its origins as in its development, always of the people, an aspect of its character that was recognized when the spot was, for a brief time after the Louisiana Purchase (1803), officially designated La Place Publique.

Congo Square originated not in the early American decades of New Orleans’ history, but nearly a hundred years before, in the early decades of its French colonial period, and not as a spot where black New Orleanians gathered to dance, play, and sing, but as one of the city’s public markets. The famous dancing, playing, and singing represented byproducts of the square’s market function.

It was, in its origins as in its development, always of the people, an aspect of its character that was recognized when the spot was, for a brief time after the Louisiana Purchase, officially designated La Place Publique.

“Free Days”

In 1721, twenty-two years after its founding in 1699, France’s Louisiana colony was ensnared in complications following the collapse of the Company of the Indies, the second of the two proprietors that held the colony between 1712 and 1731. The financial collapse of the company cut off not only food imports but virtually all capital supplies. Hard-pressed planters could not even afford to feed their slaves and, in desperation, moved to make their slaves more nearly self-sufficient. They began to assign slaves individual parcels of land on which to grow their own food, as well as sale crops.

Moreover, the planters began to see advantages for themselves in abiding by article five of the Code N0ir, a provision hitherto honored more in its breach than in its observance. That particular article exempted slaves from forced labor on Sundays and religious holidays. On those “free days,” which shortly came to include Saturday afternoons as well, slaves could hire themselves out for wages or take their surplus products–not only food stuffs and cash crops they had grown on their plots, but gleanings of nuts and berries from the woods as well as fish and game from the swamps–into town and sell them. With the proceeds they could buy many of their own necessities, including articles of clothing.

Once established, the recognition of slaves’ rights to free days continued. These free days came to be recognized even without the necessity of formal written permission to work for others or themselves on those days.

There was, of course, nothing unique about Louisiana’s slaves acting as merchants or being free to labor on Sundays. Slaves commonly did vending in South Carolina’s low-country, for example, and the Sabbath was respected as a non-work day for slaves throughout the American South. What made French Louisiana different was that slaves there were recognized early on as having the right to use their free time virtually as they saw fit, with little or no supervision. Such a conception, much less such a practice, never prevailed anywhere else in the South.

At first, and for quite a number of years, only a handful of slave peddlers occasionally sold goods up and down New Orleans’ few short streets and along its riverfront, which served as the city’s main food market. The tiny town’s population remained too small to have supported more. But as New Orleans’s population grew, the vendors increased both their numbers and the regularity of their operations. In time, a number of slave merchants began to gather on Sundays at a certain spot and spread their wares on the open ground, thereby creating a regularly scheduled, stationary market of their own.

The market may have begun to take shape as early as the latter 1730s, but more likely in the late 1740s or the 1750s, by which time New Orleans’ population approached 2,000.

The open ground upon which the slave vendors spread their wares and set up their market stalls stretched along the edge of the City Commons at the end of Orleans Street, just beyond where it abutted the low earthen breastworks and borrow pit that formed the city’s limits and served as its primitive defense line.

By the last decade of French rule, the trading activities of slaves had come to form a significant feature of New Orleans’s mercantile life, one sufficiently profitable to excite the attention–and envy–of local retail merchants, who petitioned the local procurador, or attorney general, to be allowed, in spite of the law, to open their shops before and after divine services on Sundays in order to be able to sell goods to slaves.

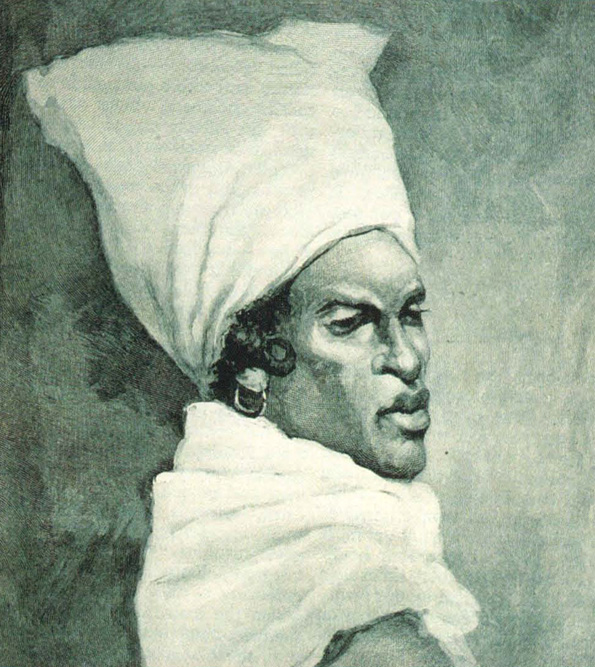

New Orleans’ women of African descent frequently wore traditional tignons as a headdress. Courtesy of The Historic New Orleans Collection

Changing Relationship

In 1760, midway through the French and Indian War, the local military engineers strengthened New Orleans’ defenses, a move that affected the market’s physical relationship to the city. The engineers completely redesigned the simple, low, straight-line breastworks on the back-of-town side of the city. They moved the whole defense wall several hundred feet into the City Commons, dug a moat to replace the shallow old borrow pit, raised a much higher breastwork mound, and built a palisade wall atop it. In three places they jutted the new breastworks and wall outward to form sharp, triangular bastions. The one at the end of Orleans Street they named Bastion Orleans.

In the enlarged area within the city that resulted from moving the defense wall outward, the engineers extended the old short streets and cut a new long street, Rampart, along the line where the old breastworks had run. In the remaining area they placed a new row of irregularly sized, trapezoidal blocks between the new street and the new wall. These were reserved for military purposes, but remained, for the rest of the French period, largely unused, wooded clumps. The thrusting out of the Bastion Orleans also brought the marketplace within the city’s walls. It remained open ground, lying across Rampart Street at the end of Orleans. There the slave merchants continued their market, on the very spot that, more than half a century later, would come to be known as New Orleans’ Congo Square.

Moreover, the planters began to see advantages for themselves in abiding by article five of the code noir, a provision hitherto honored more in its breach than in its observance. That particular article exempted slaves from forced labor on Sundays and religious holidays. On those “free days,” which shortly came to include Saturday afternoons as well, slaves could hire themselves out for wages or take their surplus products into town and sell them.

Three years after redesigning the city’s defenses, France lost the Seven-Year War with England, and with it, her entire North American empire. In 1763, England took Canada and Spain received France’s vast Louisiana territories. The change of administration in New Orleans, finally effected only at the end of 1769, and the ensuing thirty-five years of Spanish rule saw the local slaves’ market flourish. During that time New Orleans’ economy improved dramatically, and its population jumped from less than 3,000 to more than 8,000, and the market grew apace.

During the Spanish period a number of free colored vendors came to participate in the market alongside the bondmen. By and large, however, the market remained a slave activity.

The slave vendors suffered little from competition with the complex of centralized market facilities the Spanish constructed in three stages between 1779 and 1784, and rebuilt a number of times afterwards, finally to achieve the form known today as the French Market.

A Spanish city plan consisting of strengthening the defenses of New Orleans rebuilt and enlarged the Bastion Orleans, making it, in 1792, into Fort Ferdinand. The brick and frame edifice covered much of the ground where the market had been, but it displaced the vendors only slightly for they continued their sales at the foot of the fort’s gorge, on the esplanade that replaced portions of the old trapezoidal “military” blocks.

Spain returned the colony to France in 1803, and twenty one days later France handed it over to the United States. The Louisiana Purchase inaugurated the second and most important phase of Congo Square’s history.

A Public Place

The first American governor, William C.C. Claiborne, immediately ordered the removal of New Orleans’ old fortifications in order to open the city to its adjoining countryside in the typical U.S. fashion. As soon as the local population heard rumors of the removal project, they themselves largely dismantled the decayed palisade wall for firewood during the winter of 1804. What remained, including the three forts on the back side of town, Claiborne had pulled down early in 1805, leaving only the two forts on the river, which stood until 1808 and 1821.

The slave merchants continued their market on the enlarged open space created by the demolition of Fort St. Ferdinand. In 1812 the city authorities subdivided the old Commons and extended the city’s short streets across Rampart into the new area and cut a range of new long streets paralleling Rampart. In the process they reserved the spot where Fort St. Ferdinand had stood -the block bounded by Rampart, St. Claude, and St. Ann Streets on three sides, and by the Carondelet Canal turning basin on the fourth -for public use, as they did a number of other parcels of land in the new subdivision. Governor Claiborne had earlier explained to President Thomas Jefferson that preserving several open squares and laying out and improving several public walks would not only “beautify the town, but contribute greatly to the health and comfort of the inhabitants.”

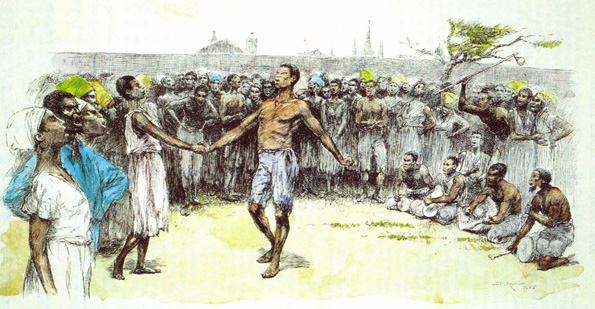

The bamboula and other African dances were performed at Congo Square on Sunday afternoons. Anglo-Protestant newcomers to New Orleans were both fascinated and appalled by the scene. Courtesy of The Historic New Orleans Collection

A number of the reserved spaces and promenades were planted with trees, sweet-smelling shrubs, and flowers. But the area of the city around the site of old Fort St. Ferdinand retained its commercial, transport, and service character. That site, lying next to the turning basin, always full of boats loaded with onions, turnips, collards, oysters, and shrimp, could never have been made into a leisure park. Instead the city fathers designated it Place Publique and left it a simple, open, grassy plain. But few would call the spot Place Publique for long. Circumstances gave rise to other, more popular, names.

For a number of years after the Louisiana Purchase, a certain Signore Gaetano “from Havana,” immortalized as “Monsieur Cayetano” in George Cable’s most famous short story, “Posson Jone’,” seasonally set up in the square his celebrated Congo Circus. Lafcadio Hearn said the circus became a “popular fixture” of New Orleans life, still remembered by New Orleanians when he was writing about it sixty years later.

In addition to a man who danced in a sack, one who danced on his hands, one who stood on the back of a galloping horse while drinking a glass of champagne, a “pretty young lady” bareback rider, and a monkey handler, the Congo Circus sported a tiny, four-horse carousel and featured fights between Signore Gaetano’s champion bear and tiger and local bulls and dogs.

The Place Publique’s long-remembered association with the Congo Circus and its still longer, and continuing, association with New Orleans’ old black community coalesced with its striking physical appearance -a starkly bare open field in the middle of an otherwise lushly overgrown city -to give rise to its famous name. While official documents continued to refer to it as Place Publique, the city’s white population increasingly called the spot Place du Cirque, Circus Park, and Circus Square. On the other hand, slaves and free people of color began to call the fairground “Congo Plain(s)” and “Congo Square.” Those names gained in popularity, especially as the square’s African dances, including one called the Congo, became occasions for outings by local residents as well as tourists. By 1850, the name “Congo Square” also began to appear in official records, along side “Circus Square.”

Governor Claiborne had earlier explained to President Thomas Jefferson that preserving several open squares and laying out and improving several public walks would not only “beautify the town, but contribute greatly to the health and comfort of the inhabitants.”

Then in the 1870s and 1880s, two things tipped the balance in favor of “Congo Plain(s)” and “Congo Square.” The name “Congo Square” became finally fixed when George Washington Cable, fascinated with the African component of the square’s history, used that name in his widely read articles, stories, and novels. Also, a multitude of guidebook and newspaper writers, in New Orleans for the Cotton Exposition of 1884-1885, picked up and used the term in their reports.

A Place of Liberty and Threat

The slave and free black vendors continued to set up at Congo Square on Sunday mornings to mingle with the crowds of other slaves and free blacks who gathered on Sunday afternoons for the square’s famous African dances. The Americans who flooded into New Orleans during the decades following the Purchase found themselves fascinated and not infrequently appalled by what they saw. The large number of free people of color, some bearing arms and most consorting intimately with slaves, who themselves appeared to enjoy a degree of freedom of movement and action unprecedented in the rest of the South, made many of the incoming Americans, including Governor Claiborne, extremely nervous. They had never seen anything like it. Nor had most seen anything like the way French Catholic New Orleans observed the Sabbath. After going to mass on Sunday morning, the Creoles made the rest of the day a festival, indulging themselves in public entertainment, going on outings and excursions, enjoying picnics and barbecues, shopping the street markets, and, on Sunday evenings, drinking and dancing. It struck the newcomers, mostly Anglo-Protestants accustomed to taking Sundays as days of grim abstinence and pious reflection, as near blasphemy.

The Sunday dances in Congo Square served, more than any other single facet of New Orleans life, to focus the Anglo-American concern and indignation. Benjamin Henry Latrobe’s reaction was typical. What he saw in the square in 1819, while in town to oversee the construction of the city’s waterworks, prompted him to write a long and altogether disapproving entry in his journal on the Creole mode of Sunday observance. He betrayed his amazement and apprehension at the sight of five or six hundred unsupervised slaves assembled for dancing when he added, in a tone of relief, “there was not the least disorder among the crowd, nor do I learn on inquiry, that these weekly meetings of Negroes have ever produced any mischief.” But at the same time, he, and observers like him, found themselves fascinated with the dancing, for they had never witnessed anything like it.

What they saw was not merely groups of slaves and free people of color dancing. Such was a common enough sight throughout the South. They saw something in New Orleans that had not been seen elsewhere in North America for nearly a century -native African music and dance still being performed. And that was what so fascinated the observers. Such African music and dance elsewhere had long before acculturated to Anglo-American norms, or, under pressure from Protestant preachers -black as well as white -had been all but completely eroded. “Only in Place Congo in New Orleans was the African tradition able to continue in the open,” concluded Dena J. Epstein from her masterful examination of antebellum black folk music.

African dances had been performed on the Congo Plains, as well as at other locations in the city, and on some plantations, since the importation of slaves began in the 1720s. But because of the Congo Plain’s long-standing role as a market -out of which the dancing grew from the way vendors and their friends wiled away the day between their occasional sales -that location became, and remained, a particular focal point for such dancing.

In addition to the various drums, gourds, sounding boxes, and banjo-like instruments that Latrobe saw, other observers noted the Congo Square musicians blowing cowhom hunting crooks and “quillpipes” made from reeds strung together like panpipes, playing marimbas, scraping the teeth of horses’ jawbones with sticks, and adopting European instruments such as violins, tambourines, triangles, and cremonas. They described the dancers as “dressed in a variety of wild and savage fashions … ornamented with a number of tails of the smaller wild beasts,” with “fringes, ribbons, little bells, and shells and balls, jingling and flirting about the performers’ legs and arms.”

One witness observed that the several clusters of onlookers, musicians and dancers in Congo Square represented, in the early decades, tribal groupings, “each nation taking their place in different parts of the square.”

“The Minahs,” he continued, “would not dance near the Congos, nor the Mandringos near the Gangas,” and often fights broke out between the groups, and some of the males, he said, still bore facial tattoos and had filed teeth.

The dances themselves, at least some of them, mounted, in an increasingly lascivious crescendo, from a slow, repetitious and grimly deliberate opening phase to a final frenzy of “fantastic leaps” in which “ecstasy rises to madness,” and finally, suddenly, the dancers fell, exhausted and unconscious, “foam on their lips,” and were “dragged out of the circle by their arms and legs” as new dancers took their place, the music never ceasing.

A rare winter storm draped Congo Square in snowfall. The sycamore trees were planted in 1845, one of many civic improvements that intentionally led to the demise of the squareas a site for African dancing. Courtesy of The Historic New Orleans Collection

The Loss of Tradition

Though the music and dance continued, the traditional Sunday market activities in Congo Square were seriously curtailed during the course of the 19th century. The opening of a centralized vegetable vending facility in the French Market complex in 1823 began to diminish the age-old marketing activities of Congo Square. Increased vending from market boats moored in the turning basin of the Carondelet Canal, which was deepened and widened, also cut into the slave vendors’ business. Competition from the huge Treme Market, which city authorities opened two blocks away in 1839—40, effectively ended the square’s history as a marketplace. Thenceforth, only a few street vendors remained in Congo Square to peddle gingerbread, rice cakes, and pralines to the Sunday afternoon crowds. At the same time, the 1834 construction of a massive Parish Prison one block away blighted the square and its immediate neighborhood with a griminess that would last long after the prison itself disappeared.

Thus the dancing in Congo Square did not end precipitously, as some writers have supposed, but gradually, crowded out by the physical growth and the americanization of New Orleans.

The simple passage of time also wrought some important changes. By the 1830s and 1840s, the portion of the slave population born in Africa and old enough to have learned the traditional dances of their motherlands had shrunk significantly. Though they and younger generations continued the dances, their steps and movements increasingly incorporated elements of European dance, a process that had begun much earlier, but which accelerated during the antebellum American decades of New Orleans’ history. In 1843, a local writer noted that many New Orleanians of the time had never seen the pure African dances. He had himself never seen them in the square, he said, but only once in the backyard of a private house, where two women and one man danced while four musicians played and chanted a “vocal chorus.”

Two years later Benjamin M. Norman also commented that the “unsophisticated” old “Congo” dances of the Square’s “primitive days” had ceased. In 1879, a writer for the Daily Picayune, describing New Orleans as it was during his young manhood, noted the new, acculturated African-American dance forms emerging in the 1820s, 1830s, and 1840s, were what he called the “imitations” performed by “the descendants of the original Africans.” He insisted that the African dances, as distinct from the “imitations,” continued in the square only “until about 1819, but not later.” All of which suggests that the 1820s saw the balance between traditional African dances and developing African-American dances tip in favor of the new forms.

The African-American dances in Congo Square continued through the 1830s and 1840s but as they fell under ever-increasing scrutiny and control from municipal authorities, their regularity and frequency diminished. In 1837, the city council authorized “free negroes and slaves to dance in the Circus Square from only 12 o’clock until sunset under surveillance of the police.” In 1845, the council required that slaves at such dances have written permission from their masters and further limited the dances to two-and-a-half hours, between 4 and 6 p.m., during the summer months of May, June, July, and August.

The city also periodically moved to improve the square’s looks. In 1843, the council removed the old wooden railings and turnstiles and surrounded “Place du Cirque with posts connected with iron chains, similar to that of the Washington Square.” In 1845, they planted the square with several rows of sycamore trees set some twenty feet apart. Then in 1850-51, the council had the old wrought-iron fence and gates that surrounded the Place d’Armes taken down and re-erected around Congo Square.

In 1856, the city council adopted an ordinance making it unlawful to beat a drum, blow a horn, or sound a trumpet in the city and proscribing public “immorality” and “indecency.” Next followed another ordinance prohibiting all public balls, dances, and entertainment without permission from the mayor. At the same time, the municipal gardener included another round of tree planting for the square in his city beautification plan. The Congo Square Sunday dancers, intimidated by the presence of the militia, harassed by the police, and hampered by what had become a veritable forest of saplings, came in fewer and fewer numbers after 1856, and before the end of the decade, ceased to come at all. Thus the dancing in Congo Square did not end precipitously, as some writers have supposed, but gradually, crowded out by the physical growth and the Americanization of New Orleans.

So it was that on the eve of the Civil War dancing disappeared from Congo Square. That is to say, the dancing ended as a public institution. But that does not mean that such dancing disappeared altogether. It continued for another thirty years or more, but with ever diminishing frequency, and only in private settings in the city and on isolated plantations. As late as 1880, Lafcadio Hearn saw, in a wood-yard on Dumaine Street, two men beating bones and sticks on drums made from “a dry-goods box and an old pork barrel” while “some old men and women” chanted an African song, and “a few old persons” with tin rattles on their ankles did African dances that, as Hearn pointed out, only the old ones knew how to perform. And, Hearn added, the remnants of such dances, already rare, would soon be “completely forgotten in Louisiana.”

Transformation

A number of factors allowed for the astonishingly long survival of traditional African dances in New Orleans: the high degree of tolerance and accommodation the French in the New World generally accorded subcultures; the city’s isolation during its French colonial history; its Caribbean nexus formed during the thirty-four years Spain governed the colony; its geographical remoteness from the centers of U.S. culture for quite some time after the American purchase; the city’s extraordinarily large African population, which from 1760 until 1840 outnumbered its European population; and, not the least, the inordinate preoccupation of the city’s French Creole host culture with dancing of all kinds, something remarked upon by observers more often even than they remarked upon the African dances themselves.

Alone, however, the unusually long survival of African dances in New Orleans would be of no particular significance. They would represent only an historical curiosity. The real significance of the survival lies in the fact that it lasted long enough for an assimilation process, one peculiar to New Orleans, to take place. Indeed, survival is the wrong word, for it implies an eventual demise. As Ira Berlin and others have pointed out, African culture in the New World did not die, nor was it lost or destroyed. It was transformed. Like the various European cultures transplanted to these shores, the many African cultures joined and blended with each other along with European and the Native American Indian cultures to become a distinct meld of African-American culture.

The African-American meld that came out of Congo Square differed primarily, and importantly, in that it occurred not in the Anglo-Saxon Protestant setting that usually hosted the transformation process, but in a FrenchCreole, Catholic city that had recently become a part of the United States. That fact added what amounted to an extra and subtly complex step in the process. In New Orleans the formative stage of African-American culture involved a blending of African, Indian, and French, plus a few German and Spanish cultural elements. That peculiarly New Orleans black compound then blended with the greater African-American and American cultural meld being formed in the nation at large.

In the case in point, the dance forms that emerged in Congo Square were as uniquely a New Orleans product as jazz was. Those dances almost certainly made their way into the greater American culture via the same route New Orleans jazz did. They are today, in their various derivative forms -popular and serious -as much a part of American, and, indeed, world culture as jazz and its many derivative musical forms and influences are.

—–

Jerah Johnson, PhD., is professor of history and Hub Cotton Fellow at the University of New Orleans, where he has taught since 1959.