Winter 2018

Creole Italian

Nystrom's book explores the backstory of Italian New Orleans

Published: December 3, 2018

Last Updated: March 22, 2023

University of Georgia Press

You toucha dis, you toucha dat,

You toucha everyt’ing—

You pusha dis, you pusha dat,

You never buy notting!

So please no squeeza da banana!

If you squeeza, Officer, please,

Squeeza da coconut!

Prima’s dialect-laden routine in “Please No Squeeza da Banana” deflated and deflected anti-Italian sentiment that bubbled just under the surface of American society during World War II. Despite his self-deprecating and humorous tone, Prima’s genius lay in his refusal to yield ground to xenophobia, choosing instead to showcase rather than diminish his Italianness. This soft approach also proved good for business, a point reinforced by a 1945 Billboard magazine ad for the song that deftly employed the same idiom: “Operators: I think this record will squeeza da nickels into da machinas something terrific! So pleasa no teasa da customers . . . let them hear—please no squeeza da banana.” Like other ethnic minorities, Italians had long since learned to laugh their way to the bank by the middle of the twentieth century.

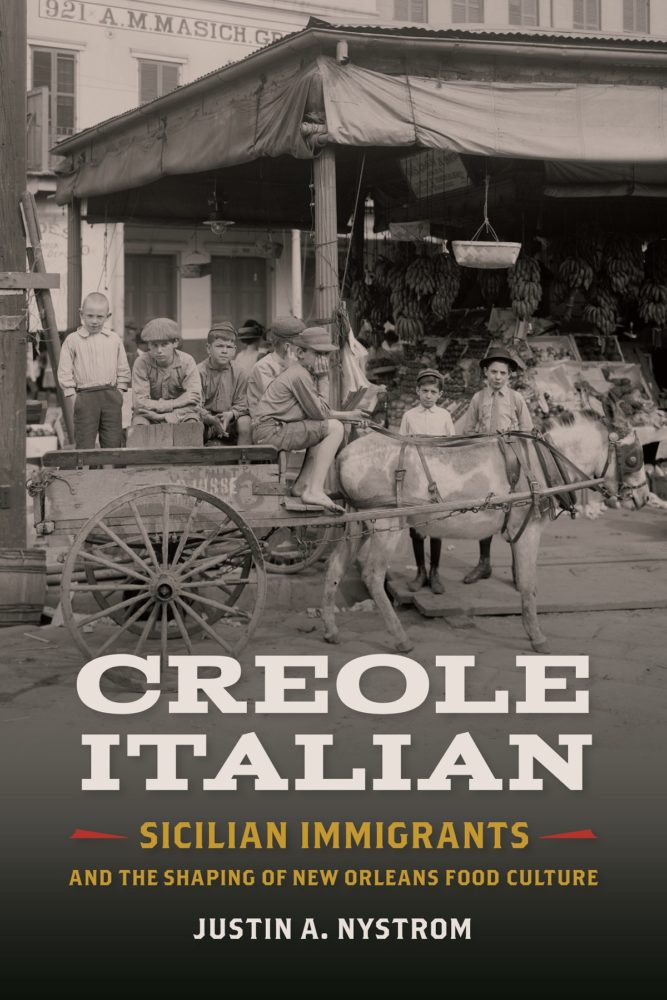

The fact that one might periodically hear a playful tune like “Please No Squeeza da Banana” on an Apple Radio playlist in 2016 or perhaps on a Friday broadcast of WWOZ’s New Orleans Music Show speaks to the endurance of Prima’s connection with Italian-American cultural memory, especially in his native New Orleans. New Orleanians of a rapidly disappearing generation remember well the street peddler of their youth, hawking bananas from a cart, an occupation recalled with hard-earned pride, representative as it was of the immigrant generation’s first toehold on the financial ladder. Indeed, the banana man with his street cries and indomitable hustling occupies an important mythic space in the nation’s immigrant experience, symbolic of the thrift and toil inherent in the struggle to become American. Perhaps it was inevitable, then, that his powerful cultural symbolism would come to obscure the fact that “Tony” was a social construction of remarkably recent vintage, a memory scissored out of time and pasted onto the historical subconscious, one without clear origins and that, on closer examination, raises more questions than answers. How did Sicilian immigrants became so fundamentally associated with the tropical fruit trade when bananas had become a mainstream part of the American diet only during the waning years of the 1890s, after the massive exodus of Sicilians across the Atlantic to North America had already begun? Moreover, bananas are not Sicilian or Italian, so how did these immigrants from the Mediterranean come to market commodities from Central America? Only by tracing the threads of logic to their origin may we uncover the fascinating but largely forgotten chain of human processes that sent millions of Sicilians to our nation’s shores in the decades leading up to the Great War.

We must first acknowledge, however, that what we think we know about the history of Sicilian Americans is only a historical fragment formed during the middle decades of the twentieth century. Indeed, from Louis Prima to the Godfather, popular culture has done much to shape what Americans understand to be true about the history of Italian immigrants generally and Sicilians in particular, a memory paradigm familiar to anyone who comes into more than passing contact with it. Our first mental image finds the immigrant generation packed into the damp hold of an ocean steamer, a desperate lot traversing the Atlantic in search of a new life, however uncertain, that could not help but be superior to the sunny, dusty, backward, and povertystricken one that they left behind. As a class, they were poor, swarthy, Catholic, clannish yet gregarious, industrious, and irrepressibly voluble. In this country, their growing families populated the urban slums of the nation’s teeming cities, where the men and boys crisscrossed neighborhoods peddling bananas and repairing shoes while the matriarch and her daughters sewed piecework in the dimly lit confines of their crowded apartment. Yet by the 1940s, toil, frugality, and the pooled energies of la famiglia had carried this aging first generation and their children to the pleasant bungalows of the nation’s inner suburbs. Here, they gathered after Mass for Sunday supper, an aromatic homage to red gravy followed by a lazy afternoon of cousins playing stickball in the yard and parents and aunts and uncles drinking Chianti while they dealt cards or washed dishes to the melodic tones of Sinatra and Prima drifting from the living room stereo. By the 1950s, the popular imagination saw Italians as the embodiment of the immigrant American Dream even as they preserved a distinct and inherently worthwhile culture, seemingly without effort.

Sicilians in America, however, have a deeper, more complicated past than this powerful twentieth-century construction lets on, a past whose origins lie in a long since vanished transatlantic trade in Mediterranean citrus. The wave of Sicilian peasants that eventually hit American shores at the end of the nineteenth century was proportionally so great that it obscured an earlier migration of the island’s merchant class to the Gulf South and Eastern Seaboard. The steamdriven citrus fleet that these seafaring traders later built supplied the means by which millions of their countrymen fled their homeland. As in New York and Philadelphia, the first significant Sicilian migration to New Orleans began in the 1830s, when Mediterranean lemons began to be sold on the Mississippi River levee. Their debut coincided with a population explosion during which the metropolis grew by more than 120 percent in a decade. Indeed, New Orleans of the 1830s was so awash with German and Irish immigrants that few contemporary observers seem to have noticed these Italianspeaking newcomers save for the marketing of their golden cargoes. Yet like the modest headwaters of the great river that defines the city, the presence of these early Sicilian fruit merchants dictated much about the course of events to come, and the story of Tony, the peddler of bananas, begins with these merchants.

Justin A. Nystrom is an associate professor of history at Loyola University in New Orleans and director for the Center for the Study of New Orleans. He is the author of New Orleans after the Civil War: Race, Politics, and a New Birth of Freedom and the director of the documentary film This Haus of Memories.