Winter 2012

William Joyce: Guardian of Childhood

One of America's best illustrators delights children across the world from his studio in Shreveport

Published: April 15, 2015

Last Updated: October 1, 2018

“To understand pretending is to conquer all barriers of time and space.”

—Ombric, in Nicholas St. North by William Joyce

Located in what was planned to be a biotech research park in Shreveport, Moonbot’s interior was redesigned to reflect the studio’s personality. After threading one’s way through enough security to conjure up thoughts of CIA headquarters, the visitor opens heavy glass doors to enter a slightly futuristic environment gleaming with glass and chrome. A receptionist sits behind a curved desk under a suspended oversized lamp, perhaps ten feet in diameter, apparently activated by a pull chain of wooden balls. (Actually, it turns on by the flick of a switch on the wall.) A lighted case exhibits three Emmys, a Gold Medal from the Society of Illustrators, and other awards Joyce has earned. The Oscar he and his partner Brandon Oldenburg won at the 2012 Academy Awards for The Fantastic Flying Books of Mr. Morris Lessmore has yet to be displayed. The lobby features deep, multihued chairs, some of them mounted like lazy susans that revolve, and above, exposed pipes gleam in foil wrapping. Every surface sports bold primary colors.

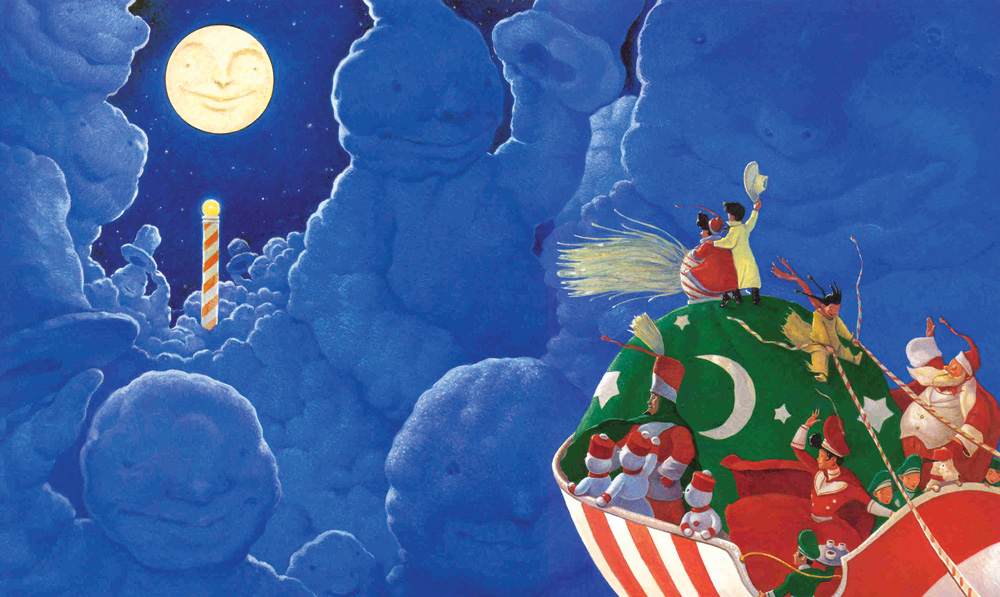

Santa Calls, a children’s book released in 2001, originally published in 1990 but expanded in 2006, William Joyce’s popular children’s book, many of which have been adapted to film.

On either side of the hall leading from the foyer are rooms housing work pods specially designed to give employees space and privacy without putting coworkers beyond reach of one another. Books are stacked high on desks and tables, while framed illustrations from The Leaf Men, Dinosaur Bob, and other books and films by Joyce hang on the walls or lie propped against them on the floor. Office whiteboards are crowded with lists of projects, deadlines, and assignments. Storyboards charting Moonbot’s projects in progress cover the walls of two large rooms. The main corridor ends at a screening room where staff can examine the craft of moviemaking (the film library includes Buster Keaton titles and Singin’ in the Rain, among others) or review their own projects. Oversized red beanbags that spill across the floor seem to be the seats of choice. The Bots, as the studio’s young, energetic, and talented employees are called, work in a space that combines innovative technology with the best of artistic imagination.

At the heart of all this enterprise is William Joyce, a bespectacled artist of 55 years whose seriousness about visual storytelling is betrayed on occasion by a sense of mischief. For his attendance at the Academy Awards, for example, he and Oldenburg wore tuxedos made by Dickies Work Apparel. Joyce added a black fedora to his ensemble. On any ordinary day, however, he can typically be seen in white jeans and a tieless shirt with the sleeves rolled up, his beard and mustache neatly trimmed, and his graying hair cropped short. On occasion Joyce wears a scientist’s white lab coat with a small blue Moonbot logo, which resembles one of his animated robot characters. He is neither short nor tall, neither attention catching nor invisible. Where the ambience of Moonbot Studios is inventive, ingenious, and original, fairly shouting its creative qualities, Joyce himself gives few external clues as to what must be going on inside.

Natural talent

Those inner impulses to create art came naturally. Joyce knew early on that he was meant to draw. As a pre-schooler in the late 1950s Joyce was struck by the illustrations he found in Maurice Sendak’s Where the Wild Things Are, and in the fourth grade, at A.C. Steere Elementary School in Shreveport, he produced his first book. By the time he reached Byrd High School, he was drawing cartoons for High Life, the student newspaper. When his post-high school art instructors urged him to change his style, he decided to study film, graduating with a BFA from Southern Methodist University in Dallas, Texas. That experience turned out to be good training for a visual storyteller.

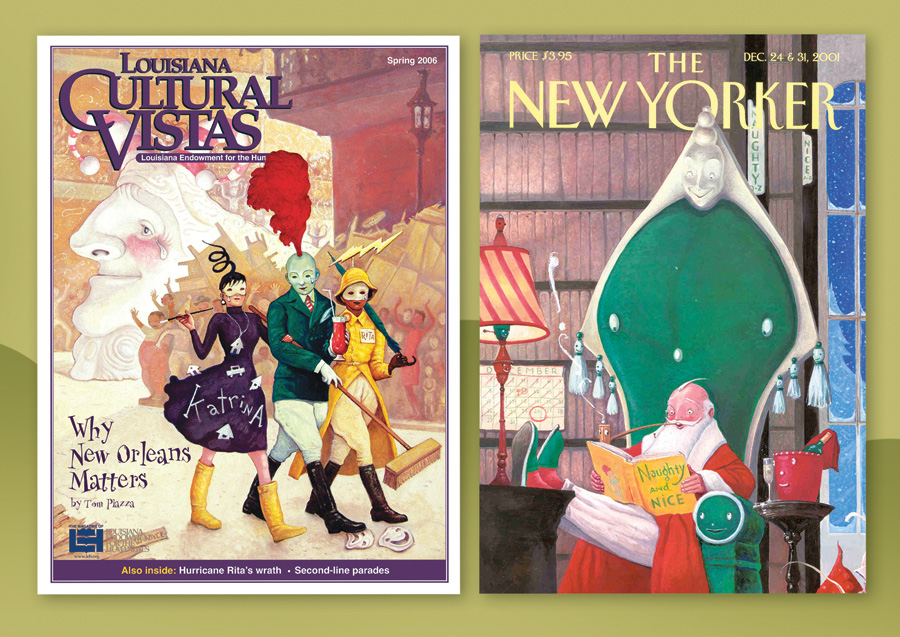

William Joyce graciously gave Louisiana Cultural Vistas permission to print an illustration originally intended for the Feb. 27, 2006, edition of The New Yorker . Joyce was commissioned by The New Yorker to create a painting related to the first post-Katrina Mardi Gras in New Orleans, but the breaking news of Vice President Dick Cheney’s accidental shooting of a friend on a hunting trip supplanted this original cover idea.

After college Joyce spent some time in New York, but when an art dealer viewing his portfolio remarked that Joyce could do what he did anywhere, he returned to Shreveport, and stayed. He liked being around people he knew. Although success was not immediate, his creative impulses just kept coming. “If you really love to write,” he says, “and you really love to draw, you just have to keep doing it no matter what anybody says.”

He did “keep doing it,” and by the mid-1980s the reading public began to take notice of the whimsical tales and lush illustrations found in books such as George Shrinks and Dinosaur Bob and His Adventures with the Family Lazardo. The 1990s saw even more productivity, including A Day with Wilbur Robinson, based, according to Joyce, on his own family; Santa Calls (set partly in Abilene, Texas, which prompted the city to establish its National Center for Children’s Illustrated Literature); and Rolie Polie Olie (introducing a robotic character destined in the next decade to star in Snowie Rolie, Sleepy Time Olie, and Big Time Olie).

Several of Joyce’s vibrant characters leapt from the pages and into the realms of television and film. George Shrinks aired daily as a PBS cartoon, Rolie Polie Olie turned into a television series distributed by Disney, and A Day with Wilbur Robinson became the animated feature film Meet the Robinsons, released by Walt Disney Pictures in 2007. The beauty of the illustrations, done mostly in oil or acrylic, coupled with narratives tinged with mythic themes and characters and tempered by humor, appealed not only to children, but to adults as well.

Joyce’s proven work in animation prompted an invitation from John Lasseter to work on Disney/Pixar’s Toy Story, the first feature film to be made entirely with computer generated imagery, released by Walt Disney Pictures in 1995. Joyce went on to create conceptual characters for A Bug’s Life (1998) and art design for many other films by DreamWorks, Twentieth Century Fox, and Disney, including Meet the Robinsons (2007) and Mr. Magorium’s Wonder Emporium (2007), about a toy store owned by an eccentric 243-year-old. During these same busy years, Joyce was commissioned to decorate the Christmas windows of Saks Fifth Avenue’s flagship store in New York, and he created covers for The New Yorker.

Creative partners

Enter Brandon Oldenburg, a Texan who, after graduating from the prestigious Ringling College of Art and Design in Sarasota, Florida, co-founded Reel FX Creative Design Studios in Dallas. Just as William Joyce grew up drawing, Oldenburg grew up making movies. A longtime fan, in 1998 Oldenburg approached Joyce about a possible collaboration. The partnership has never ended. As Oldenburg puts it, “We get each other on so many levels.”

A still from the award-winning film, The Fantastic Flying Books of Mr. Morris Lessmore, depicts the title character encountering a library full of living books.

A few years later Lampton Enochs left Katrina-ravaged New Orleans with his business partner, Alissa Kantrow, to co-found what became Louisiana Production Consultants, a business designed to bring movie and television projects to North Louisiana. After meeting Joyce and his wife Elizabeth, the four became friends and had the idea of establishing a studio in Shreveport. With Enochs to cover the financial and contractual aspects of the venture, and Joyce working his magic, adding Oldenburg to the team was the next logical step. Despite his ongoing collaboration with Joyce, Oldenburg, living happily in Dallas with his wife and two young children, was not eager to move. An additional impediment was that he had been hired as creative director for the upcoming London tour of Michael Jackson, his longtime favorite musician. Jackson’s sudden death in June 2009 changed Oldenburg’s future. He put his Dallas home on the market the next weekend and prepared to move 190 miles east to Shreveport. In August 2009 Enochs, Oldenburg, and Joyce founded the animation and visual effects studios called Moonbot. Trish Farnsworth-Smith, who had first worked with Joyce on projects with the Shreveport Regional Arts Council, came on board to help with managing howdy ink, a precursor of Moonbot, and then became head of production at Moonbot Studios.

The new collaborations required new work space. Joyce’s existing studio at Centenary College, where he serves as an artist-in-residence, could not adequately house the rapidly growing Moonbot Studios. Even after acquiring larger quarters, however, Joyce opted to maintain offices at the college, where he conducts workshops from time to time. He also accepts interns from Centenary who get firsthand experience working with animation and film.

Joyce and Oldenburg won Oscars for Best Animated Short Film at the 84th Annual Academy Awards in February 2012.

The staff grew as well, bulking up from two and a half people, to more than 40 Bots now inhabiting the studio, many of them graduates of the Ringling School of Design or from the School of Design and Production at the North Carolina School of the Arts. The technology people often come from Texas A&M. Mostly from the South, the bright and creative team is close, often socializing at pool parties or watching movies together at the studio.

Inspiration from life experiences

Where do the story ideas come from? Joyce claims much of his work is autobiographical. The Rolie Polies caricature members of his own family, which he calls “a congenial horde of southern screwballs.” Almost everything in A Day with Wilbur Robinson has some basis in truth, he says, even the singing frogs. As a boy Joyce raised frogs from tadpoles, and their trilling sounds filled the summer air. Since his family enjoyed listening to Louis Armstrong records, Joyce combined the two experiences in Wilbur Robinson by creating animated frogs that sing like Louis Armstrong. Sometimes the genesis of a story element is less literal. He claims that writing is his way of dealing with both the good and the painful things in his life. In elementary school, for example, he coped with math anxiety by making stories and drawings in which “the vengeful number 5s” did battle with a child who had a giant eraser cannon that would eradicate them.

The truth is that Joyce’s ideas can come from anything — an old movie, a song, a random observation. George Shrinks, is based on King Kong — in reverse. Where King Kong was too big for everything, George spends his time in a world in which he is too small. Whatever their source, the stories are marked by an absence of adult cynicism and the presence of a boisterous imagination. Michael Patrick Hearn quotes Joyce as saying: “I try to make television that actually stimulates that animation gland and drives [young viewers] almost into an imaginative conniption fit. I want them so jazzed after watching one of my shows that they can hardly stand it, that they have to go out and tell somebody or do something or reenact what they have seen by using imaginative play.”

Part of the attraction of William Joyce’s works is that beneath the fantasy and whimsy lie important themes. Repeatedly the reader/viewer is confronted with the importance of responsibility, love, friendship, kindness, and curiosity. The characters demonstrate the value of believing in possibilities, experiencing the power of daydreams and practicing basic, everyday goodness. A comment made in E. Aster Bunnymund and the Warrior Eggs at the Earth’s Core! makes it clear that at the top of the pyramid of good things is the imagination. Speaking of a magical book written by Katherine, one of the major characters in E. Aster Bunnymund, the narrator says: “The ink and paper she used were ordinary, but her mind, her imagination, was what gave the words and pictures their great power: the power to connect her to anyone who read her stories.” The observation seems to identify the source of the extraordinary pull of Joyce’s own works as well.

William Joyce at work on Santa Calls in his home studio, 1993.

The imagination is working overtime at Moonbot Studios these days, producing an abundance of projects. Chief among them is the “Guardians of Childhood” series, which will appear in picture book, chapter book, and film form. (Rise of the Guardians, the film based on the book series that was released on Nov. 21, has already received the Hollywood Animation Award at this year’s 16th-annual Hollywood Film Festival and Awards.) The 12 books will be published by Simon and Schuster, and Joyce is executive producer for the animated feature film based on his series at DreamWorks Animation. All of the projects will tell, in their own way, the back-stories of some of childhood’s favorite characters, such as the Easter Bunny. That is, they will focus on who the famous characters were and what they did before they became icons. For example, readers will be startled to find that Saint Nick was once a headstrong young warrior who used his skill with weaponry to plunder treasuries around the world. Toothiana, Queen of the Tooth Fairy Armies and The Sandman: The Story of Sanderson Mansnoozie, both released in October of 2012, reveal the surprising histories of the Tooth Fairy and the Sandman. The tales have heroes and villains, and the forces of good and evil do battle, creating a powerful mythic quality. They reflect Joyce’s comment made in a speech to the annual meeting of the American Library Association. “Kids,” he said, “need to believe in wonder and heroes and good things.”

Other current projects at Moonbot include writing, producing and designing an adaptation of the picture book The Leaf Men and the Brave Good Bugs as a computer animated feature film to be released by Blue Sky Studios in 2013 under the title Leaf Men. Work is also underway on The Numberlys, a short film and a book that will retell the 1927 silent classic Metropolis for children. The Numberlys are beings who, lacking an alphabet, use numbers instead of letters. In an app for interactive viewing that is already available, the viewer can break the numbers apart to make new shapes in a series of games. From a field of more than 1,700 nominees, Moonbot’s iPhone/iPod app has been named as one of the finalists for the Innovation by Design Award by Fast Company magazine, which recognizes the best design-driven innovations of the year.

Winning an Academy Award

William Joyce and Moonbot Studios received increased public attention when The Fantastic Flying Books of Mr. Morris Lessmore, Moonbot’s first project, won the Academy Award for the best animated short film in February 2012. It also won six major film awards in addition to the Oscar. Surprisingly, the story started out as an idea for a book, but as the working relationship with Oldenburg prospered and Moonbot Studios came into being, it turned into a film, with Lampton Enochs as a co-producer.

Morris Lessmore is notable for its use of miniatures, computer animation, 2D animation, matte paintings, and even practical shots of dust and debris, but it became truly cutting edge when Ken and Keith Hanson of Twin Engine Labs headed up a team that created an app for the short film that made “interactive storytelling” possible. (Apple brought out the iPad when the film was in the middle of production.) By way of the app, the reader/viewer actually becomes part of Morris Lessmore’s world through games and hidden content. There’s even an opportunity to play a piano featured in the movie, inviting children to puzzle out the secrets and to be curious. Not surprisingly, in the first week after its release, the Morris Lessmore app moved to the top of Apple’s iPad app chart in the U.S., and at different times it has been the top book app in 21 countries. In addition to highly positive reviews and many awards, it also won App of the Year for 2011 from Apps Magazine and Best iPad at ipadinsight.com. Morris Lessmore stands as an example of the wide range of creativity of William Joyce and his colleagues to tell stories in new ways and new media. What began as an idea for a book, became an animated short film that generated an app. The printed book was released in June 2012 and by the following August had risen to first place on the New York Times Children’s Best Sellers list.

Despite the extensive use of technology to produce Morris Lessmore, the film actually celebrates the joys of reading. It tells the story of a book lover who cares for a living library, then writes a book that recounts “his joys and sorrows, of all that he knew and everything that he hoped,” according to the Moonbot Studios Web site. As the lush visual images roll by, the soundtrack plays “Pop Goes the Weasel,” sometimes joyously, sometimes mournfully. Morris Lessmore reflects Joyce’s response to seeing how stories gave solace to children displaced by Hurricane Katrina, an experience that reinforced his belief in the power of books to heal troubled souls. Although the children were crowded in shelters, their imagination took them to a better place.

The magic of Morris Lessmore, and of William Joyce’s works in general, lies not only in the stories themselves, but in the visual narratives as well. Studying great illustrators such as Maxfield Parrish, Beatrix Potter and N.C. Wyeth, Joyce developed a sophisticated technique that uses a variety of media including watercolor, oil, acrylic, pen and ink, colored pencils and computer graphics. The result is hauntingly beautiful illustrations that surprise and delight. The more one looks at them, the more one sees: faces and hats and animals appear in what initially may look to be only a cloud. While his illustrations are highly collectable, they are not for sale these days. Although he sold some early in his career, today Joyce keeps the originals, many of which hang on the walls of Moonbot Studios.

William Joyce’s honors have been almost as numerous as the books, films, and apps. As the new century began, Newsweek named him one of the top 100 people to watch in the new millennium. Then came the three Emmys for the Rolie Polie Olie series that aired on the Disney Channel, and in 2008 Joyce received the Louisiana Writer of the Year Award for his contribution to the “literary intellectual heritage of Louisiana.” But it is not the awards that keep William Joyce writing and drawing. Instead, he seems driven by his own imagination to create books, films, television and art that speak to the imagination of others. In many ways he is like Katherine in E. Aster Bunnymund: “She would sometimes write stories that were different from what had happened but were about how she felt or what she wished had been … she needed to do it.” William Joyce needs to do it as well.

Ann B. Dobie, Ph.D., is professor emerita of English at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette, where she directed the graduate program in rhetoric and the university’s writing across the curriculum program. Her books include Fifty-Eight Days in the Cajundome Shelter, a fourth edition of Theory into Practice: An Introduction to Literary Criticism, and Civil Changes: Civil Service in Louisiana. She currently serves as state coordinator for the Louisiana Writing Project and as a consultant for the National Writing Project.

Neil Johnson is an independent photographer who works from his studio in Shreveport: www.njphoto.com. He was honored with the Michael P. Smith Documentary Photographer Award by the Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities in 2011.