Fall 2024

A Different Kind of Buffalo

One person’s trash fish is another’s delicacy

Published: September 1, 2024

Last Updated: December 1, 2024

Sam Stukel, US Fish and Wildlife Service

The smallmouth buffalofish.

The lyric “Oh give me a home where the buffalo roam” usually calls to mind the massive shaggy four-footed bisons of the American plains. But for some residents in a swath of this country ranging from Montana, Minnesota, and Wisconsin all the way down to Texas, Arkansas, and Louisiana, “buffalo” evokes an entirely different species. Here, the word calls forth images of piscatorial denizens of the Hudson Bay and Mississippi River waterways: buffalofish. Ictiobus cyprinellus (bigmouth buffalo), Ictiobus bubalus (smallmouth buffalo), and Ictiobus niger (black buffalo) are long-lived fish that are helpful to the ecosystem, and all three are found in Louisiana waters.

Buffalofish have a storied history, valued as a catch for centuries. They were caught and eaten by Lewis and Clark on their 1804 expedition; in July of that year, Lewis noted in his journal the variety of fish they’d observed and caught, which included “cat, sunfish, &c &c perch Carp or buffaloe fish.” The juxtaposition with the word carp is interesting, indicating that Lewis, like many still today, may have struggled to differentiate the native buffalofish with the non-native (and often invasive) carp. Compared to carp, buffalofish have a rounder and deeper body and mouths positioned more toward the bottom of their head, as they feed on silty riverbeds.

Nowadays, though, many folks dismiss the buffalo, considering the bony fish not worth eating. Others, many of them African Americans, delight in the fish, deep frying the fish’s thick ribs and eating them with relish.

As a native New Yorker, I’d never heard of buffalofish, much less fried buffalo ribs. I first learned about them while shopping in Washington, DC, with a friend who was a transplanted Shreveport native. One day, while strolling with him through a fish market in the nation’s capital, admiring the seasonal bounty—blue crabs in abundance, silvery butterfish, and other delights—he spied some buffalofish and went into raptures. I’d never heard of the fish; it looked a bit like a carp to me. The loud praises sung by my friend enticed me to learn more about it.

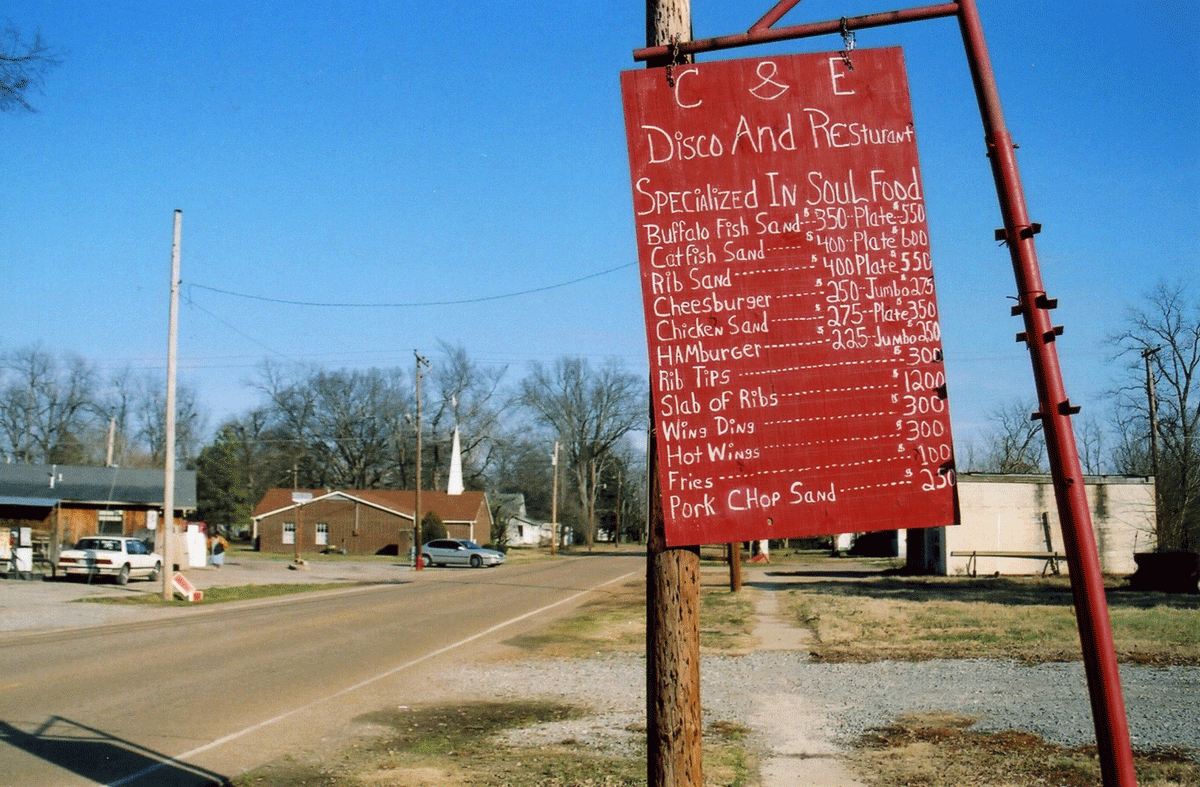

A menu at a southern soul food restaurant advertising buffalofish sandwiches. LRD615 on Flickr, Wikimedia Commons under C.C. 2.0 license

Pound for pound, buffalo were the predominant focus of the freshwater commercial fishing industry from 1920 through 1940; in 1936 more than ten million pounds of buffalo were caught. The buffalofish that seems to be most relished in the South is the bigmouth buffalo, which have been known to live up to 127 years and can weigh as much as seventy pounds. They are slow-moving bottom feeders, using their heads and mouths to stir up murky bottoms and uncover food like small crustaceans and insects that might be buried there. A popular game fish, they are fighters that resist being line-caught. In the northern parts of the country, unregulated bow fishing is wreaking havoc on some of the bigmouth buffalo populations. But the fish continues to thrive in the South.

While all Louisiana fisherfolk know how to prepare and savor buffalo, the species that is noted for being a bony fish and a bottom feeder was a hard sell. In the mid-twentieth century, smallmouth buffalo, marketed as white buffalo, were enjoyed mainly by the Jewish community, while bigmouth buffalo and black buffalo were sold as number 2 grade buffalo and were consumed primarily by African Americans. A market study by the Southern Regional Aquaculture Center in the early 2000s revealed that 83 percent of the catch went to African Americans while 6 percent went to Asians. The major markets for the fish were in urban areas in northern and western states, areas where the Great Migration and subsequent migrations created populations longing for the foods that evoked their southern origins. Buffalo is a fish with a strong link to the past, to memories of fishing in lakes and reservoirs and to gatherings at local fish fries, where the catch is cut horizontally into distinctive ribs, each with a meaty bit of fish attached. The pieces are dredged in a seasoned mix of flour and perhaps a bit of cornmeal and then deep fried to crisp golden brown, often served with hush puppies and cole slaw. Eaten with a dash or two of hot sauce, one person’s trash fish becomes another’s delicacy. No less a culinary omnivore than Andrew Zimmern highlighted buffalofish on the Greenville, Mississippi, episode of his show Bizarre Foods, calling it “the best tasting fish that no one eats.” If he’d come a bit further down the Mississippi, he might have learned that here in Louisiana there are plenty of folks who not only eat buffalo but savor it.

Several years after the stroll through the DC fish market with my friend, I finally had the pleasure of gnawing on some delicious crisply fried-fish ribs at a backyard fish fry in New Orleans. I savor the knowledge that in Louisiana, I do have a home where the buffalo roam.

Jessica B. Harris is the author, editor, or translator of eighteen books, including twelve cookbooks documenting the foodways of the African Diaspora. In March 2020, she became a James Beard Lifetime Achievement awardee.