Ada Thomas

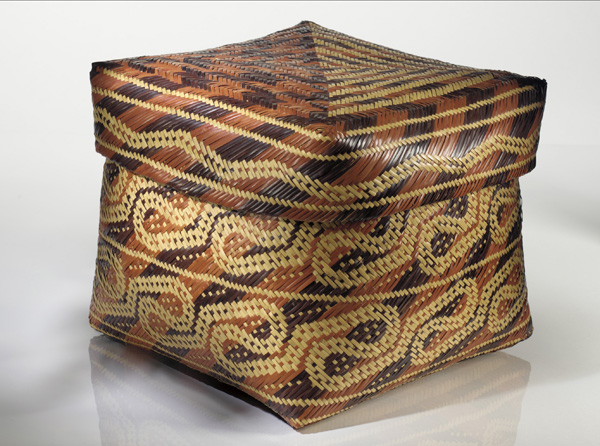

Ada Thomas was one of few remaining weavers of traditional Chitimacha split-cane, double-weave baskets.

Courtesy of the National Museum of the American Indian.

A color photograph of a Native American basket with cover.

Ada Thomas was one of few remaining weavers of traditional Chitimacha split-cane, double-weave baskets. These baskets consist of cane strips dyed red, black, or yellow and woven into intricate designs. Dating back hundreds of years, the distinctive patterns have become a hallmark of Chitimacha identity. Ada, who learned to weave from her grandmother, won a $5,000 Craftsman’s Fellowship after meeting a representative of the U.S. Department of Interior’s Arts and Crafts Board. With the award, she developed an extensive collection of baskets, now part of the Department of the Interior’s permanent Ada Thomas collection. In 1983, the National Endowment for the Arts honored her contribution to the traditional arts with a National Heritage Fellowship.

Ada Vilcan was born July 31, 1924, on the Chitimacha Reservation, one mile west of Charenton, in St. Mary’s Parish. She was the fourth child of Henry Vilcan and Jane Bernard. Prior to European settlement of the United States, the Chitimacha Indian tribe consisted of seventeen bands of hunters and fishermen scattered across Louisiana. By the turn of the twentieth century, the government had reduced Chitimacha land to about 265 acres located in the area near Charenton.

Thomas attended elementary school in a one-room schoolhouse on the Chitimacha Reservation, where grades one through eight were taught together. When she was about twelve years of age, she learned traditional basket-weaving techniques from her grandmother, Christine Paul, who was a teacher at the school. When her grandmother retired, her aunt, Pauline Paul, took over teaching at the school, and Thomas continued her studies of basket weaving from her. This Chitimacha basketry tradition dates back to at least the early 1700s, when it was first noted by European writers.

In the late 1930s, after Thomas earned her eighth-grade certificate, she wanted to continue her schooling, but there was no high school on the reservation and she wasn’t allowed to attend either the white or the black high schools in her area. So she moved to New Orleans to go to high school, and while there she went to a museum and was surprised to see some Chitimacha baskets on display. “For the first time, I felt proud of who I was,” she said.

Upon graduating from high school, she moved away from Louisiana. “I traveled,” she recalled, “and worked all over the United States and finally settled in Miami, Florida, where I got married and stayed for the next twenty-one years. When my husband got sick, we returned to the reservation.” In the mid-1970s, Thomas decided to resume making traditional baskets, after nearly thirty years away from the craft.

For Thomas, the process of creating Chitimacha baskets was long and tedious. To begin, she gathered swamp cane or cane reed from the bayous near where she lived. In doing so, she selected reeds of different ages for each color she needed. She then split and peeled the reeds by hand before curing and drying them. Traditionally, the reeds were soaked in dew and sun for eight days to bleach them. Most were then dyed by soaking for seven more days in colored water. The dyes were all natural. “A root of a wild plant,” Thomas explained, “is used for red coloring. The outer bark of the regular walnut (tree) is used for the black coloring, and lime is used for the yellow coloring.”

To make the double-woven basket, Thomas worked simultaneously with numerous strands of red, dark brown, and other naturally colored cane. She interlaced the cane in one continuous weave, creating the inside basket first. When it was completed, she doubled back, weaving the outside basket, carefully selecting strands of cane at each point throughout the weaving process to construct a design. As she neared completion of a basket, the design became readily apparent. Traditional designs included Alligator Entrails, Bull’s Eye, Rabbit Teeth, Snake Design, Bear’s Earrings, Fish, and Muscadine Peel. Most of these designs reflected the tribe’s close association with nature and aspects of its life in the Louisiana bayous.

Throughout the last years of her life, Thomas worked to revive interest in Chitimacha basketry traditions. “I would like to see our Indian people start over and learn basket weaving. The interest is there, but finding and processing the materials is hard to do. To me, it would be an interesting pastime or hobby, but none of the young girls weave baskets to keep the Chitimacha tradition alive.”

Ada Thomas died on September 6, 1992, in Charenton.