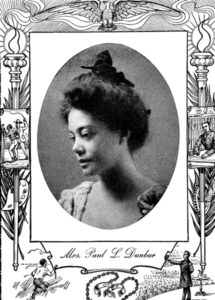

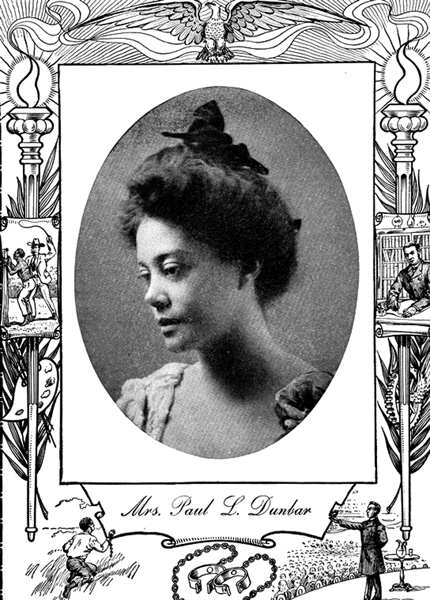

Alice Dunbar-Nelson

New Orleans native Alice Dunbar-Nelson was one of the founders of the Harlem Renaissance literary movement.

Courtesy of the New York Public Library.

Black-and-white reproduction of a photograph of Louisiana writer Alice Dunbar-Nelson with a decorative border.

New Orleans native Alice Dunbar-Nelson, the daughter of a former enslaved person, was an important literary figure in the Harlem Renaissance, an outpouring of African American creativity in 1920s and 1930s. One of a few published African-American women writers working in multiple genres, Dunbar-Nelson rose from humble beginnings to become a successful teacher, journalist, and fiction writer. Though she spent much of her later life outside Louisiana, she consistently championed the rights of women and African Americans across the United States, advocating anti-lynching campaigns, women’s suffrage, and social equality throughout her work.

Life and Career

Born Alice Ruth Moore on July 19, 1875, in New Orleans, she was the child of Patricia Wright and Joseph Moore. Dunbar-Nelson’s mother had been enslaved in Louisiana and Texas, not obtaining her freedom until 1865, two years after the Emancipation Proclamation. Once free, Patricia Wright returned to New Orleans where she made her living as a seamstress. Less is known about Dunbar-Nelson’s father. Some have suggested that he was a white man who left the family early in Dunbar-Nelson’s childhood, while others maintain he was a merchant marine.

Despite the economic and familial hardships of her youth, Dunbar-Nelson excelled in her studies and graduated from high school at the age of fourteen. She went on to earn her teaching certificate from Straight College (now Dillard University) one of the first historically black colleges in the United States. After graduation, she worked a teacher in the New Orleans public school system. In 1895, Violets and Other Tales, her first collection of short stories was published in The Monthly Review. Moving to New York to pursue her literary interests, Dunbar-Nelson continued her education by taking courses at Columbia University and the University of Pennsylvania. She earned a master’s degree from Cornell University, where she wrote her thesis—a section of which was later published in Modern Language Notes—on William Wordsworth.

Dunbar-Nelson had a tumultuous personal life. In 1898, she married African-American poet Paul Laurence Dunbar, who reportedly fell in love with her after reading her first collection of stories. Amidst suspicions of domestic violence, Dunbar-Nelson ended the marriage only four years later. During that period, she published her second collection of short stories, The Goodness of St. Rocque and Other Stories (1899). Like her earlier collection, it included stories, sketches, and poetry describing streets and neighborhoods in New Orleans, as well as imaginative tales of the people who populated the multiracial city.

Dunbar-Nelson’s early writings focused primarily on Louisiana Creole history and culture, paying particular attention to class and gender divisions. In her short stories and sketches, she draws intimate pictures of New Orleanian life. Evoking images of street scenes and individual lives of working people, Dunbar-Nelson’s descriptions vividly portray the small triumphs, petty grievances, and real hardships people experienced living in the bustling city.

After separating from Paul Dunbar, Alice Dunbar-Nelson moved to Wilmington, Delaware, where she took a job teaching at Howard High School. From 1910 to 1911, she was secretly married to Henry Arthur Callis, a fellow high school teacher. The marriage may have been kept secret because he was younger than she, and because it was thought to be against school policy for teachers to be involved with each other. When that marriage ended, she maintained a long-standing intimate relationship with Edwina Kruse, the principal and founder of Howard High School. She married her third and last husband, Robert Nelson, in 1916.

While in Delaware, Dunbar-Nelson launched a newspaper, the Wilmington Advocate (1920–1922), dedicated to the promotion of racial uplift. Between 1926 and 1930 she was a columnist, writing short pieces for From a Woman’s Point of View, later called Une Femme Dit [A Woman Speaks], for the Pittsburgh Courier, and As in a Looking Glass for the Washington, DC, Eagle. She also participated in organizations promoting women’s issues and racial equality, serving on the Women’s Committee on the Council of Defense. In the last decade of her life, she served as Executive Secretary for the American Friends Interracial Peace Committee.

Literary Achievements

Dunbar-Nelson was among the major writers of the Harlem Renaissance, which also included W. E. B. DuBois, Zora Neale Hurston, Langston Hughes, Nella Larson, George Schuyler, and Alain Locke. Like many writers of color in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, she had to negotiate the expectations of a middle-class, white readership, who hungered for fiction heavily laden with dialect and local color that confirmed their racialist attitudes. As a mixed-race female writer and activist, Dunbar-Nelson struggled not only against racism, she fought sexism from her literary and professional peers, many of whom were involved in the struggle for racial equality.

Beginning in the 1980s, a rediscovery and reissue of Alice Dunbar-Nelson’s work spurred a surge in critical attention. Some scholars have linked her fall from favor during the middle to late twentieth century to her ambivalence about racial binarism. Despite her public support for racial solidarity among African Americans, Dunbar-Nelson rejected the idea of a singular African-American identity or politics that focused primarily on masculine achievements. Instead, she was hesitant to subordinate class, gender, and ethnic disparities to racial differences. Other scholars have faulted Dunbar-Nelson for not taking a more critical view of racism and sexism in the South. When considered within its historical context, however, Dunbar-Nelson’s treatment of women, minorities, and the poor helped illuminate a world rarely seen in other literature. She died from heart disease on September 18, 1935.