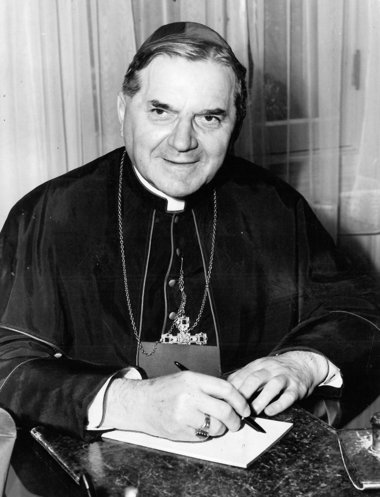

Archbishop Joseph Rummel

Archbishop Joseph Rummel was among the first religious leaders in Louisiana to proclaim the immorality of racism and ordered the desegregation of Catholic schools in New Orleans.

Courtesy of The Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities

Archbishop Joseph Rummel. The Times Picayune

Joseph Rummel, ninth archbishop of New Orleans, is remembered as the leading proponent of civil rights among Louisiana’s Catholic community in the 1950s and ‘60s. Following the US Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka decision in 1954, Rummel called for the desegregation of parish activities in southeastern Louisiana and ordered the cessation of religious services to an entire church congregation for prohibiting an African American priest from performing Mass. Rummel proclaimed the immorality of racism, ordered the desegregation of archdiocesan schools, and excommunicated three people for opposing the church’s integration attempts.

Early Life and Education

Joseph Francis Rummel was born in Baden, Germany, on October 14, 1876. He immigrated to New York City with his parents at the age of six. He attended St. Boniface Elementary School in the city; St. Mary’s College, a high school, in Pennsylvania; and St. Anselm College in New Hampshire. Rummel later enrolled at St. Joseph’s Seminary in Yonkers, New York, and furthered his studies at the North American College in Rome. In 1902 he was ordained as a priest, and for roughly twenty-five years, Rummel performed parish duties in New York and led relief work for immigrant German children.

Episcopal Administrations

In 1928 Pope Pius XI named Rummel as bishop of Omaha, Nebraska. Following the death of Archbishop John William Shaw, Rummel was installed as the ninth archbishop of New Orleans on March 9, 1935. He served for thirty years (1935–1965), the longest archdiocesan administration in New Orleans history. In 1938, Rummel held the first National Eucharistic Congress in the South, with the theme “Christ the Way, the Truth, the Life.” More than two thousand priests, religious, and laypersons helped to plan the event, which had more than one hundred thousand people at its final ceremonies. In 1944 Rummel launched the Youth Progress Program to raise funds for the expansion of archdiocesan youth programs and schools. From 1944 to 1945, the campaign raised more than $2 million to expand and build new schools. Between 1940 and 1960, more than $10 million was spent on archdiocesan construction, including one hundred schools.

Fight for Desegregation

In 1948, in the midst of strict Jim Crow segregation across the South, Rummel integrated Notre Dame Seminary in New Orleans. Three years later, the archbishop ordered that “white” and “colored” signs be removed from all parish facilities, but this action had little influence, due in large part to the racial preference of church ushers to continue pew segregation. In 1951 Rummel integrated St. Joseph’s Seminary in Covington, and founded St. Augustine High School, the for African American males in New Orleans..

St. Joseph Seminary (founded in 1891) and Notre Dame Seminary (founded in 1923) had been established for white novices, while the Josephite House of Studies in New Orleans had been established in 1909 for African American novices. These establishments were in accord with the 1884 Third Plenary Council of Baltimore’s suggestion of establishing separate facilities for black and white Catholics, to protect the church from internal race dissension. With the integration of St. Joseph’s Seminary, a haven was provided for anti-segregationist social groups, such as the Commission on Human Rights and the Southeastern Regional Interracial Commission. By integrating Notre Dame Seminary and St. Joseph’s Seminary, Rummel became the first southern Catholic bishop to accept African Americans into major and minor seminaries.

Although Rummel had integrated southern Louisiana seminaries and moved to create an African American high school, he was silent on issues related to the desegregation of Catholic higher education. Several progressive priests, including Father Joseph Fichter of Loyola University in New Orleans, called for the integration of southern Catholic universities. Noting that such secular universities as Tulane and Louisiana State University had already integrated, Fichter contended that Catholic educators—not their secular peers—should have led such moral action. Despite Fichter’s attempts to persuade the archbishop, Rummel left the desegregation of Catholic universities up to their administrations. Loyola University and Xavier University, Louisiana’s Catholic institutions of higher education, enforced racial segregation until the 1950s.

In 1953, however, Rummel called for the desegregation of Catholic schools in New Orleans. The archbishop experienced backlash from several prominent white laypersons. In response, Rummel issued the pastoral letter, “Blessed Are the Peacemakers,” in which he denounced the cruelty of racism. Despite this public letter, Rummel continued to face opposition to desegregation. After the Brown decision of 1954 that struck down the “separate but equal” rule established in the Plessy v. Ferguson case of 1896, Rummel redoubled his efforts to end Church discrimination.

Despite Rummel’s denouncement of racial prejudice, white parishioners in the community of Jesuit Bend barred the Rev. Gerald Lewis, an African American priest, from celebrating Mass at St. Cecilia’s Chapel in 1955. As a result, the archbishop issued an interdiction that halted Masses and the dissemination of Holy Communion to the community for three years. Following the Jesuit Bend interdiction, Rummel declared racial segregation to be morally wrong in the pastoral letter, “The Morality of Racial Segregation.” In 1956 local members of the Ku Klux Klan burned a cross outside the archbishop’s residence. Undeterred by the Klan’s actions, Rummel announced in his letter “Integration in Catholic Schools” his plan to desegregate all archdiocesan schools.

In 1958 Rummel began a campaign to fund the construction of four new Catholic high schools in Jefferson Parish; one of them became known as Archbishop Rummel High School. Despite the opening of these schools, Catholic educational integration continued to face opposition. Several parents removed their children from Catholic schools in favor of “white-only” institutions. In response to growing concerns that the loss of so many white students would threaten the viability of parish education, Rummel wrote a letter titled “Reopening of School” in 1960 to remind parents and teachers of their responsibilities to the church and that parish schools would open despite possible low enrollments.

Final Years

By 1960 Rummel’s health began to decline, and Bishop John Patrick Cody was appointed coadjutor to Rummel in August 1961. With Cody’s aid, Rummel ordered the formal integration of all Catholic schools in 1962. In response to this order, three persons came forward as prominent protesters: Leander Perez, Jackson Ricau, and Una Gaillot. Rummel excommunicated all three for their opposition to Catholic school integration. After years of battling parish segregation, Rummel retired. In 1964 Cody succeeded him as the tenth archbishop of New Orleans. Rummel died on November 8, 1964, at the age of eighty-eight and was interred in St. Louis Cathedral in New Orleans.