Plessy v. Ferguson

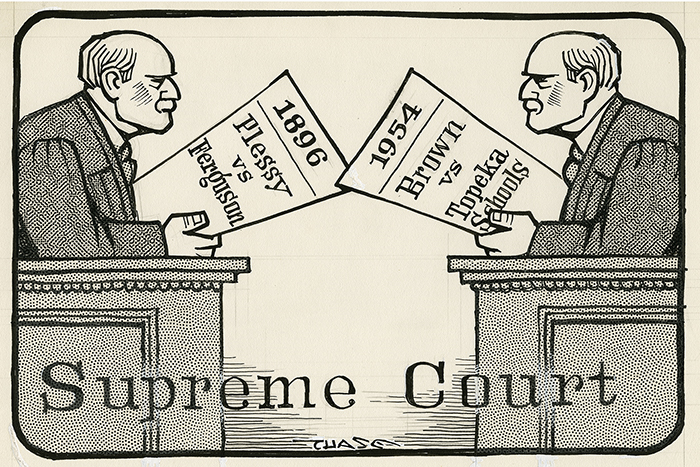

One of Louisiana’s most famous legal cases, Plessy v. Ferguson joins Dred Scott v. Sanford (1857) and Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas (1954) as key rulings on the US civil rights timeline.

The Historic New Orleans Collection

This 1977 political cartoon, "In 1892, we were here...," was published in a weekly series in the New Orleans States-Item newspaper. John Wilds wrote the columns, while John Churchill Chase created accompanying cartoon illustrations.

Plessy v. Ferguson, a US Supreme Court decision handed down on May 18, 1896, enacted “separate but equal” racial segregation as the law of the land for nearly six decades to follow, and it stands as one of three watershed civil rights cases in American history. The case was initiated from the 1892 arrest of New Orleanian Homer Plessy, who purposely tested the constitutionality of Louisiana’s segregated trains by boarding a whites-only passenger car. One of Louisiana’s most famous cases, Plessy joins Dred Scott v. Sanford (1857) and Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas (1954) as key rulings on the US civil rights timeline. The Supreme Court’s decision in Plessy sanctioned racial segregation on railroad trains and provided a legal umbrella for all Jim Crow laws that forced African Americans to live as second-class citizens. The Plessy case foreshadowed the civil disobedience methods of the Civil Rights Movements of the twentieth century.

Historical Background

The case made prominent the names of the plaintiff, Homer Adolph Plessy, and the defendant, Judge John Howard Ferguson, who ruled against him in 1892. Born Homère Patris Plessy in New Orleans on St. Patrick’s Day 1863, Plessy’s birth certificate identifies his parents as Adolphe Plessy and Rosalie Debergue, both of whom were listed on the certificate as free people of color born before the Civil War and residents of New Orleans. John Ferguson, who was born in 1838 on Martha’s Vineyard, Massachusetts, came to New Orleans after the Civil War and established a law practice in the city’s Uptown commercial district. He took the oath of office as Judge of Section A of the Orleans Parish Criminal Court on July 5, 1892.

The two men encountered one another roughly three months after Ferguson ascended to the bench. The lawsuit that brought them together represented an attempt to reinstate the legal barriers between the races that had begun to fall after the Civil War. The Thirteenth (1865), Fourteenth (1868), and Fifteenth (1870) Amendments emancipated the enslaved, granted equal citizenship rights, and prohibited the denial of suffrage rights based on race, respectively. By the late nineteenth century, however, the trend began to reverse after the post–Civil War Reconstruction government was disbanded following the Compromise of 1877.

In 1890 the Louisiana legislature passed the Separate Car Act, requiring black and white passengers to ride in separate railroad cars. In 1891, as a countermeasure, eighteen New Orleans residents formed the Comité des Citoyens, also known as the Citizens’ Committee for the Annulment of Act No. 111. Largely comprised of Republican activists, writers, lawyers, businessmen, former Union soldiers, and educators from New Orleans’s Black Creole elite, the Comité raised funds, held rallies, and hired attorneys to challenge the constitutionality of laws that segregated citizens by race on railroad trains.

Under guidance from the Comité, musician Daniel Desdunes of the Creole Onward Brass Band volunteered to defy the Separate Car Act on February 24, 1892, when he purchased a first-class ticket and boarded a designated whites-only car on the Louisiana and Nashville Railroad from New Orleans to Mobile, Alabama. The destination of another state was chosen specifically because of the belief that prohibiting his journey would violate the Commerce Clause of the US Constitution. Desdunes was ordered off the train and arrested, but his case never went to trial because the Louisiana Supreme Court ruled on May 25 in the unrelated Abbott v. Hicks case that the Separate Car Act did not apply to interstate passengers, therefore rendering the test moot.

Plessy volunteered to be the next agitator. On June 7, 1892, the thirty-year-old shoemaker arrived at the Press Street railroad yards near the Mississippi River. He purchased a ticket for the East Louisiana train bound for Covington and took his seat in the first-class coach. After the train’s conductor alerted detective Christopher C. Cain that a person of color was in the “whites-only” car, Plessy was arrested for violating the Separate Car Act.

Plessy Meets Ferguson

Plessy appeared before Judge Ferguson on October 13, 1892, in Case No. 19117, Homer Adolph Plessy v. The State of Louisiana, and pleaded not guilty to the charges of violating the Separate Car Act. On October 28, Plessy’s local lawyer, James C. Walker, argued that the Separate Car Act violated the Fourteenth Amendment, but Judge Ferguson ruled against him on November 18, 1892. “There is no pretense that he [Plessy] was not provided with equal accommodations with the white passengers,” the judge stated. “He was simply deprived of the liberty of doing as he pleased, and of violating a penal statute with impunity.” In December 1892 the Louisiana State Supreme Court, presided over by Francis Nicholls, upheld Ferguson’s decision.

The US Supreme Court

Plessy hired attorney Albion Winegar Tourgée to argue his case before the US Supreme Court on April 18, 1896, in Case No. 210, Plessy v. Ferguson. Segregation’s primary effect, Tourgée proffered, “is to perpetuate the stigma of color—to make the curse immortal, incurable, inevitable.” The court issued its ruling on May 18, voting seven to one to uphold the Louisiana court’s decision. “We consider the underlying fallacy of the plaintiff’s argument to consist in the assumption that the enforced separation of the two races stamps the colored race with a badge of inferiority,” argued Justice Henry B. Brown, representing the majority. “If this be so, it is not by reason of anything found in the act, but solely because the colored race chooses to put that construction upon it.” John Marshall Harlan, the lone dissenting justice, replied, “The destinies of the two races, in this country, are indissolubly linked together, and the interests of both require that the common government of all shall not permit the seeds of race hate to be planted under the sanction of law. … The thin disguise of ‘equal’ accommodations for passengers in railroad coaches will not mislead any one, nor atone for the wrong this day done.”

On January 11, 1897, Plessy returned to Criminal Court in New Orleans, entered a guilty plea, and paid a fine of $25. After the Supreme Court’s decision, the Comité des Citoyens continued to maintain that segregation was unfair and unconstitutional. But the case set a precedent. Confident that the federal government would defer to the states on issues involving race, Louisiana and other southern states passed additional segregation laws. “Separate but equal” remained accepted doctrine until its repudiation in the 1954 Supreme Court decision Brown v. Board of Education.

More than one hundred years after the Plessy decision, the Crescent City Peace Alliance installed a historical marker at the site of Plessy’s arrest in New Orleans. Members of both the Plessy and Ferguson families attended a ceremony at the corner of Press and Royal Streets on February 12, 2009. In 2022, Governor John Bel Edwards pardoned Plessy for violating the Separate Car Act.