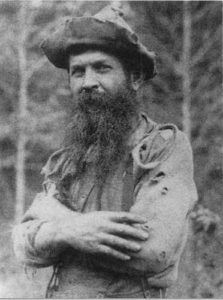

Ben Lilly

Louisiana hunter Ben Lilly was President Teddy Roosevelt's chief guide during his noted black bear hunt in 1907.

Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

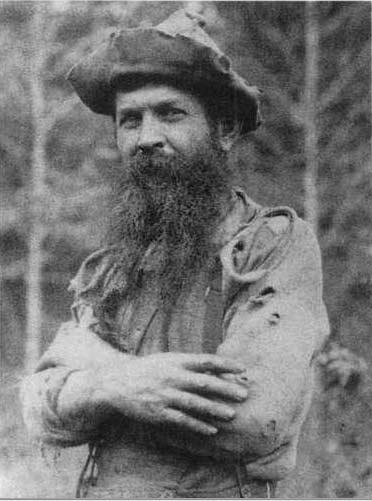

Ben Lilly. Unidentified

At the turn of the twentieth century, Louisiana’s vast natural resources—in the form of virgin forests and teeming wildlife—were besieged by commercial interests and others who lacked environmental consideration. In this era of diminishing wilderness, Ben Lilly emerged from the swamps of the state’s northeastern parishes to become a folk hero. His reputation as the best hunter of his day evolved as a result of his obsessive compulsion to kill bears and cougars. President Theodore Roosevelt hired Lilly as his chief guide during his noted Louisiana bear hunt. Ironically, Lilly’s successful efforts at stalking animals in Louisiana, and later out West, contributed to the loss of a lifestyle he cherished.

Early Life

Benjamin Vernon Lilly, one of seven children, was born in Wilcox County, Alabama, in the winter of 1856. His father, Albert, was a blacksmith and soon moved the family to Kemper County, Mississippi. Young Ben learned his father’s trade and especially relished the art of knife making. His parents, however, had loftier goals and sent him to a military academy in Jackson, Mississippi. Ben promptly ran away and was lost to his family for several years. His uncle Vernon Lilly, a well-to-do planter in Morehouse Parish, found Ben working as a blacksmith in Memphis, Tennessee, and offered him a job and eventually his estate if he would work the farm. Ben accepted the offer and his Louisiana life began.

In 1880, at twenty-three years old, Lilly married Lelia Bunckley. They had one son, Vernon, who died young. The couple soon divorced, and Lelia was later admitted to an insane asylum. Lilly married again in 1891, this time to Mary Etta Sisson (1867–1931). This marriage resulted in three children: Hugh, Ada Mai, and Beatrice Verna. The family lived on the outskirts of Mer Rouge.

Lilly ultimately concluded that he was not cut out to be a farmer. He dabbled in the cattle and timber businesses and commercial knife making, but he found none of these occupations satisfying. He discovered his passion in the Bonne Idee and Boeuf swamps after killing a bear with one of his knives. From that point forward, his life centered on the pursuit of large predators. Accordingly, in 1901, he transferred his property to his wife and children and walked out of their lives.

The Hunter

Lilly soon learned that he could make a living as a hunter, and he became adept at it. The US Bureau of Biological Survey hired him in 1904 to collect mammals and birds for its national museum. Over the years, he sold the agency many skulls and skins. From Louisiana he shipped a cougar, five black bears, seven red wolves, and two rare ivory-billed woodpeckers. His hunting prowess continued to improve even as his quarry diminished in numbers. In 1906 Lilly left Louisiana for the Big Thicket region of east Texas. There he was successful in killing a number of bears, and his reputation spread, even gaining the notice of an American president.

After a failed effort in Mississippi, President Theodore Roosevelt was eager to kill a black bear, as he later wrote, “after the fashion of the old southern planters.” He planned a hunt in northeastern Louisiana and summoned Lilly in Texas by telegram to be his chief guide. Lilly arrived at the hunting camp on the Tensas River in East Carroll Parish on October 5, 1907. For a week the hounds pursued and lost bears in the impenetrable canebrakes. Lilly suggested they pack up and move south to Bear Lake in Madison Parish. There, with Lilly as coach, the president finally succeeded in bagging his Louisiana black bear, one of sixteen subspecies of the American black bear.

The presidential bear hunt was the last of Lilly’s Louisiana adventures. He drifted back to Texas and into Mexico, always in pursuit of cougars and bears. He spent many years in Arizona and New Mexico, conducting predator control for ranchers and the government. Lilly’s last trip to Louisiana was a brief visit with his sister in Shreveport on August 11, 1920.

The Legend

Lilly’s legendary status was due in part to his peculiar looks and habits. President Roosevelt described him well:

There is a white hunter, Ben Lily [sic], who has just joined us who is a really remarkable character. He literally lives in the woods. … He had tramped for twenty-four hours through the woods, without food or water, and had slept a couple of hours in a crooked tree, like a turkey. He has a wild, gentle face, with blue eyes and full beard; he is a religious fanatic and is as hardy as a bear or elk, literally caring nothing for fatigue and exposure which we couldn’t stand at all. … He was particularly fond of the chase of the bear, which he followed by himself with one or two dogs; often he would be on the trail of his quarry for days at a time, lying down to sleep wherever night overtook him.

Lilly observed the Sabbath and would not raise a hand to work on Sunday. He never cursed, smoked, or drank alcohol or coffee. He was known to subsist for days in the wilderness with only a sack of cornmeal. Lilly preferred to sleep and eat outdoors even when amenities were available. Laden with bearskins and live cougar kittens, his brief and infrequent visits to towns only enhanced his enigmatic aura. Given the opportunity in a crowd, he was known to promote his own heroic folklore.

Lilly died at a ranch in Grant County, New Mexico, on December 17, 1936, near the age of eighty. His epitaph in the Silver City Cemetery reads, “Ben Lilly—Lover of the Great Outdoors.” By modern standards, the inscription would contradict his lifestyle of the relentless pursuit of apex predators, but it was appropriate to the times in which he lived. Monuments to Lilly have been erected in Mer Rouge and in New Mexico’s Gila National Forest. In 2013 the Ben Lilly Conservation Area was established in Morehouse Parish along Bayou Bartholomew.