Black Panther Party

The Black Panther Party briefly flourished in New Orleans as it brought a message of hope and upliftment to impoverished residents in the Ninth Ward.

The Historic New Orleans Collection

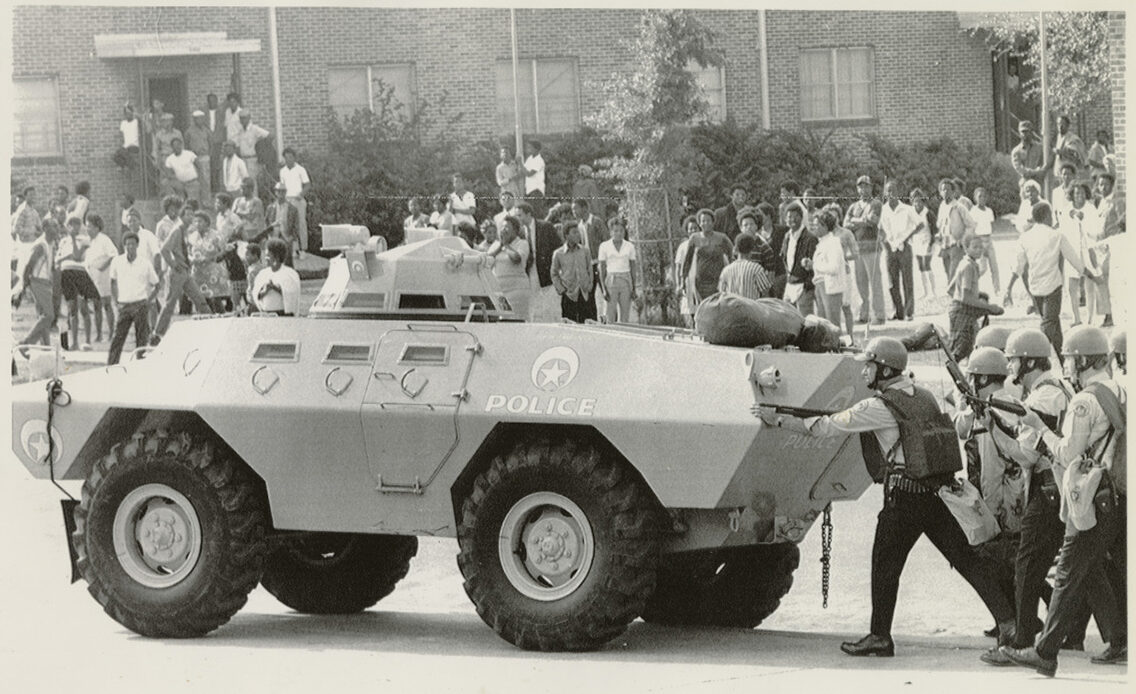

New Orleans Police Department with an armored vehicle outside of Black Panthers headquarters in the Desire housing project

The Black Panther Party briefly flourished in New Orleans in 1970 as it brought a message of hope and upliftment to impoverished residents in the Ninth Ward. Violence associated with the national organization, as well as fears of potential urban unrest in the Crescent City, prompted law enforcement and political leaders to aggressively go after the group, breaking its stronghold in the city.

Organization Origins

The struggle for racial equality in the 1950s and 1960s resulted in many changes, including the burgeoning of the Black Power movement. Influenced by a variety of Black nationalist groups, including the Universal Negro Improvement Association, the Nation of Islam, and the Deacons for Defense and Justice, the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense was born in Oakland, California, in October 1966 under the leadership of Bobby Seale and Monroe, Louisiana, native Huey P. Newton. The Black nationalist organization sought to uplift and protect its community while embracing a Marxist-Leninist revolutionary worldview. When the group’s members took advantage of open carry laws and boldly brandished firearms on Oakland streets, the Panthers quickly became the target of city officials. As an organized entity the California variant of the Black Panthers did not last long, as aggressive law enforcement efforts resulted in the arrest of the organization’s leadership following frequent armed confrontations with police. FBI head J. Edgar Hoover weighed in on the controversy and supported ending the Panthers using all tools at his disposal to undermine the credibility of Black nationalist organizations and by keeping its leaders imprisoned on federal charges. Despite the cloud of violence surrounding the Panthers, the group’s message resonated with those tired of racial injustice, police brutality, and the absence of opportunity. In particular, supporters gravitated toward the organization’s promise of protection and sense of community secured by an armed presence that ran counter to the non-violent protest efforts of civil rights leaders like Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Frequent local, state, and federal law enforcement interference stymied the Panthers’ larger initiatives and dwindling membership numbers led to the group’s 1982 dissolution.

Black Panthers in New Orleans

Communities bowed by the weight of racial discrimination became fertile territory for the spread of the Black Panther movement. In Louisiana the Desire Housing Project in the primarily Black Ninth Ward section of New Orleans proved amenable to the message of empowerment championed by the Panthers. Headed by Ronald Ailsworth, Steve Green, and Harold Holmes, the National Committee to Combat Fascism, the recruiting arm of the Panthers, arrived in the Crescent City in May 1970 and filled a void in a community where opportunity was scarce, law enforcement excesses typical, and the legacy of racial discrimination ever-present. The Panthers established a permanent headquarters on 3542 Piety Street, just outside the Desire Housing Project. Despite their revolutionary rhetoric, the Panthers were most known to the city’s Black inhabitants for outreach programs, especially free breakfasts for school-age children. The group also championed the demands of New Orleans’s impoverished citizens, whom it served through various community action programs, including the popular Free Breakfast Program for neighborhood youth. Although their membership was never large, the Panthers earned the respect of the residents of Desire, offering them hope at a time when opportunity proved scarce.

Relationship with Law Enforcement

The Panthers promoted a message of upliftment, and its members criticized law enforcement and challenged the capitalist system. City officials took note. New Orleans Police Superintendent Joseph Giarrusso, eying the Panthers’ emergence in the city, took his concerns regarding the group to the mayor, Maurice Landrieu, whose 1970 election was partly secured by overwhelming Black support. An ardent integrationist, Landrieu grew alarmed by the prospect of armed guerilla and revolutionary activity taking place in New Orleans. Landrieu and other city leaders recognized the potential power of Panther ideas in a community home to some of the state’s poorest and most disenfranchised citizens. Despite police concerns and the lawlessness associated with the Panthers in other American cities, the group in New Orleans had threatened no violence and was fast becoming a fixture in the Ninth Ward.

As soon as the Panthers emerged in the city, law enforcement began infiltrating the organization to stay abreast of the group’s activities. Before long, two infiltrators were discovered and allegedly beaten by the group before they escaped. Panthers subsequently opened fire on police officers who arrived at the scene, sparking a crisis in the city. The Panthers barricaded themselves inside their headquarters as a law enforcement siege commenced. On Tuesday morning, September 15, 1970, the police, under the direction of new Superintendent Giarrusso, stormed the compound, ended the siege, and arrested numerous Panthers. During the standoff Mayor Landrieu apprised Louisiana Governor John McKeithen of the disturbance. The governor expressed his desire to keep the Panthers from getting a foothold in the state and applauded the aggressive police action.

The remaining leadership of the Panthers set up a temporary headquarters in an abandoned apartment in the Desire Housing Project next to the community center, where they continued the group’s outreach programs. On November 19, 1970, a law enforcement cadre comprised of more than two hundred individuals backed by a war wagon descended on the Desire Housing Project hoping to detain the remainder of the group’s leadership under the pretext that they were illegally occupying the vacant apartment they commandeered following the fall of their Piety Street headquarters. Hundreds of project residents blocked police access to the Panther headquarters, prompting a law enforcement withdrawal. The incident made national news and even spawned a visit from actress-turned-activist Jane Fonda. On November 25, police maintaining constant surveillance on the small group of revolutionaries holed up in the Desire Housing Project detained twenty-five Panthers attempting to flee the city in four cars rented by Fonda. A few days later law enforcement apprehended the remaining Panther leaders. With the group’s hierarchy in custody, the National Committee to Combat Fascism lost its direction.

Decline

Desire residents were sympathetic to the Panthers, especially following what they considered the heavy-handed police effort to dismantle the organization, which at least outwardly brought only positives to the community. The excesses of the New Orleans Police Department were well known to the city’s Black population. Reckless shootouts sparked by law enforcement with seemingly little concern for the safety of the uninvolved community, in turn, further framed the anti-law enforcement narrative surrounding the showdown and raised racial tensions. In the end the Panther presence in the Crescent City proved brief. With white and Black officials committed to preventing large-scale urban unrest in New Orleans, many supported marginalizing the perceived threat posed by the Panthers before it became an actual one.