Louisiana Women in the Civil Rights Movement

As early as the antebellum era, Louisiana women fought for the rights of African Americans in the abolitionist movement.

Amistad Research Center

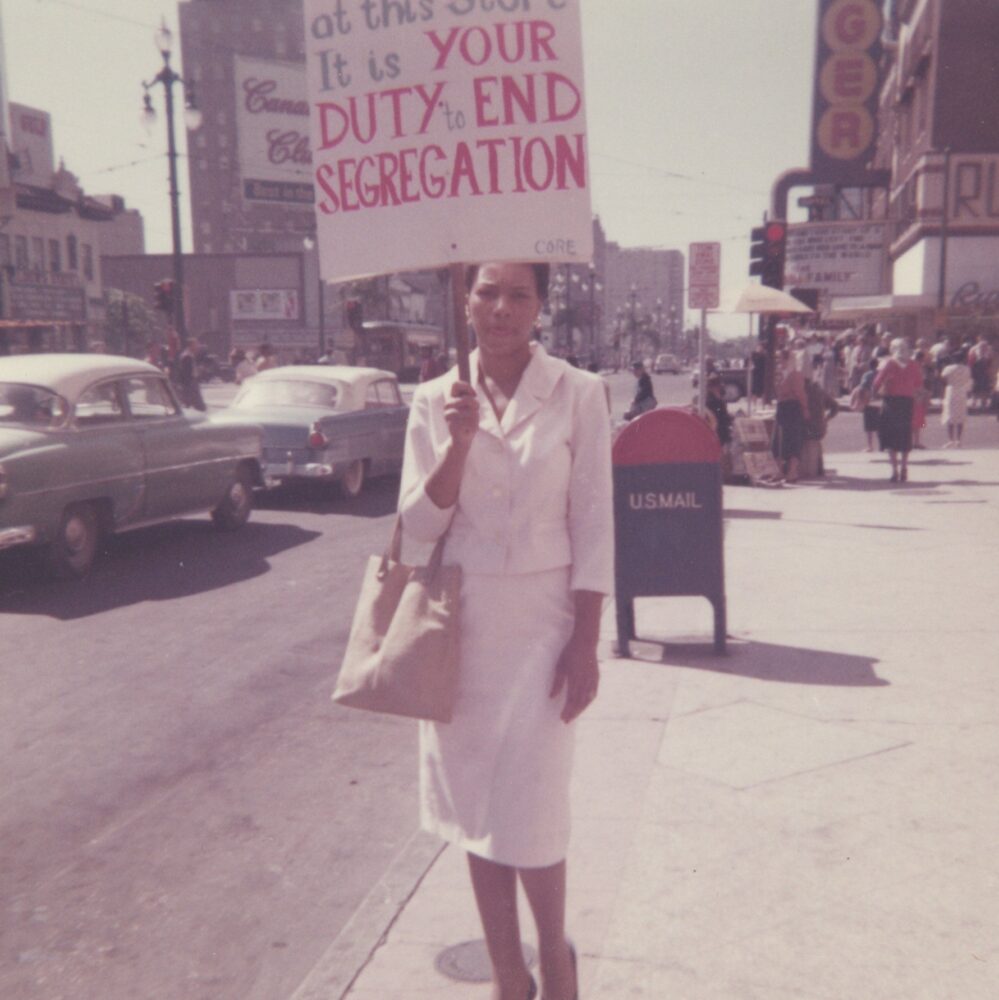

Doris Jean Castle picketing at the 1961 CORE protest of Woolworth’s and McCrory’s in New Orleans.

As early as the antebellum era, Louisiana women fought for the rights of African Americans in the abolitionist movement. In the late nineteenth century, when the US Supreme Court upheld the doctrine of “separate but equal” in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) and state legislators formally stripped Black people of any rights gained in the Constitution of 1898, Louisiana women again fought vigorously to secure Black people’s rightful place as citizens. Throughout the twentieth century, many Louisiana women, Black and white, recognized the unequal status of the races. They openly defied prescribed gender and racial roles by agitating for greater equality and an end to Jim Crow-era racism.

Though their numbers within formal civil rights organizations were significant, Louisiana women were not simply rank and file members. They participated in numerous test cases; joined and agitated through unions; integrated organizations and schools; registered to vote; sat-in at public facilities; escorted children to newly integrated schools; canvassed, housed, and fed civil rights workers; held voter education clinics in their homes; and taught in freedom schools. Women also organized, led, marched, demonstrated, and presided over major civil rights organizations. Doretha Combre, for example, was National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) state president in the 1950s. When the era of the modern civil rights movement waned, these women continued their community work in neighborhood improvement associations, poverty programs, and local educational systems.

Challenging Jim Crow

In the fall of 1924, New Orleans police arrested “Mrs. Beck,” an African American schoolteacher, for moving into a house that she bought on a block traditionally populated by white residents. In response, the NAACP challenged a residential segregation ordinance passed by the city earlier that September. Eventually, the Beck case was incorporated into a new case, Harmon v. Tyler, and combined with the case of Prudhoma Dejoie, who was arrested when she refused to stop construction on a house she purchased in a white neighborhood. The combined cases went to the US Supreme Court in 1927, where the justices reaffirmed the decision in Buchanan v. Warley (1917) regarding the illegality of residential segregation.

During the Great Depression and the New Deal era, Louisiana women actively participated in agricultural and domestic service unions at both the state and local levels. Although women performed much of the behind-the-scenes administrative and educational work, they also openly advocated for better pay and working conditions for farm women and domestics, free medical care, and a maternity insurance system. In West Feliciana Parish, for instance, husband-and-wife farmers Willie and Irene Scott organized the Louisiana Farmers Union with the support of their landlady, Sarah Towles Reed, a white political activist and union supporter. Reed, a New Orleans public school teacher, founded the New Orleans Public School Teachers Association in 1925 and then organized the union-affiliated New Orleans Classroom Teachers Federation (NOCTF). With her assistance, Black women in New Orleans formed a teachers’ union affiliated with Reed’s NOCTF, ultimately obtaining the same pay as white teachers.

In the 1940s and 1950s, Black and white women worked to create biracial organizations to achieve racial justice on behalf of Louisiana’s Black population. The New Orleans branches of the Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA) and the League of Women Voters (LWV) were among the first in the state to include Black women among their ranks. In addition, Louisiana women challenged racial segregation through the courts. In 1940, for example, a group of African American New Orleans public school teachers filed suit, demanding pay equal to that of their white counterparts. The Louisiana Supreme Court ruled in favor of the teachers in October 1943 and ordered the complete equalization of salaries in New Orleans.

Through the 1950s, African American women challenged Jim Crow on a daily basis through spontaneous actions and confrontations at work and in public facilities such as buses and streetcars. In 1953, African American citizens in Baton Rouge staged a boycott of the city’s public bus system. As in the more famous boycott that followed in Montgomery, Alabama, women played a crucial role in this protest. In addition to boycotting the buses by the thousands, Black women organized and drove for a free ride system, raised money, and participated in mass rallies. In so doing, they helped sustain the Baton Rouge bus boycott, which ultimately provided a model for the boycott in Montgomery.

School Integration

In late 1959, after Judge J. Skelly Wright ordered the integration of the Orleans Parish public school system, a group of elite white women, affiliated with the Urban League of Greater New Orleans, the League of Women Voters, the Young Women’s Christian Association, and the National Council of Jewish Women, came together to challenge the city’s white segregationist power structure. Together they formed Save Our Schools (SOS), arguably the most important and influential civil rights organization in New Orleans. Black and white mothers bravely subjected their children and themselves to reactions from staunch segregationists, often encountering violent mobs that gathered daily outside the integrated schools. These women also distributed information, lobbied before the state legislature, raised funds, and garnered media attention in an attempt to sway public opinion in favor of integration.

When the New Orleans schools finally integrated in November 1960, SOS members Betty Wisdom, Peggy Murison, Kit Senter, Mary Sand, and Anne Dlugos organized car pools to escort mothers and children to and from the schools. The women also testified before the state legislature about the importance of school integration, raised money on behalf of the parents who lost their jobs because of the controversy, held public meetings, and lobbied local businesses for support. Through it all, they were harassed, spat upon, and attacked; though they received death threats and had crosses burned on their lawns, they persevered.

The Movement Intensifies

A new phase of the civil rights movement began when students led sit-ins to protest segregation in public facilities. Louisiana women were in the vanguard during the first Baton Rouge sit-ins. Similarly, in New Orleans, a group of students from colleges and universities across the city formed a Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) chapter. At the outset, women dominated the CORE group: Oretha Castle Haley; Julia Aaron; Doretha Smith; sisters Shirley, Jean, and Alice Thompson; Ruthie Wells; Katrina Jackson; and Sandra Nixon were among the initial members. Through the fall of 1960 and for the next four years, CORE demonstrated at public facilities across the city, conducting sit-ins and protests at local lunch counters, restaurants, hotels, and movie theaters. CORE members also picketed stores on Canal Street, New Orleans’s major shopping district, and held marches to protest the city’ segregated conditions.

CORE members experienced an additional boost when the organization’s leaders announced their intention to embark upon the Freedom Rides from Washington, DC, to New Orleans. After an infamously brutal attack in Anniston, Alabama, New Orleans CORE members met and decided to continue the rides. Within days, a busload of New Orleans CORE members, mostly female rank and file members, arrived in Montgomery. Doris Castle, Julia Aaron, Sandra Nixon, Jean Thompson, and Shirley Thompson joined Diane Nash and members of the Nashville Student Union for the second phase of the rides. When arrested, all refused to pay their bail and began serving thirty- to ninety-day jail terms.

When CORE began preparations for its first voter education project in rural Louisiana, women again rose to the challenge in 1962. Women such as Miriam Feingold, Oretha Castle Haley, Mary Hamilton, Alice Thompson, Shirley Thompson, and Jean Thompson proved to be integral and influential members of CORE’s Louisiana field staff. Additionally, at the grassroots level, women such as Charlotte Greenup, Odette Harper Hines, and Josephine “Mama Jo” Holmes supported the voter education project by housing and feeding staff members, holding clinics in their homes, and joining civil rights organizations. Women registered to vote and participated in meetings and mass demonstrations in greater numbers than men. In addition, a number of women from northern colleges and universities elected to work in dangerous rural areas of the state as field secretaries, staff members, canvassers, and organizers.

In the 1970s and 1980s, female activists familiar with organizing strategies utilized their knowledge to help implement Lyndon Johnson’s antipoverty initiatives. Women dominated the neighborhood civic and improvement associations and outnumbered men on executive committees, often comprising a majority of organizational membership. Despite the obstacles that many women confronted because of their gender, the struggle for racial equality provided them with a unique opportunity to expand their traditional roles. Louisiana women challenged traditional notions of women’s work as they sought to improve conditions for Black residents in their communities. Indeed, in Louisiana, women’s participation was vital to the success of the civil rights movement not only in the state, but also in the movement writ large.