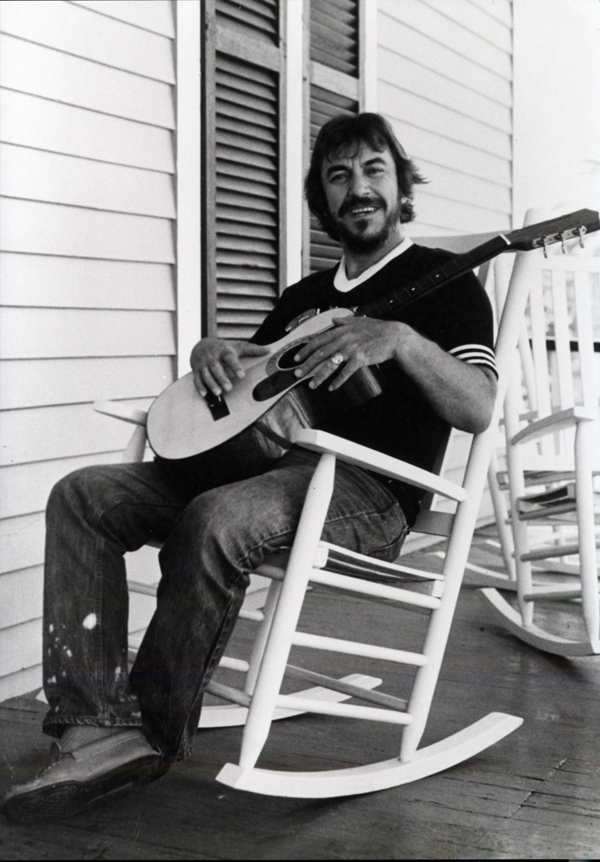

Bobby Charles

Bobby Charles made enduring contributions to the overlapping genres of rhythm and blues, rock and roll, and swamp pop, as both a recording artist and a songwriter.

Louisiana State Museum

Bobby Charles.

Bobby Charles, a native of Abbeville, in Vermilion Parish, was born Robert Charles Guidry in 1938. He made enduring contributions to the overlapping music genres of rhythm and blues (R&B), rock and roll, and swamp pop as a recording artist and songwriter. Musicians who recorded hit versions of Charles’s songs include Bill Haley and His Comets (“See You Later, Alligator,” 1956), Fats Domino (“Walking To New Orleans,” 1960), and Clarence “Frogman” Henry (“But I Do,” [also known as “I Don’t Know Why,”] 1961). While Charles’s rendition of “See You Later, Alligator” rose to Billboard magazine’s Top Twenty chart, the latter two songs peaked in the Top Ten.

Musical Background

Unlike most successful songwriters, Charles did not play any instruments. Nor could he read music. His unorthodox yet effective technique consisted of writing down lyrics, with a vague yet intuitive sense of melody, and then getting colleagues to provide chord progressions and conventional song structure through trial-and-error. As Charles recounted, “Willie [Nelson] one time said, ‘Well, what is the right chord?’ And I said, ‘I don’t know, just play all the chords you know, and I’ll tell you when you hit the right one.’ ”

Charles’s early influences included Cajun music, country music à la Hank Williams, and R&B by such songwriters/recording artists as Ray Charles, and Percy Mayfield. As a teenager Charles was deeply inspired by Fats Domino, Lloyd Price, and Guitar Slim.

Early Career

In 1955 Charles wrote the street slang–inspired “See You Later, Alligator.” A music store owner in Crowley loved the song and called Chess Records in Chicago so that Charles could sing it over the phone. Chess immediately sent Charles to record in New Orleans with the expert audio engineer Cosimo Matassa. At this juncture Charles dropped his Cajun last name, reflecting the prevalent pressure during the ’50s to assimilate into mainstream America by downplaying ethnic identity.

The Chess Records roster consisted primarily of Black artists. Charles never sent Chess any publicity photos, and Chess executives had assumed that Charles was Black too. At that time some Black radio stations would immediately stop playing an artist’s records if that artist, to their surprise, turned out to be white. But “See You Later, Alligator” was already selling well, and, despite some consternation, Chess decided against pulling it off the market.

Instead Chess sent Charles on tour with some of the label’s major Black artists, including the pioneering rock and roll guitarist Chuck Berry. Some white audiences in the South were angered by the multi-racial billing, and violence ensued. “Chuck and some other people in the band,” Charles recalled “…saved my damn life more than once.”

When a record is released, songwriters receive royalties starting with the first record sold, while artist royalties kick in once recording expenses are recouped. As both the artist and writer, Charles anticipated substantial compensation from “See You Later, Alligator” but he soon learned that getting full and even fair payment was highly problematic. Feeling exploited—“I was getting ripped off left and right,” he recalled—Charles withdrew from the music business and became notoriously reclusive. During the mid-1960s he briefly recorded for the Shreveport-based Jewel/Paula Records, but that relationship soon soured, too, over money.

Recording in Woodstock, New York

Charles next surfaced in 1971 in Woodstock, New York, a town famed for a major music festival held nearby in 1969. Charles fell in with several members of the popular rock group, The Band. With their help, and accompaniment by the expatriate New Orleanian, Mac Rebennack, known professionally as Dr. John, Charles recorded a 1972 self-titled album.

Charles’s songwriting had changed considerably from his glib couplets penned in the 1950s; he dwelled instead on his profound disaffection from society: “Hangin’ out with the street people, they got it down, hangin’ out with the street people, drifting from town to town … Who’s gonna work, make the economy grow, if we all hang out in the street? Well, I don’t know, and I don’t care, just as long as it ain’t me …” This stance, combined with his outspoken disdain for record executives, earned Charles admiration, among musicians, as an uncompromising antihero.

Years later his self-titled album, retroactively revered as a classic, was reissued as a CD with elaborate packaging and extensive liner notes. But soon after its original release, Charles clashed with Bearsville Records, and he withdrew from music again. A second album recorded for Bearsville, featuring the same stellar accompanists, remains unreleased. In 1976 Charles reconnected with The Band for the group’s farewell concert, which was filmed by the noted director Martin Scorsese for a 1978 documentary entitled The Last Waltz. Charles refused to sing the song that Scorsese demanded, so his performance footage was not used. He can be heard, however, on The Last Waltz soundtrack.

Later Years

During the next decade Charles returned to South Louisiana. He mellowed somewhat and began recording more often, releasing six well-received albums between 1988 and 2010, the year of his death. With age, Charles came to be regarded as a wise elder whose reclusiveness enhanced his status as a musical legend. Such high regard is evidenced by two albums paying tribute to him, by Beth McKee and Shannon McNally respectively, and by frequent performances of his songs by various bands based in Lafayette.

Charles’s ultimately forlorn and eloquently understated song “I Hope” was recorded in 2021 by his long-time swamp pop colleague Tommy McLain. In 2022 McLain’s then-new album received considerable international acclaim. In interviews McLain was quick to give Charles lavish praise as a major figure in Louisiana’s musical pantheon.