Camp Ruston

Camp Ruston was one of five large internment facilities established in Louisiana to house captured Axis soldiers transported to the United States during World War II.

Louisiana Tech University Special Collections.

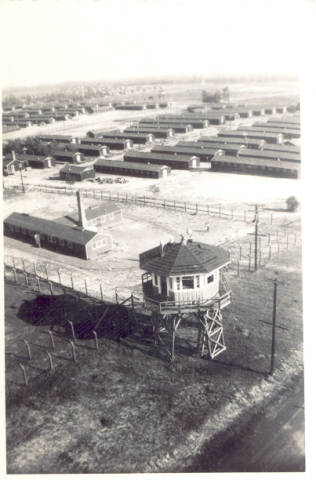

Ariel view of Camp Ruston, ca. 1942-1945.

At the outbreak of World War II, Camp Ruston, which would become one of the largest prisoner-of-war (POW) camps in the United States, opened in North Louisiana. Located not in its namesake of Ruston but seven miles northwest on the edge of Grambling, then a small African American village, the internment camp housed mostly German prisoners, with smaller numbers of French, Austrian, Italian, Czech, Polish, Yugoslav, Romanian, and Russian soldiers.

Camp Ruston was one of five large internment facilities established in Louisiana to house the hundreds of thousands of captured Axis soldiers who were transported to the United States. After a survey of several candidate sites in North Louisiana, the US War Department selected the Grambling location, in part, because of its proximity to the Vicksburg, Shreveport, and Pacific Railroad—a necessity for the efficient movement of men and materials. Officials bought seven hundred fifty acres via eminent domain from the landowners for $24,200 and promised the return of the property after the war. Local contractor T. L. James & Company built the camp on a standardized plan that included rows of tar paper–covered housing units for the prisoners, a housing and administrative complex for the American guards, three water wells, a water tower, kitchens, mess halls, latrines, a chapel, a laundry, and recreation areas. The POW officer compound was separated from that of the enlisted men. A tall wire fence punctuated by guard towers surrounded the entire camp. Construction cost $2.5 million, and the camp was activated on Christmas Day 1942.

Boot Camp and Wartime Prison

Until the first prisoners arrived in August 1943, the camp served as headquarters of the Fifth Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC) Training Center. More than three thousand WAACs received basic training at the facility. The first trainload of prisoners to arrive at Camp Ruston consisted of three hundred men from Field Marshal Erwin Rommel’s renowned Afrika Korps. The most important prisoners included the crew of the German submarine U-505. After the vessel and its code book were captured near Cape Verde in the Atlantic Ocean on June 4, 1944, the crew was placed in isolation at Camp Ruston. The men were even denied visits from the International Red Cross in order to keep the Germans from learning that their secret codes had been compromised. German prisoners with strong Nazi sentiments and those considered non-Nazis were usually sent to separate camps to help maintain order. Camp Ruston was considered a non-Nazi facility. In October 1943 the camp reached its peak occupation with 4,315 prisoners.

The American captors observed the 1929 Geneva Convention on the treatment of POWs, and legitimate prisoner complaints were rare. Meals were adequate, and medical care was provided. When not involved in routine camp work—such as cleaning and cooking—or on remote details, physical recreation was encouraged. Baseball, basketball, tennis, boxing, and especially soccer were favorite sports. A theater group produced musical comedies for the men. Music was popular in the camp and resulted in a POW orchestra, band, and choirs. The POWS created art and practiced hobbies like woodworking. The prisoners were proactive in continuing their own education. Competent instructors from within their own ranks taught secondary school and college-level classes in languages (including English, French, and Arabic), math, business, chemistry, physics, history, geography, and art. They had access to books from nearby Louisiana Polytechnic Institute (now Louisiana Tech University). The American government, in a subtle effort to instill democratic values in the prisoners, provided relevant movies, books, and magazines to further this cause.

Camp Ruston also provided labor and administrative support to several branch camps, including ones in Bastrop, Lake Providence, Tallulah, and West Monroe. POWs worked mainly in the farming and timber industries but also on public works, such as road building. For their labor, prisoners were paid in scrip that could be spent in the camp’s canteen to purchase coffee, cigarettes, beer, toiletries, and reading material.

Closure and Aftermath

The last prisoners left Camp Ruston for repatriation in early February 1946. The camp was shuttered the following June. Decades after their incarceration at Camp Ruston, former POWs would recall their lives in the North Louisiana hill country and commonly remark that their experiences led them to support a postwar democratic government in their own countries.

Camp Ruston had no happy ending for the former owners of the camp’s property. Bowing to political pressure, the federal government reneged on its promise to return the land and instead sold it to the state government. A tuberculosis sanatorium occupied the site from 1947 to 1958, and it later became the Ruston Developmental Center, a medical facility for disabled people. Two of the camp’s original buildings remain and were listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1992.

In 2007 the documentary German POWs in Louisiana: The Camp Ruston Story was produced for Louisiana Public Broadcasting. The program featured archival film and photographs as well as reenactments of camp events. The Special Collections Department at Louisiana Tech University contains documents and artifacts related to Camp Ruston, and the Museum of Science and Industry in Chicago, where the captured U-505 is displayed, also has records related to the crew and their internment in North Louisiana.