POW Camps in Louisiana

During World War II, Allied commanders sent more than twenty thousand prisoners of war to camps in Louisiana.

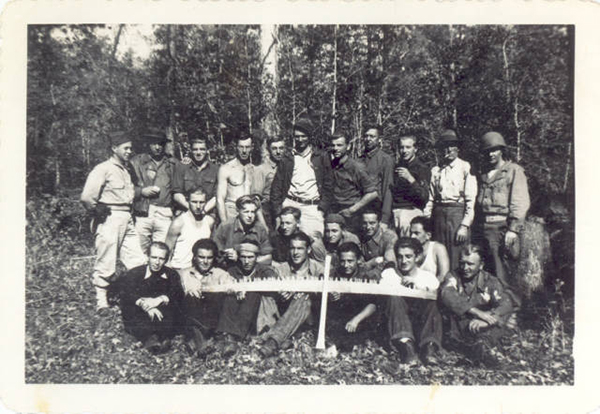

Louisiana Tech University, Prescott Memorial Library Special Collections

Portrait of POWs, ca. 1942–1946.

During World War II the battlefield successes of Allied Forces fighting German armies in North Africa and later on the European continent resulted in a complex logistical problem: what to do with thousands of captured enemy troops. To provide security and adequate food and housing required by the Geneva Convention of 1929, Allied commanders decided to send prisoners of war (POWs) to the United States. More than five hundred POW camps were built across America to house more than four hundred fifty thousand enemy soldiers for the duration of the war. With five base camps and more than forty satellite camps holding more than twenty thousand prisoners, Louisiana was an active participant in this phase of the war effort. The five Louisiana base camps were Camp Ruston (Lincoln Parish), Camp Claiborne (Rapides Parish), Camp Livingston (Rapides and Grant Parishes), Camp Polk (Vernon Parish), and Camp Plauche (Orleans Parish).

Camp Design

Base camps were built on a standardized design and modified as necessary to function on each geographic site. They usually included rows of tar paper–covered housing units for the prisoners, a housing and administrative complex for the American guards, mess halls, water wells, kitchens, latrines, a chapel, laundry facilities, a parade ground, and recreation areas. The POW officer compound was separated from that of the enlisted men. A tall wire fence punctuated by guard towers surrounded the entire camp. Satellite camps were smaller versions of the base camps. Land for the camps was acquired by eminent domain from local landowners or by repurposing other government property.

Camp Life as POWs

Most POWs in Louisiana camps were German from Field Marshal Erwin Rommel’s Afrika Korps along with some Italians and conscripted men from other European countries. A few were Japanese. The majority of German POWs were neither professional soldiers nor advocates for Hitler or his war. Generally, their attitudes resulted in peaceful camp environments. However, a small percentage of POWs were devout Nazis who were segregated from the other German soldiers because of their efforts to coerce them to be uncooperative. Regardless of their POW status, all the men were still considered soldiers. They followed military rituals such as reveille (waking up) and lights out, and they marched in formation. Military rank was recognized with the highest-ranking German officer at each camp in charge of the POWs there.

POW letters, diaries, and postwar interviews reveal that most were generally satisfied with their condition in the camps. Food and housing were adequate, and compared to life in a war zone, they were well off and safe. Army physicians supervised health care often assisted by contracted local physicians and POW doctors and dentists. POWs were given the opportunity to practice their religious traditions in most cases. To ensure compliance with Geneva Convention rules, the International Red Cross made frequent camp visits.

Recreational and entertainment opportunities were important to POWs and varied according to camp size and location. Soccer, volleyball, cards, and chess were popular activities along with arts and crafts. Some camps had radios and phonographs. Professional and amateur POW performers conducted plays and concerts. Camp Polk had a thirty-eight-piece orchestra that played homemade and donated instruments. Weekly movies were routine with American westerns being a favorite genre. Most camps had libraries, some with several thousand titles. Many POWs avoided idle time by enrolling in available classes, including languages, music, art, business, math, and science. Only the base camps provided extensive programs, a frequent complaint of those assigned to the satellite camps.

POW Contributions to Allied Efforts

Across the United States hundreds of thousands of able-bodied POWs made significant contributions to the Allied war effort in the form of labor. They eased a critical manpower shortage when many American men were overseas in the military. POWs in Louisiana were an important part of that force. Louisiana legislators had lobbied for the establishment of POW camps in the state because of labor shortage concerns of their constituents—mainly farmers. The shortage, a result of a high percentage of men serving in the armed forces or working out of state in well-paying defense industry jobs, threatened sugarcane production in southern parishes and cotton farming in northern parishes. Internment camps relieved the shortage by requiring that enlisted prisoners perform agricultural and other labor, usually on a seasonal basis. Enlisted prisoners were required to work, but officers were not compelled to do so. Workers earned the equivalent of about eighty cents a day for an eight-to-ten-hour workday, six days a week. Payment was made in scrip that could be exchanged for basic necessities at the camp commissary.

POWs came from all walks of life and possessed many trades and talents that were applied accordingly. Tailors repaired uniforms. Mechanics rebuilt vehicles. Accountants worked as clerks, and general laborers worked in factories and sawmills. Some built public works projects such as roads and buildings. In 1944 one group helped sandbag the overflowing Red River. The most valuable work by POWs in Louisiana was provided to farmers. Especially at harvest time, farmers were desperate for help to gather crops. Many satellite camps were located in agricultural areas where POWs picked cotton and cut rice and sugarcane.

Anecdotes and Aftermath

The history of POW camps in Louisiana includes interesting anecdotes unique to the state.

One of the most notable groups of POWs comprised the crew of the German submarine U-505. After the vessel and its code book were captured near Cape Verde in the Atlantic Ocean in June 1944, the crew was placed in isolation at Camp Ruston. The men were even denied visits from the International Red Cross in order to keep the Germans from learning that their secret codes had been compromised.

America’s first Japanese POW, Kazuo Sakamaki, arrived at Camp Livingston in 1942. He was the only surviving crewman of a mini submarine involved in the attack on Pearl Harbor. Sakamaki was captured after abandoning his boat when it struck coral reefs and sank.

POW escape attempts were uncommon because most prisoners realized they were thousands of miles away from their homes, with the likelihood of a sustained getaway near zero. Kurt Richard Westphal, housed in the Bastrop satellite camp, was an exception. He escaped the Morehouse Parish camp in August 1945 and was recaptured in Hamburg, West Germany, in 1954.

After the war most of the Louisiana POWs were soon repatriated even though some complained that they were unduly held until the 1945 crop harvest was completed. A few remained in the United States or returned to make their lives here. Others came back for camp reunions in Louisiana and elsewhere, an indication of their memorable days in an historic era.