Cercle Harmonique

Members of the Cercle Harmonique held séances and received messages from the spirit world in support of Black rights and social equality.

Courtesy of Earl K. Long Library, University of New Orleans

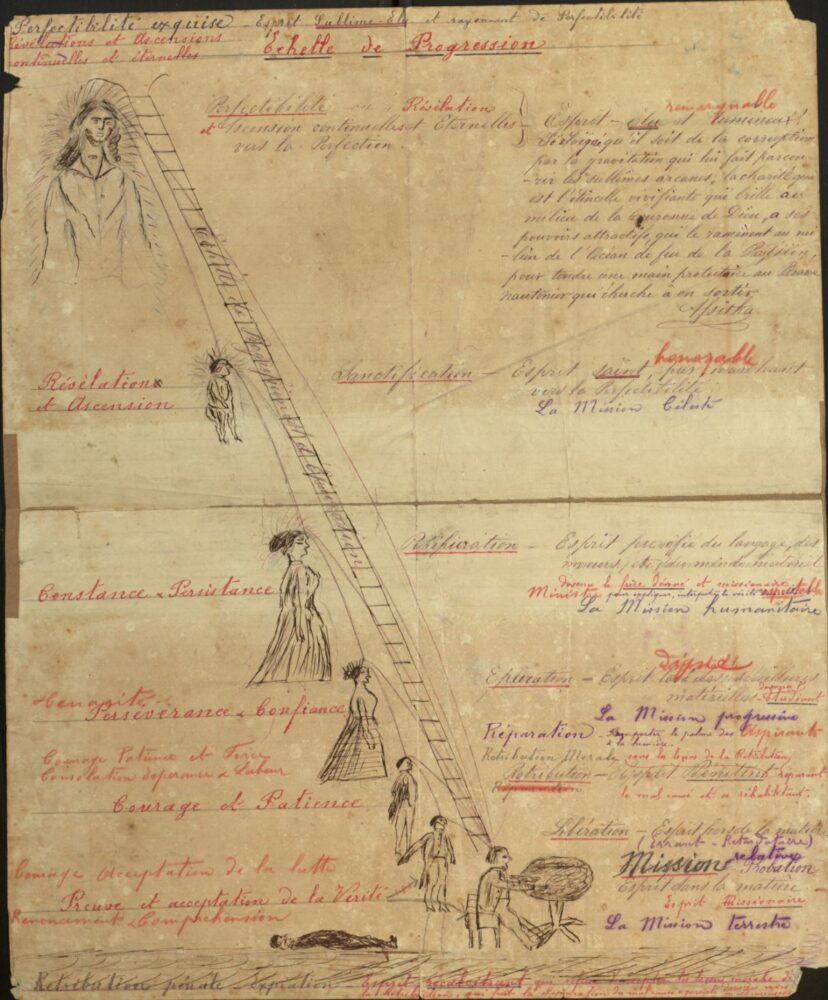

Échelle de Progression by René Grandjean

The Cercle Harmonique (French for “Harmonic Circle”) was a group of Afro-Creole men who practiced Spiritualism in New Orleans from 1858 until 1877. The religious movement known as Spiritualism began in 1848 in the small town of Hydesville, New York, near Rochester, New York, when two young girls allegedly began to communicate with the spirits of the dead. Spiritualism quickly spread across the United States and beyond in England and France, and the practice of a séance became a widespread leisure and/or religious experience. Spiritualism spiked in popularity in the wake of the Civil War as the nation grappled with widespread death. The Cercle Harmonique’s most active years of practice also took place after the Civil War, during the years known as Reconstruction. The Cercle Harmonique’s practice fused religion with politics, as many of the messages they received encouraged Black rights and social equality.

The community was small, typically with seven members at a séance. The main leaders of the Cercle Harmonique came from free, mixed-race families with Afro-Caribbean roots. As such, these men had some economic stability, received good educations, came from Catholic backgrounds, and were politically active. The main leader of the Cercle Harmonique was Henry Louis Rey, who served in the Louisiana Native Guards during the Civil War and in the Louisiana House of Representatives afterward. Rey’s Spiritualist mentors included a woman named Soeur (Sister) Louise, whose last name has been lost to history, and J. B. Valmour, a local Black Creole blacksmith and healer who practiced with Rey until his death in 1869, at which point he became a spirit guide for the group. Other members of the Cercle Harmonique were similar to Rey in terms of background and activism. In addition, both Rey and François “Petit” Dubuclet, the secondary leader of the group, came from mixed-race families who were slaveowners, making their own political activism for Black rights all the more significant.

The group’s structure was informal. A few members were spirit mediums, those individuals who could communicate with the spirits of the dead, while others helped that communication process. Their séance meetings began with the reading and discussion of previously received messages to establish harmony around the séance table. That harmony then enabled the medium to connect the group to the spirit world. The group met multiple times a week for séances and recorded the messages they received. When the group concluded in 1877, they had amassed thousands of pages of spirit messages. The séance records were kept by René Grandjean, whose father-in-law was a member of the group. Grandjean donated them to the Special Collections department of the University of New Orleans’s Earl K. Long Library.

The pantheon of the dead who visited the Cercle Harmonique was extensive. It included deceased family members and friends, as well as famous figures: Napoleon Bonaparte, abolitionist John Brown, Presidents George Washington, Abraham Lincoln, and Thomas Jefferson, Pocahontas, Jesus, Saint Vincent de Paul, Confucius, and Haitian revolutionary Toussaint Louverture. The overwhelming majority of the messages were transcribed in French, with a few in English, suggesting that both the Spiritualists and the spirit world were multi-lingual.

The Cercle Harmonique’s practice of communicating with the dead was religious and political. They received numerous messages about what the spirits called “the Idea”— a concept that emphasized equality, humanitarian progress, and harmony. The Idea meant that the Afro-Creole Spiritualists had a responsibility to work during their material lives and make the world a better place. The spirits informed the Cercle Harmonique that God had intended for the Idea to reign in the world of the living but that greed hindered it. If the Spiritualists could find ways to push back against human avarice, then the corrupt, material world could be more like the ideal, egalitarian spirit world they admired.

The Cercle Harmonique would ultimately fail in their quest to make the world a more harmonious place. The years of Reconstruction that followed the Civil War, 1865 to 1877, were ostensibly an attempt to bring the southern states back in line with American values of liberty and democracy. However, they were also years of violence. The 1866 Mechanics Institute Massacre, also known as the New Orleans Race Riot, and the so-called Battle of Liberty Place in 1874 were two tragic events in which white supremacist terrorists attacked Black New Orleanians and their burgeoning rights. According to the Cercle Harmonique, the spirits of the dead lamented this violence, and some of the slain returned in spirit form to encourage the group to continue its pursuit of equality.

In the aftermath of Liberty Place, the Cercle Harmonique began to disband. The René Grandjean notes indicate that the street battle made séance participants wary of meeting. Another reason for disbandment was that the séance participants were likely disappointed that the spirits’ hopes for progress had not materialized. Though Rey was alone, the spirits reportedly reminded him that they remained with him and supported him. The final recorded message arrived in November 1877 from the spirit of an unnamed friend who encouraged Rey to have confidence in the future. 1877 was also the year that Reconstruction came to a close. It was clear that the nation failed in its southern goals. Instead, many who opposed Black equality regained political control across the region. For the Cercle Harmonique, the end of Reconstruction signaled the end of possibility. There was no way to remake the nation in line with the spirits’ Idea.