Reconstruction

The post-Civil War period in US history is known as the Reconstruction era, when the former Confederacy was brought back into the Union.

Courtesy of The Historic New Orleans Collection

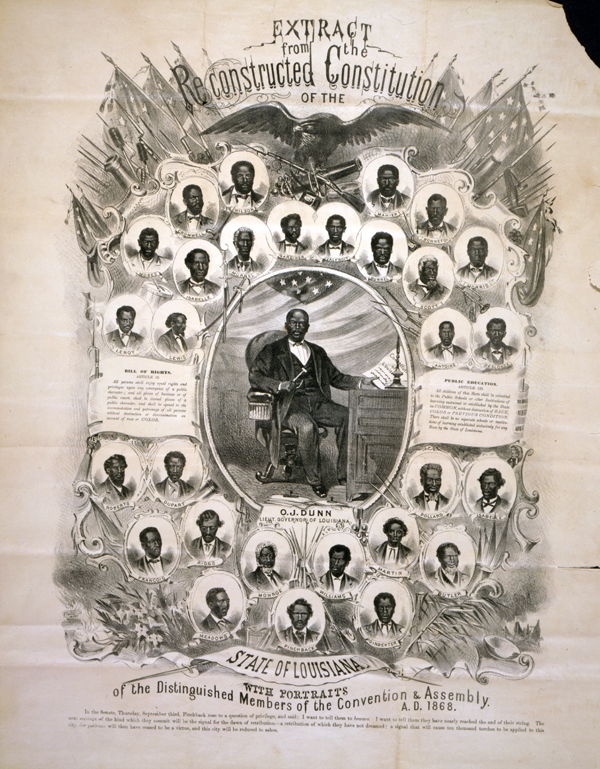

Louisiana Legislators in 1868. Unidentified

Reconstruction comprises the post-Civil War period in US history together with the federal policies that were implemented during that time to bring secessionist states back into the Union and to determine the status of former Confederate leaders and formerly enslaved people in the South. The politics of Reconstruction profoundly affected life in Louisiana, but because so much was at stake, it also played a disproportionately large role in shaping national opinion and federal policy toward the defeated South after the Civil War. Within the context of the region, Louisiana was an enormous prize. It was home to New Orleans, the South’s largest and most prosperous city and the crucial juncture between the commerce of the vast Mississippi River Valley and the rest of the world. And the countryside of the state featured some of the richest and most productive soil in the nation.

Louisiana also held out the promise of being equally fertile ground for the growth of Republicanism in the South. Louisiana had been a bastion of the Whig Party before the war, was home to protectionist-minded sugar planters, and enjoyed a comparatively large and well-educated free Black population. For these reasons, the Republicans fought with singular tenacity for control over the state. Defeated white southerners, on the other hand, were just as unwilling to meekly forfeit dominion over a society where they had once ruled. Such conditions guaranteed that the struggle for control of Louisiana would be particularly intense. Indeed, it is no wonder that Reconstruction lasted longer in the Louisiana than it did anywhere else, spanning the fifteen-year period between the spring of 1862 and the early months of 1877.

Wartime Reconstruction, 1862–1865

Although only the southern portion of Louisiana, including New Orleans and Baton Rouge, fell under the sway of the federal government during the Civil War, events in occupied Louisiana had a large impact on social and political policy of wartime Reconstruction in the South and the nation. President Abraham Lincoln believed there was a deep reservoir of southern unionism and desired the speedy return of seceded states to the Union. As a consequence, he established his Ten Percent Plan, under which a Confederate state might rejoin the Union once 10 percent of its free white men had sworn their loyalty. Occupied Louisiana became the scheme’s first proving ground when Lincoln ordered General Benjamin Butler to hold elections in New Orleans during the fall of 1862 in order to fill the two seats in the US House of Representatives districts that lay within the occupied territory.

Despite its many flaws and critics, Lincoln’s plan served as the basis for all wartime electioneering in Louisiana. This included gubernatorial and state legislative elections held at the behest of General Nathaniel Banks, which resulted in the inauguration of Michael Hahn as governor in March 1864, and the reestablishment of the state legislature in the new wartime capitol of New Orleans. Later that year, delegates from occupied Louisiana drafted a new state constitution, which led to the first meaningful debate over many of the key issues that would later dominate the Reconstruction era, including Black suffrage and public education. The underlying conservatism of the resulting document, however, bred discontent among the state’s radical leadership. More tragically, a clause that allowed the convention to reconvene in order to make amendments set in motion a series of events that would lead to postwar bloodshed.

The war years also led to an awakened Black political awareness in Louisiana. Not only did the state boast a large, educated, and prosperous free Black population, it was already organized around fraternal orders and trades. The first Black-run daily newspaper, the bilingual Tribune founded by the Afro-Creole physician Dr. Louis Charles Roudanez, appeared in New Orleans in 1864. Louisiana also supplied the largest number of soldiers to the US Colored Troops, a key element in forging Black political consciousness during Reconstruction.

Presidential Reconstruction, 1865–1867

The elevation of former planter James Madison Wells to the office of governor in March 1865, combined with the end of the war and Lincoln’s assassination, dramatically altered the path of Reconstruction in Louisiana. Though he had been a unionist and a fair-weather supporter of Radical Republicanism, Wells saw in President Andrew Johnson’s proclamation of pardon and amnesty an opportunity to build a new political coalition out of returning Confederates and conservative southern unionists such as himself. Wells proved unable to control what he had created, however. The new statewide elections that the governor ordered held in November 1865 resulted in the election of an almost entirely Democratic legislature that was devoted to enacting a most reactionary program. Abetted by President Johnson’s leniency, the newly reconstituted state government set about passing laws such as the Black Codes and other laws designed to compel the speedy return of formerly enslaved people to agricultural labor. By the early months of 1866, Radical Republicans and other advocates of universal suffrage faced grave danger from conservative violence, which culminated in the Mechanics Institute Massacre of 1866.

The riot came about when those who had crafted the state constitution of 1864 invoked the clause that allowed them to reconvene and make changes to the state’s governing document. Louisiana Radicals believed that the federal government, seeing its victory in the war slipping away, would uphold their legal authority to assemble and back their bid to introduce universal suffrage as an issue at this convention. What they did not realize was that the police and volunteer firemen of New Orleans would descend upon the meeting and murder more than thirty of their number. Along with a violent outbreak in Memphis earlier in the year, the melee in New Orleans proved influential in rallying northern support behind Radical political candidates, and as such, played a crucial role in empowering the Radical ascendancy in the fall 1866 congressional elections.

The Radical Ascendancy in Louisiana

In March 1867, over President Johnson’s veto, the new US Congress passed the first of four federal Reconstruction Acts and paved the way for the liquidation of the governments in Louisiana and nine other southern states then being controlled by former Confederates. In addition to effectively disfranchising all those who had been in support of the rebellion, these acts placed Louisiana into a military district with Texas and established guidelines for the creation of a new state government that included ratification of the recently passed Fourteenth Amendment. By eliminating the reactionary government that had formed under Andrew Johnson’s “Presidential Reconstruction,” the Radical ascendancy created an enormous political vacuum in Louisiana and ushered in a prolonged era when men with competing visions of the future battled for control of the state.

At the direction of General Philip Henry Sheridan, the military commander of the district, Louisianans set about crafting a new state constitution in the winter of 1867–1868. The document that emerged was quite revolutionary and provided for equal citizenship, voting rights for Black men, equal public accommodations, and public education. Balloting for new state officeholders and the constitution’s ratification by the people took place in April, resulting in the election of Republicans Henry Clay Warmoth, an Army veteran and early advocate of universal suffrage, as governor, and Oscar J. Dunn, an African American, as lieutenant governor.

The Warmoth Era, 1867–1872

Although he was only twenty-six years old when he took office, Warmoth had proven himself an estimable political operator and understood well the temperament of Louisianans in 1868. A witness to the Riot of 1866, one of Warmoth’s first deeds was the creation of the Metropolitan Police. While the Metropolitans were initially conceived as a force capable of maintaining order in the state capitol of New Orleans, their policing powers extended to surrounding parishes and their duties to the preservation of Warmoth’s government. This heavily armed body played an important role in the dramatic events that unfolded over the next nine years.

For the most part, disaffected whites had stayed out of the state electioneering in early 1868, and instead cast their gaze toward the upcoming presidential elections to take place in the fall. Believing that a national Democratic victory would snuff out Radical Reconstruction, militarized political clubs mobilized across Louisiana in the summer of 1868 with the objective of delivering the state for the Democratic ticket of Horatio Seymour and Frank Blair. In rural parishes, such activity led to the formation of the Knights of the White Camellia (KWC), a group many have likened to the Ku Klux Klan, which had little presence in Louisiana during Reconstruction. In actuality, the Knights were far more like their urban counterparts in New Orleans, such as the Seymour Knights and Crescent City Democratic Club—political clubs organized along military lines for the purpose of intimidating Republican voters, often violently. The KWC and similar organizations helped deliver Louisiana’s vote to Seymour and Blair, though President Ulysses S. Grant’s overwhelming national victory nullified their ambition to overthrow Radical rule. Moreover, the paramilitary violence during the election, both in Louisiana and elsewhere, inspired the newly elected Congress to pass the first of the Enforcement Acts, which were designed to empower the federal government to use the military to combat political insurgency in the South.

Political Factionalism

For decades historians of Reconstruction have portrayed the politics of 1868–1877 as a binary struggle between Republicans and conservative Democrats. In reality, widespread factionalism reigned in the Pelican State, creating a broad and fluid political spectrum that divided Louisiana’s Republicans and Democrats alike and undermined efforts at both social and economic progress.

Factionalism among Louisiana Republicans flowed from the fact that the party attracted men who were often at cross-purposes. On the one hand, the national party’s promotion of universal suffrage and civil rights legislation appealed to the overwhelming majority of freedmen as well as some idealistic white Louisianans. Yet on the other hand, some conservative white southerners believed that in Republicanism lay the best vehicle for restoring their class to a position of prosperity and political relevance, while others saw opportunity for profit and careerism in the power vacuum created by the Radical ascendancy.

Thus, Louisiana’s Republicans fell into three basic groups. The first and the most powerful was the Custom House Ring, which enjoyed the support of the national Republican Party led by President Grant. In an era before income taxes, when duties supplied the majority of the nation’s income, few civil service appointments reflected greater political favor or more potential for graft than that of collector of customs. Grant named his brother-in-law, James B. Casey, as collector at the port of New Orleans. Casey, along with US Marshall Stephen B. Packard, led the Custom House faction and controlled lucrative federal patronage in the state. The second group coalesced around the charismatic leadership of Henry Clay Warmoth. The governor’s control over state patronage and the Metropolitan Police allowed him to pose a formidable obstacle to Custom House hegemony. Yet both the Warmoth and Custom House factions recognized that neither was powerful enough to maintain control over the party without the support of the state’s third bloc of Republicans, the newly enfranchised Black voters. The need to respond to the aspirations of its Black constituency often forced the Republican Party to pursue a more egalitarian course than it might have otherwise done. This impulse was by turns the party’s greatest strength and largest liability.

Those who battled against federal Reconstruction efforts—the so-called Redeemers—were also deeply divided. While they were overwhelmingly white and native to either Louisiana or other southern states, their number included many northerners who had come to Louisiana after the Civil War to seek prosperity in southern agriculture and industry. The social and economic stability promised by the restoration of white conservative rule appealed to these individuals, because their plans for financial success hinged on the availability of a plentiful and obedient labor force. Yet disagreements over the acceptability of various political and social changes divided the Redeemers. At the most reactionary end of the spectrum stood Louisiana’s Bourbon Democrats, who rejected most forms of Black civil rights and political agency. By the start of 1869, however, many white southerners had come to reject the Bourbon strategy as impractical and had correctly identified such belligerence as the motive behind the passage of the federal Reconstruction Acts. These individuals, who considered themselves conservative Democrats, or Reformers, disassociated with the national Democratic Party name and advocated a limited acceptance of Reconstruction measures, including a recognition of the permanence of Black political participation. Yet like most white Americans of the era, the conservatives rejected Black social equality. The Reformers’ stronghold was in New Orleans, whereas the Bourbon Democrats dominated Louisiana’s countryside, though neither could make an exclusive claim on either region.

Historians have long characterized Warmoth’s reign as governor as one that embodied many of the evils of Reconstruction. Critics writing at the turn of the twentieth century accused Warmoth of committing enormous fraud against the people of Louisiana, selling bogus railroad bonds, extending corrupt patronage, and chartering the notorious Louisiana Lottery, among other wrongs. Modern historians fault Warmoth for his conservatism and basic devotion to white supremacy. There is no doubt that he was a willing and active participant in the graft of the Gilded Age, and that he retreated considerably from the egalitarian views that he had once espoused when he began seeking the Republican nomination for governor in 1867. Warmoth believed that by courting the conservative Democrats into a centrist Republican party, he might be able to build an enduring political legacy. In this he was remarkably successful, and by 1870 demoralization in Democratic ranks had reached an all-time high. In the end, Warmoth was toppled not by reactionary southerners but by jealous Republican rivals in the Custom House Ring.

Warmoth’s friendliness to former Confederates and his stinting progress on civil rights enabled the Custom House faction, led by Packard, to woo Warmoth’s African American lieutenant governor, Oscar J. Dunn, into their fold. Because of his deserved reputation for integrity, Dunn was among the most popular political figures among Black Louisianans during Reconstruction, and he had great influence over the sizable Black vote. By the summer of 1871, the Custom House faction had also co-opted the support of other Republican legislators who had once belonged to the Warmoth camp, including unsavory figures like Speaker of the House George W. Carter, a former Confederate officer who owed his post to Warmoth. With Carter’s help, Packard plotted to impeach Warmoth and place Dunn, who he believed would act as a reliable puppet, in the governor’s office. The Custom House faction also enlisted the help of disgruntled Bourbon Democrats who hated Warmoth because of his success in dividing white southerners politically.

Packard’s scheme collapsed, however, when Dunn died unexpectedly before a vote on impeachment could take place. What happened next characterized the tragic-comic tendency of the Republican party in Louisiana to undermine its credibility by engaging in self-destructive behavior. Believing that President Grant would back whatever they did, the Custom House Ring persisted in its efforts to impeach Warmoth. When they were bested by the governor at every turn, Speaker Carter and the Custom House-loyal legislators abandoned the state house and set up a rival legislature in the Gem Saloon in New Orleans’s French Quarter. In an effort to ensure a quorum at this irregular gathering, Packard, in his capacity as US Marshall, dispatched deputies to bodily transport legislators to the saloon while other deputies arrested Warmoth and key members of the Metropolitan Police. This farcical plan backfired, however, when one of the deputies killed an uncooperative legislator. Seizing the opportunity, Warmoth quickly bonded out of jail and dispatched the Metropolitan Police to the Gem Saloon to arrest Carter and the recalcitrant Custom House ringleaders. Warmoth then convened an emergency session of the legislature where Pinkney Benton Stewart (P. B. S.) Pinchback, a fair-weather Black ally of Warmoth and rival of Oscar J. Dunn, became lieutenant governor of the state.

Although Warmoth survived this attack by the Custom House group, he would never again retain full control over Louisiana’s Republican party. The governor soon split with Pinchback over the contentious issue of equal public accommodations, and made a more significant break with the Custom House faction and President Grant in 1872 by heading the splinter Liberal Republican movement in the state. Ultimately, Warmoth came to endorse a Fusionism campaign made up of Bourbon Democrats, conservative Reformers, and liberal Republicans. No longer in control of the Metropolitan Police, the lame-duck Warmoth was finally removed from office, making Pinchback the only man of color to serve as governor of a southern state during Reconstruction. His term lasted thirty-five days.

The gubernatorial election of 1872 proved a turning point in Louisiana’s Reconstruction, because its outcome served as the basis for the unparalleled discord that would follow for the next four years. The Redeemer camp, which had been driven into complete disarray first by the Radical ascendancy and then by Warmoth’s appeal to conservative Democrats, faced serious obstacles in fielding a viable candidate. The Bourbon wing of the Democratic Party was at its weakest point at any time during Reconstruction, and the conservative Democrats were largely divided between a Reform Party and liberal Republicanism. Only in July did these factions make an uneasy alliance under the Fusionism banner, nominating the Bourbon John McEnery of Ouachita Parish for governor and a liberal Republican from New Orleans by the name of Davidson Bratfute Penn for lieutenant governor. Meanwhile, the Custom House faction nominated William Pitt Kellogg for governor. Kellogg, an Illinoisan, had come to Louisiana as collector of customs in 1865 and had been selected by the state legislature in 1868 for the US Senate. His running mate was Caesar C. Antoine, an Afro-Creole businessman and politician from New Orleans.

The Kellogg Era, 1873–1877

Fraud and controversy marked the 1872 gubernatorial election at all levels. Both sides engaged in measures designed to eliminate the count of their competitor while inflating their own tally. In the end, however, balloting would be less relevant to the outcome than control over the returns. As governor, Warmoth had signed legislation that gave the chief executive enormous control over counting the votes, but his loss of control over the party led to the emergence of rival returning boards. Ultimately, a Republican-controlled judiciary decided which board’s total would be counted, leading to the elevation of Kellogg. While it is possible that Kellogg had indeed received more votes, his means of ascent undermined his legitimacy in Louisiana and eroded support for national Reconstruction policy in the North.

Believing that the federal courts or the US Congress might overturn Kellogg’s victory, the Fusionists set up a rival legislature in New Orleans at the Odd Fellows’ Hall. Competing inaugurations soon led to competing appointments for statewide offices, which in turn led to violent confrontations all over the state. The first clash came in March when McEnery called upon a citizens’ militia to overthrow the state Republican government in New Orleans. The Metropolitan Police quickly subdued this disorganized uprising and subsequently broke up the Fusionist legislature, arresting several of its members, including future governor Murphy J. Foster.

Several weeks later in Grant Parish, however, an uglier scene unfolded when a struggle between rival claimants to the office of parish judge blew up into the Colfax Massacre, the bloodiest single outbreak of racial violence during Reconstruction. When a Black militia attempted to sustain Kellogg’s appointee and maintain control over the Grant Parish courthouse in the town of Colfax, white mobs descended upon them and killed a hundred or more Black men. The damage to Republican aspirations did not stop there. Prosecuting the killers under the federal Enforcement Acts led to a broader legal disaster. In United States v. Cruikshank (1875), the US Supreme Court concluded that the federal government had overstepped its authority with the Enforcement Acts, effectively undermining their meaning. With the demise of these laws went all hope that rural Republicans in the South might have of using the army to preserve their safety. Once again, events in Louisiana had proven essential to national outcomes.

The summer of 1873 also witnessed the most unusual if short-lived efforts in biracial political cooperation during Reconstruction. The Unification Movement began in New Orleans as a cooperative effort between elite Afro-Creoles who were being left out of Kellogg and Packard’s Republican faction and white moderate businessmen who yearned for a peaceful end to Kellogg’s regime. Their pronouncements were perhaps the most advanced thinking on race to appear anywhere during Reconstruction and resembled closely what Congress would enact almost a century later in the Civil Rights Act of 1964. A lack of support in New Orleans and virtually no support among rural white Louisianans, combined with Republican sabotage, effectively doomed the Unification Movement before it could gain any meaningful following.

White Supremacy

With federal Reconstruction policy waning in popularity around the nation, a weakening national economy, and the widespread belief in Kellogg’s illegitimacy, conservative and Bourbon Democrats concluded by 1874 that a violent overthrow of Republicanism in Louisiana might be tolerated. Devoted to this end, the first White League formed in Opelousas in April of that year. It was always something of an ad hoc organization, and neighboring parishes soon established their own chapters modeled loosely on Opelousas’s charter. Though the specifics varied considerably from location to location, the most tangible effect of the White League was to suppress the factionalism that had dogged conservative and Bourbon efforts at overthrowing Republicanism, and as a consequence, the League functioned as something of a coalition between moderates and hard-liners. White supremacy, particularly in social relationships, tied these groups together, as did the assumption that Black politics were generally corrupt politics. The ultimate goal of the White League was to overthrow Kellogg’s rule.

Resistance to the White League in northern and central Louisiana was ineffectual at best, but in the Republican stronghold of New Orleans, the Metropolitan Police stood as a significant obstacle to complete revolution. Under the leadership of a former Confederate colonel named Frederick Nash Ogden, and in concert with conservative Democratic political leadership, the White League began in the spring and summer of 1874 to train a militia that was capable of overthrowing the government. The inevitable collision occurred on September 14, 1874, in an event that participants would soon dub the Battle of Liberty Place. Following a mass rally around the Henry Clay statue on Canal Street, the White League assembled in a line of battle in what is today the Central Business District and headed toward Canal Street and a waiting contingent of Metropolitan Police.

The brief battle that ensued left more than thirty men dead and resulted in a complete rout of the Metropolitan Police. The White League pronounced McEnery and Penn its chief executives, and for three days the city remained in their hands. Only when federal troops threatened to use force to restore Kellogg did the White League relinquish control. Yet no White Leaguers were prosecuted for their actions, and the organization remained a powerful threat to Republican survival. More important, they had largely destroyed the Metropolitans as a fighting force. Only federal bayonets now kept Kellogg in power, and his opponents knew it. Reflective of the growing unpopularity of federal Reconstruction policy in the nation was the Democratic Party’s sweeping to power in the US House of Representatives in the fall 1874 elections, where it moved to further reduce appropriations to the army’s occupation of the South.

By the time the 1876 gubernatorial elections arrived, Louisiana was one of only three southern states where the Reconstruction-era Republican governments remained. The contest pitted Packard against Confederate war hero Francis Tillou Nicholls. Once again, widespread ballot fraud prevented an accurate tally of votes. Packard hoped that he, like Kellogg, could count on the support of the federal government to sustain his bid, yet national politics made this unlikely. In the presidential contest that year, Republican candidate Rutherford B. Hayes needed the electoral votes from the three “unredeemed” southern states in order to win. After Hayes met with delegates who represented the Democratic/Conservative forces in Louisiana, Florida, and South Carolina at the Wormley Hotel in Washington, DC, the basic outlines of the Compromise of 1877 took shape. In it, Nicholls supporters guaranteed that Louisiana’s electors would support Hayes’s presidential ambitions in return for a promise that the federal government would not support the gubernatorial aspirations of Packard and would withdraw troops from the state. The bargain, which was quite controversial at the time, effectively brought an end to federal Reconstruction efforts in the South. Once again, the actions of Louisianans had a direct impact upon the outcome of key national questions.

Reconstruction After 1877

Although many narratives mark 1877 as an end to Reconstruction, a number of the era’s key questions remained unanswered for another twenty years. Abandoned by many of their white Republican allies, Black Louisianans would continue to fight bravely for their political and social rights in the Redeemer era, but it would be a steady retreat culminating in the US Supreme Court’s ruling in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) and Louisiana’s “disfranchisement” constitution of 1898. Significant victories included P. B. S. Pinchback’s securing the charter for what would become Southern University in 1879. Meanwhile, the White League coalition split into warring factions almost immediately following the Compromise of 1877, creating a period of political turmoil that would pit conservative Reformers against the Bourbons for the rest of the century. The political corruption continued unabated. Not until the turn of the century, when Jim Crow became the law of the land and most Black Louisianans had been removed from the voting rolls, could the champions of white supremacy—mostly men who had been born during Reconstruction—claim victory.

Other Developments during Reconstruction

As important as politics are to the story of Reconstruction in Louisiana, it was also a period of crucial economic, legal, social, and cultural change. Despite many efforts at building railroads, fixing levees, and otherwise reestablishing the commerce and economic health of the state, the acrimony that characterized politics tended to blunt any meaningful progress. While valuable programs such as public education gained an important foothold during the era, the inability to establish a competitive east-west rail line combined with burgeoning competition from midwestern states meant that Louisiana lost some of its importance in the national and regional economy, a trend that would continue for many decades. Corruption certainly played a role, but the nearly constant political turmoil in Louisiana also scared away investment. From an economic standpoint, the Civil War and Reconstruction proved a setback from which the state has yet to fully recover.

With the destruction of slavery in Louisiana came the transition to free labor and a reappraisal of the relationship between Black and white Louisianans. In the early years of Reconstruction, the Freedmen’s Bureau assisted this process to varying degrees. In the state’s cotton-growing parishes, this ultimately meant a changeover to sharecropping and improved autonomy for freedmen. Although working on shares was difficult, the number of Black farmers who were able to save enough money to purchase land grew significantly during Reconstruction. In Louisiana’s sugar-growing regions, planters made a less smooth transition to a wage economy, as sugar cultivation did not lend itself to small-scale production. Recognizing their bargaining power, cane workers made several attempts to organize for better wages. Ultimately, the larger sugar planters would crush cane worker unrest in the Thibodeaux Massacre of 1887. Like Black politics, Black labor made many important gains during Reconstruction, only to see them slowly evaporate by the turn of the century.

Events in Louisiana during Reconstruction also contributed significantly to the legal foundations of the nation, particularly with regard to civil rights. The legal question of equal accommodations in places of public resort and transportation began during the war, with Black Union soldiers and the Star Car controversy, and continued throughout the era. Article 13 of the 1868 state constitution barred discrimination in places such as theaters and taverns, and Black Louisianans successfully sued in court for damages, establishing important legal precedent. Yet without question, the most pivotal action to originate in Louisiana during Reconstruction came to be known collectively as the Slaughterhouse Cases (1873). Intended to settle the question of the city’s authority to regulate slaughterhouses for the public well-being, the verdict ended up drastically limiting the reach of the Fourteenth Amendment to protect citizens against the actions of individual states.

Cultural changes also abounded after the Civil War. Mardi Gras, for instance, underwent a profound transformation during Reconstruction as a direct result of the troubled politics of the era. Left out of politics, white elites in New Orleans retreated to the private sphere, where they founded what are today the old-line Krewes of Rex, Proteus, and Momus. Their elaborate parades served both as public entertainment and a vehicle for political and social commentary. Indeed, Reconstruction was not only largely responsible for cementing the city’s devotion to Carnival, by 1872 it had become a major tourist attraction, drawing as many as 30,000 visitors from all over the nation.