Code Noir of Louisiana

The 1724 Code Noir of Louisiana was a means to control the behaviors of Africans, Native Americans, and free people of color.

The Historic New Orleans Collection

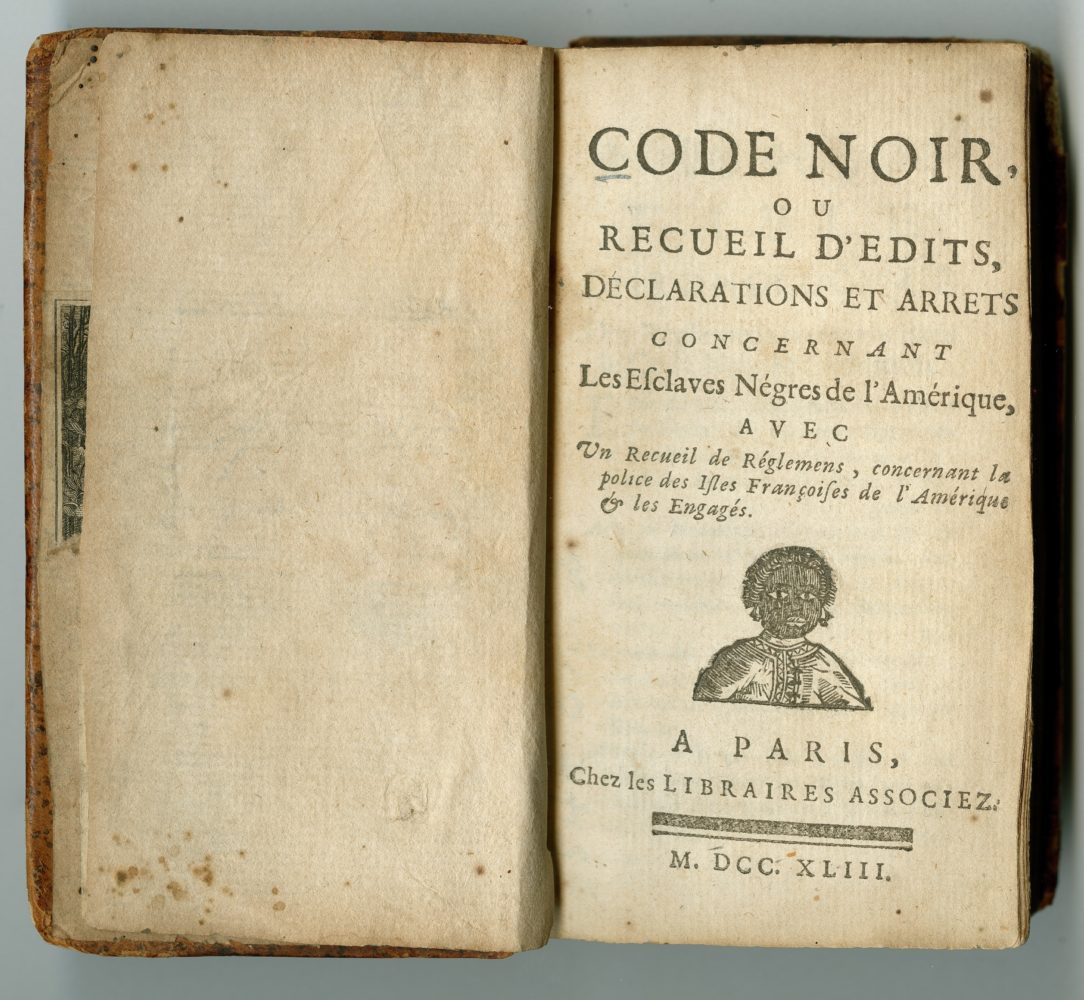

Code Noir of 1724. Paris: les Librairies Associez, 1743.

In 1724, the French government issued a version of the Code Noir in order to regulate the interaction of European-descended (blancs) and African-descended people (noirs) in colonial Louisiana. Portions of the first Code Noir (instituted in 1685 for the French colony of Saint Domingue) appeared in the second edition, though several alterations were made to account for the special circumstances of Louisiana. Enforcement of the Code Noir proved difficult throughout French colonial Louisiana, resulting in the cultivation of a brutal system of enslavement that nonetheless failed to control all forms of close contact between people legally identified as Black and white. Following the suppression of the Insurrection of 1768, the Spanish colonial regime replaced the Code Noir with legal measures of its own, though the influence of the French slave system remained noticeable into the nineteenth century.

The fifty-five articles of the Code Noir represented an attempt on the part of French officials to control the lives of people of European and African descent in colonial Louisiana. The first eleven articles refer to religious matters in the colony, including the expulsion of Jews, the recognition of Roman Catholicism as the only legitimate religion, and the mandate against interracial marriages and other kinds of métissage (racial mixing) between blancs and noirs. The remaining forty-four articles cover topics ranging from the obligations of masters (maîtres) to their slaves (esclaves), illegal activities and forms of punishment, the lack of legal rights afforded the enslaved, and rules for manumission (affranchissement). For example, enslaved people found guilty of illegally gathering in crowds were whipped for the first offense, and then branded with the mark of a fleur-de-lis after multiple offenses. In addition to lashes and branding, convicted runaway slaves had their ears cut off. Less severe penalties, usually in the form of fines, awaited whites who attempted to marry Black people, as well as the priests who conducted such marriage ceremonies.

The Louisiana Code Noir of 1724 differed from the Saint Domingue Code Noir of 1685 in several important ways. First, the Saint Domingue laws prohibited concubinage (living together out of wedlock) but permitted interracial marriages between Black and white people baptized in the Roman Catholic Church, while the Louisiana laws prohibited such marriages. Second, it was possible for owners of enslaved people of Saint Domingue to manumit their human property at their own discretion, while in Louisiana owners required the approval of the Superior Council. The Louisiana code also included more restrictive measures aimed at regulating the lives of free Black people and preventing the organization of maroon communities composed of runaway slaves.

Legislators of the Code Noir of 1724 intended for the laws to contribute to the cultivation of a colony that resembled ancien régime ideals of social order. Specifically, they expected to limit opportunities for manumission, reduce the level of métissage, and focus the power to inflict corporal punishment in the government and away from owners of enslaved people, all of which was meant to sharpen the racial division between Black and white people. The Code Noir of 1724, however, did little to account for the common practice of enslaving Native Americans in Louisiana, not to mention the near impossibility of preventing a large white male population composed of free, forced, and indentured settlers from interacting with free and enslaved Black people on a regular and intimate basis. Even more uncontrollable was the interaction between Native Americans and runaway slaves, a fact that contributed to events surrounding the so-called Natchez Revolt of 1729. Some priests continued to marry people of different races despite the legal mandate against the practice. It was also the case that some Protestants settled in French Louisiana despite the revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685 and the prohibition against the practice of Protestantism in the colony. Moreover, owners continued to punish their human property regardless of the code’s intention to allocate the power of punishment to colonial officials, often with even more brutal results.

The 1764 arrival of Antonio de Ulloa (1716–1795), the first Spanish governor of Louisiana, led to the demise of the French Code Noir and its replacement with a Spanish model for the regulation of Black-white relations. Ulloa upset the French Creole community of New Orleans when he permitted the marriage of a white Spaniard and an enslaved Black woman. The new governor also perturbed the local white population when he restricted the common practice of whipping enslaved people in the city of New Orleans, reportedly because the cries of whipping victims bothered his wife. Following the Insurrection of 1768, General Alejandro O’Reilly (1722–1794) reinstated the Code Noir, only to replace the French laws three months later with the laws of Castille and the Indies. Going back to the thirteenth century, Spanish laws associated with slavery tended to give the enslaved more rights than the French laws, including the right of an enslaved individual to purchase his or her own freedom. That being said, French planters in Spanish colonial Louisiana retained considerable influence over the lives and deaths of those they enslaved on their plantations. The membership of powerful French planters in the Cabildo (city council) also meant that the slightly more lenient Spanish slave codes often conflicted with customary modes of treating enslaved people in Louisiana.