Compromise of 1877

The Compromise of 1877 refers to an unwritten deal that settled the disputed 1876 US presidential election and ended congressional Reconstruction.

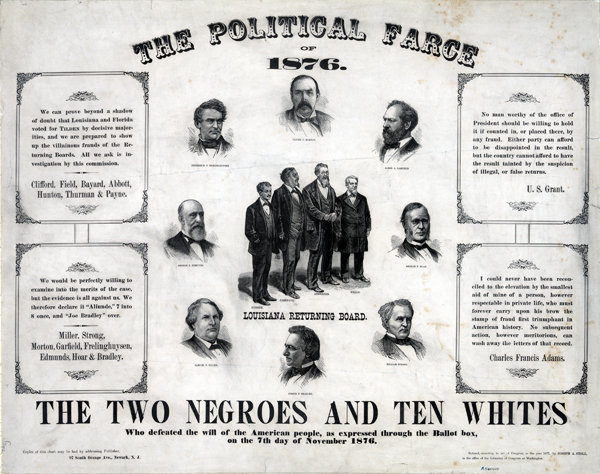

Courtesy of Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

A black and white reproduction of a political poster entitled “The political farce of 1876.”

The 1876 election year ended with both the presidential race and Louisiana’s gubernatorial election in dispute. Louisiana’s role in what became known as the Compromise of 1877 secured the White House for Rutherford B. Hayes, installed Confederate veteran Francis T. Nicholls as Louisiana’s governor, and ended federal occupation and Reconstruction in the state—along with any hope that African Americans would achieve equality under the law there in the coming decades.

The presidential campaign had pitted Hayes, Ohio’s Republican governor, against Samuel Tilden, New York’s Democratic governor. The campaigning was intense, as both candidates attempted to portray themselves as alternatives to the widespread corruption found in President Grant’s administration. Tilden outpolled Hayes by 250,000 votes, but then, as now, the winner was decided by Electoral College votes, not the popular vote, and Tilden came up one vote short. The Democratic nominee received 184 electoral votes, one fewer than the majority required by the US Constitution; Hayes had received 165. Twenty other electoral votes were in dispute in South Carolina, Louisiana, and Florida, where the Republicans’ Reconstruction governments still retained tenuous control over state governments. All three states submitted two sets of electoral ballots, one favoring each of the presidential contenders.

In Washington both Democrats and Republicans claimed victory. Under the Constitution, the ultimate solution rested with Congress, but neither the House of Representatives nor Senate could solve the problem. Democrats possessed a significant majority in the House, while Republicans controlled the Senate. The Twelfth Amendment instructed that “the President of the Senate shall, in the presence of the Senate and the House of Representatives, open all the certificates, and the votes shall be counted.” The amendment failed, however, to offer a remedy for conflicting certificates from the states. Democrats claimed that sole responsibility lay with the House, and the Republicans argued for the Senate.

In January 1877 the situation remained deadlocked. As the bitterness between the two parties intensified, politicians in Washington begin to talk about using force to solve the problem. Democratic governors in fifteen states talked about mobilizing National Guard units to install Tilden as president. Republicans, on the other hand, looked to Grant to activate regular army units on behalf of Hayes. Eventually, cooler heads prevailed. On January 18, 1877, both parties agreed to the creation of an Electoral Commission to certify the contested votes. This commission was composed of five House members (three Democrats and two Republicans), five Senate members (three Republicans and two Democrats), and five justices from the US Supreme Court (two Democrats, two Republicans, and one independent).

To all concerned, it now appeared that the problem could be resolved. On January 25, however, Justice David B. Davis, the independent, resigned from the commission and accepted an offer from Illinois Republicans to run for their party’s vacant Senate seat. Justice Joseph P. Bradley, a Republican appointee, filled his position. When, on February 8, 1877, Bradley confirmed Democratic suspicions by voting to certify Florida’s election returns for Hayes, the political sparks flew. Democrats from Northern states began talking about instituting a filibuster to prevent the certification of the electoral votes. Under the Constitution, on March 3, 1877, if there was no certified presidential victor, the Speaker of the House of Representatives would become president.

Louisiana, meanwhile, had its own constitutional crisis brewing. Democratic Civil War hero Francis T. Nicholls had opposed Republican carpetbagger Stephen B. Packard in the 1876 governor’s race, and both parties claimed a majority of votes and established governments. As the disputed presidential election was pondered in Washington, Louisiana Democrats—including Nicholls supporters E. John Ellis and E. A. Burke—helped broker a deal that put their man in office in Baton Rouge, pulled federal troops out of Louisiana, and delivered the presidency to the Republican Hayes.

Meeting in secret at Wormley’s Hotel in Washington, Northern Republicans and Southern Democrats hammered out an agreement on February 26, less than a week before the inauguration. As a result of this pact, often described as the Compromise of 1877, Southerners refused to back the filibuster efforts of Northern Democrats on Tilden’s behalf, thus insuring the selection of Hayes as president. In return, Hayes and leading Republicans agreed to remove federal troops from the three “unreconstructed” states, appoint a Southerner to his cabinet, support the expenditure of increased federal funds on internal improvement in these three states, encourage the construction of a transcontinental railroad with a terminus in the South, and have the president visit the South.

Almost immediately upon taking office, President Hayes began the process of fulfilling these commitments. Federal troops were removed from Florida, Louisiana, and South Carolina, effectively ending Reconstruction in those states; David M. Key of Tennessee was appointed postmaster general; railroad men began planning the construction of a southern link to the Pacific Ocean; the president crossed the Potomac for a short tour; and Southern states, especially Louisiana, began receiving increased funding for local improvements. Withdrawal of the federal troops from Louisiana essentially negated Packard’s claim to the governorship, which was based on votes from the newly enfranchised African American population.

Nicholls and other newly minted Southern Democratic governors, such as Wade Hampton in South Carolina and Richard Coke in Texas, came to be known as “Redeemer” governors because their rise to power, coinciding with the moderate Republican administration of President Hayes, snuffed out the influence of Radical Republicans and Reconstruction. The transition resulted in whites-only, one-party rule in Louisiana and across the South, which would remain in place for almost a century.

Conspicuously absent from the provisions of the Compromise of 1877, however, were safeguards for Southern freedmen. They were, in the words of Frederick Douglass, “left naked unto their enemies.” Before agreeing to the compromise that put him in power, Governor Hayes preferred oral promises from Southern political leaders that the civil rights recently extended to African Americans in the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments would be protected. The historical record reveals just how empty those promises were.