Coushatta Baskets

The skills of the Coushatta Tribe’s contemporary basket weavers have elevated this centuries-old utilitarian craft to a highly valued art form showcased in private and museum collections nationwide.

The Historic New Orleans Collection

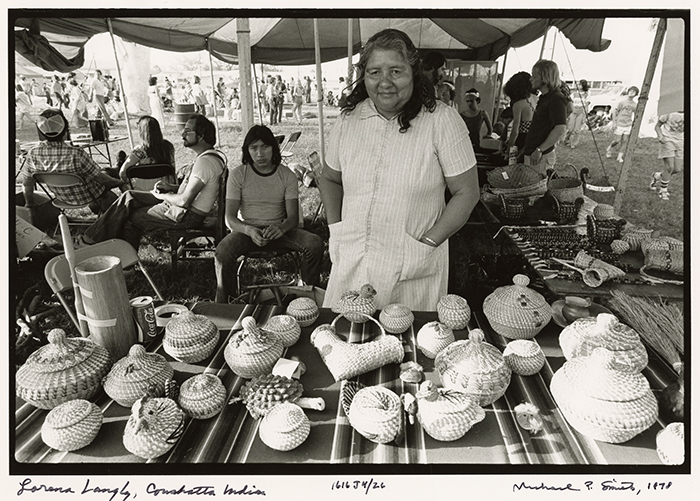

Lorena Langley stands by her craft table at the 1978 New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival in this photograph by Michael P. Smith. Langley and her family made traditional Coushatta Indian–style pine-needle basketry.

The Langley and Abbey families are noted basket makers from the Coushatta Indian Tribe in Allen Parish in southwest Louisiana. Utilizing Louisiana native longleaf pine needles, they craft tightly bound, classic forms and whimsical animal shapes in the tradition of their ancestors. The earliest baskets were used as containers for carrying goods, currency for acquiring food and other necessities, and, in dire economic periods, the sole means of generating income. The skills of the tribe’s contemporary weavers have elevated this centuries-old utilitarian craft to a highly valued art form showcased in private and museum collections nationwide.

A matrilineal society, the Coushatta Tribe of Louisiana arrived in the southwest part of the state in the 1880s and received federal recognition as a sovereign nation in 1973 along with designated reservation lands two years later. Today most of the thousand members live north of the small town of Elton, the seat of the tribal government, with others found several miles west in Kinder, Louisiana. Organized into seven matriarchal clans, the Coushatta are governed by a five-person council and are notable for their ongoing efforts to preserve tribal customs in the realms of material culture, folklore, linguistics, and foodways.

Baskets have long been central to the Coushatta’s way of life and were traditionally made of river cane, wiregrass, and split white oak. During the mid-twentieth century, however, weavers began using Louisiana long-leaf pine from the Pinus palustris tree as other materials became increasingly scarce. Baskets are made by coiling small bundles of the needles with strands of raffia pulled through a sewing needle. Often decorated with small pinecones or raffia floral designs, creations range from round, often bulbous forms with tightly fitting lids to playful animal shapes known as effigies.

Bearing distinguished Coushatta lineages, the Langley and Abbey families trace their shared ancestry to Ency Abbey Abbott (1896-1956), the tribe’s last recognized medicine woman and a savvy landowner who negotiated mineral leases with local oil and gas companies. Ency had seven children from two different marriages: one to Dennis Abbey, from 1915 until his untimely death three years later, and another to Lounie Abbot, from 1922 to his death in 1942. Like generations of Coushatta women before her, Ency instilled in her offspring a deep respect for their heritage and a desire to perpetuate tribal customs.

Ency’s last-born child, Edna Lorena Abbott Langley (1933-2009), was one such cultural ambassador and tradition bearer. In addition to weaving exquisite pine-needle baskets, she was one of the last known Coushatta potters, creating vessels that had once been made to store traditional herbal medicines. She was also fluent in Koasati, a Muskogean language that survives in a relatively pure form among its few remaining speakers. Langley’s crafts received recognition at national arts fairs and are held in prominent collections across the South. In 1993, Langley was inducted into the Louisiana Folklife Center’s Hall of Master Folk Artists. Today, Langley’s children, Rosalene Langley Medford and Ronald Langley, continue their mother’s artistic legacy by demonstrating pine-needle basket weaving at area fairs and festivals.

Lorena’s half-brother Bel Abbey (1916-1992), and his wife Nora Williams Abbey (1920-1984), also inherited an appreciation of their tribal heritage, shared, in turn, with daughters Joyce Abbey Poncho, Myrna Abbey Wilson, and Marjorie Abbey Battise. The sisters are skilled pine-needle basket makers and, while most weavers demonstrate individual techniques, Battise’s left-handedness results in a distinct “backwards” stitch. She is also a historian of Coushatta foodways and demonstrates traditional tribal foods such as fry bread and corn soup at folk festivals. Wilson has helped to preserve the tribe’s cultural heritage through the perpetuation of classic Coushatta narratives learned from her father. Poncho not only creates baskets from pinestraw, but also maintains the split cane basketry tradition. Bel Abbey, a master storyteller, helped to create a Koasati dictionary and a translation of the Bible in the tribe’s ancestral language. Wilson and Battise, along with their father, were inducted into the Louisiana Hall of Master Folk Artists in 1982. Poncho resides with her husband Robert in Livingston, Texas, in the Alabama-Coushatta community.

With the opening of the Coushatta Casino Resort and in-house gift shop in the mid-1990s, weavers have experienced an increased demand for their baskets. They face, however, a shortage of Louisiana long-leaf pine needles due to deforestation, which has forced them to utilize the faster-growing slash pine (Pinus elliottii) or import their preferred material from other parts of the state. Coushatta baskets are in the permanent collections of the National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C., the Louisiana State Museum, the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnography at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and many esteemed private collections across the country.