Domestic Slave Trade

The domestic slave trade, central to the economic growth of Louisiana, destroyed enslaved people’s families, wreaked havoc in their communities, and killed many, despite their attempts to resist.

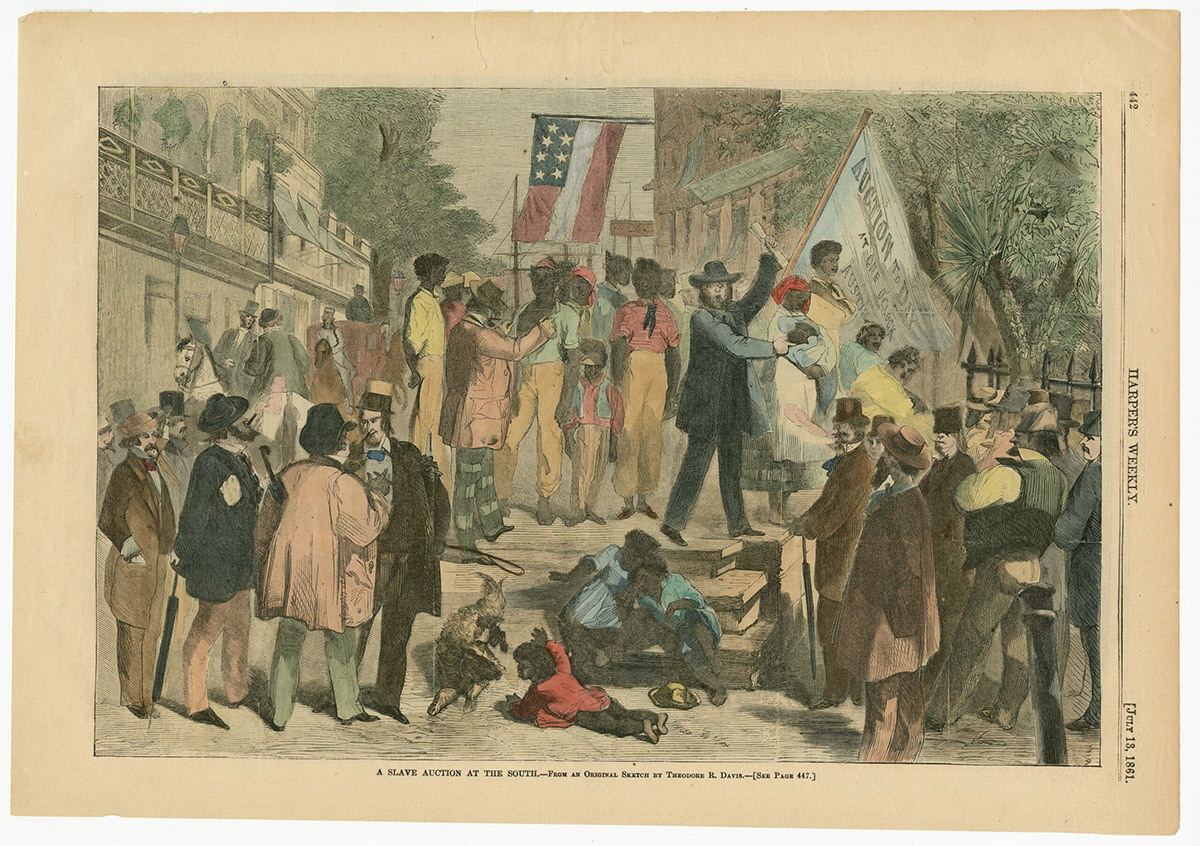

The Historic New Orleans Collection

"A Slave Auction At The South," 1861.

The domestic slave trade refers to buying and selling enslaved people within the boundaries of the United States and its territories. It usually included forced migration, either across state lines or within individual states. Though the domestic slave trade and the Atlantic slave trade were similar, the domestic slave trade involved enslaved people who were born in, or already lived in, the country. Historians estimate that slave traders, people who worked as merchants in human beings, bought and sold two million enslaved people through the domestic slave trade. Slave traders or enslavers forced one million of these people to migrate to other states. The domestic slave trade was central to the economic growth of many southern states, especially Louisiana. The practice destroyed enslaved people’s families, wreaked havoc in their communities, and killed many. Abolitionists turned the trade into a powerful symbol of slavery and based many of their public attacks against enslavement on the moral evil of buying and selling human beings.

A slave trade existed in colonial Louisiana during the eighteenth century, but only in the nineteenth century did the state become central to the domestic slave trade. A ban against the Atlantic slave trade took effect in the United States in 1808, meaning that slaveholders could no longer legally import enslaved people from overseas. As a result, prices for enslaved people rose, especially in new southwestern territories and states of the United States, like Louisiana, which became a territory as part of the Louisiana Purchase in 1803 and joined the Union in 1812. Soon, slave traders learned that they could make profits by buying enslaved people in states with large enslaved populations, like Virginia, and forcing them to states like Louisiana, where enslavers were establishing new cotton and sugar plantations. Because the bulk of the domestic slave trade occurred after the closing of the Atlantic slave trade, the domestic slave trade is sometimes referred to as the “Second Middle Passage.”

New Orleans and the Domestic Slave Trade

Because of its location on the Mississippi River near the Gulf of Mexico, New Orleans became a central hub of the slave trade in the lower South. Slave traders forced enslaved people aboard ships in eastern river cities and Atlantic Ocean ports and shipped them to New Orleans. Baltimore, Maryland; Washington, DC; Norfolk, Alexandria and Richmond, Virginia; and Charleston, South Carolina, were common origins of slave ships. Solomon Northup, a free Black man, was shipped by ocean and sold into slavery in New Orleans after being kidnapped in Washington, DC. Others collected enslaved people into chained groups, called coffles, and forced them to walk from the upper South to the lower South. Finally, slave traders were also active in places like Kentucky and Tennessee. They forced enslaved people aboard Mississippi River flatboats and steamboats and shipped them down the river to New Orleans, stopping to sell people in cities and towns along the way. Early in the nineteenth century, slave traders operated small businesses and utilized ships already filled with other goods bound for Louisiana; John McDonogh operated in this manner. By the 1830s however, slave traders like Isaac Franklin (owner of Angola Plantation) and John Armfield learned that they could make even more money by owning all the infrastructure that made their business work, including slave holding pens and the ships that transported people. Because shipments were valuable and risky, slave traders frequently insured their human cargos to stave against potential losses.

The market for enslaved people in New Orleans tracked the price of the major staple crops of nineteenth-century Louisiana: cotton and sugar. When prices for those commodities rose, plantation owners planted more and traveled to the market to purchase more enslaved laborers. Likewise, when crop prices declined, or when the economy crashed, enslavers avoided the market or sold people to satisfy creditors. Because enslaved people were worth so much money, mortgages—loans secured by property—made many sales possible. Banks, including the Bank of the United States and the New Orleans-headquartered Citizen’s Bank of Louisiana, backed many of these mortgages. High mortality rates in Louisiana’s sugar parishes, caused by overwork and rampant disease, meant there was steady demand for enslaved laborers at the New Orleans market.

Enslaved people also left New Orleans via the slave trade. Slave traders sent some north to Natchez, Mississippi, and other Mississippi River commercial hubs. The majority exported out of state probably left New Orleans for other ports in the Gulf of Mexico. In the early nineteenth century, enslavers shipped enslaved people to nearby ports in Mississippi and Alabama. When plantation agriculture accelerated in Texas in the two decades before the American Civil War, slave traders in New Orleans found growing markets in Galveston and other towns on the Texas coast. Charles Morgan, the operator of a steamship line between New Orleans and Galveston, made much of this trade possible. One descendant of an enslaved man in Texas said that his father’s enslaver made “trips to New Orleans to buy slaves and brung ‘em back and sol’ ‘em to de farmers.”

The Domestic Slave Trade in Louisiana Towns

New Orleans was a major regional hub, but other towns in Louisiana and along the Mississippi River also developed slave markets. The market at Natchez, Mississippi, was perhaps the second-most notorious in the lower South. It supplied cotton plantations in Mississippi and those across the river in Louisiana with enslaved people. On the Mississippi River, markets also existed in Baton Rouge and Donaldsonville, as well as in Vicksburg, Mississippi. Usually parish seats, where the government and legal bodies convened, became local hubs for the slave trade. Slave traders utilized interior navigable waterways, like bayous, that connected many towns. Enslavers from nearby plantations traveled to parish seats to purchase enslaved women, men, and children from slave traders there. They also purchased enslaved people from parish sheriffs, who acquired them through legal processes meant to satisfy creditors and by capturing and imprisoning suspected runaways. Thus, courthouses in rural towns were often sites of slave trading. One descendant of an enslaved person in St. Mary Parish remembered “a dock, right where the courthouse is now, that’s where they used to sell them, in Franklin,” the parish seat.

Enslaved People’s Resistance and Abolition

Enslaved people resisted the slave trade as best they could. They fled at the threat of sale, attacked slave traders, and attempted to return home. During a court hearing, a witness stated that white men employed by slave traders to accompany coffles to New Orleans worked jobs “considered by some as dangerous, and many persons would be unwilling to engage in it.” The chains that bound enslaved people and the guns that slave traders carried gestured to the threat of resistance. The 1841 shipboard revolt on the Creole is one of the most famous instances of resistance to the domestic slave trade. Enslaved people from Virginia took over a ship bound for New Orleans and navigated it to the British Caribbean colony of The Bahamas.

Abolitionists, white and Black people who wanted to end slavery, often brought up the slave trade as a clear example of slavery’s evil. According to historian Walter Johnson, enslaved people crafted a critique of slavery that focused on the slave trade’s “chattel principle,” the idea that people were worth a price. When self-emancipated people fled north through the Underground Railroad, they brought this critique with them and influenced the abolitionist movement. As interstate commerce, the trade was also potentially vulnerable to prohibition by Congress. Because New Orleans was a central hub of the domestic slave trade, its slave markets became a symbol for the trade. The horrors of Louisiana’s slave trade are important elements in abolitionist Harriet Beecher Stowe’s 1852 novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin. It was, perhaps apocryphally, a trip to New Orleans and its slave market that demonstrated to a young Abraham Lincoln the repugnance of slavery.

Conclusion

The domestic slave trade made possible the westward expansion of slavery in the United States and was crucial to the country’s economy. It wed the upper and lower South, slave-exporting and slave-importing states, together in an economy based on enslavement. In Louisiana, it enabled the expansion and intensification of agricultural production, especially in crops like cotton and sugar, by supplying enslavers with the enslaved people who performed the labor. Due to New Orleans’s location and proximity to cotton and sugar regions, the city became a major slave trading port. The domestic slave trade also wrought horrendous consequences in the lives and communities of enslaved people, despite their attempts to resist. It tore apart their families, decimated their communities, and caused incalculable physical, emotional, and spiritual trauma. Survivors understood the slave trade for what it was, and they influenced northern abolitionists with their critiques of the trade that implicated slavery as whole. The domestic slave trade continued to the end of the American Civil War, but the end of slavery also meant the end of the slave trade.