Slave Insurrections in Louisiana

Slavery existed in Louisiana from its earliest origins as a French colony through the Confederacy's defeat in the Civil War. Slave insurrections, however, were unusual events.

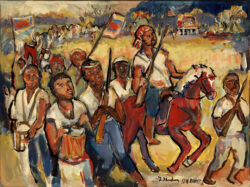

The Historic New Orleans Collection.

1811 Revolt by Lorraine P. Gendron, 2000.

Slavery persisted in Louisiana from its earliest origins as a French colony until the Confederacy’s defeat in the Civil War (1861–1865). Despite one major uprising that has been called the largest slave rebellion in US history—the Slave Insurrection of 1811—organized slave revolts were the exception rather than the rule in the state. Resistance to enslavement in various forms was natural and constant. For that resistance to take the shape of an organized conspiracy was rare; for those conspiracies to develop into full-fledged insurrections—as in the St. Domingue Revolution (1791–1804)—was rarer still. Given the enormous disparity in armed forces and social power between slaves and their white masters, this is hardly surprising. To engage in open rebellion was tantamount to suicide; it is remarkable not that there were so few slave rebellions, but that any occurred at all.

The French Period (1682–1762): Indian-Slave Alliance

Although the Natchez massacre of 1729 was primarily a Native American rebellion, it also involved elements of slave resistance. Both Native Americans and Africans were commonly enslaved in early French Louisiana, and in this episode many slaves took the side of Indian attackers against the French. On November 28, 1729, hunters from the Natchez Tribe asked French settler families at Fort Rosalie to borrow their guns for a hunting trip in exchange for food. After the guns were handed over, the Natchez began to shoot the French, eventually slaughtering 237 men, women, and children—with the collusion of some slaves. Several blacks escaped, but most were taken prisoner. When the French counterattacked two months later, most of the African prisoners fought alongside the Natchez rather then yield to their former enslavers.

For two years after the Natchez revolt, French anxieties revolved as much around rebellious slaves as hostile Indians; rumors swept the colony of a combined African-Indian plot to take over the colony and massacre the whites. Governor Etienne de Périer felt that a potential “union between the Indian nations and the black slaves” would lead to the “total loss” of Louisiana. A cadre of particularly militant Bambara slaves, led by a trusted slave lieutenant of Antoine-Simon Le Page du Pratz, allegedly planned to kill all the whites in the colony and enslave all the non-Bambaran blacks. Numerous conspirators confessed (albeit under torture); one woman was hanged, and eight men broken on the wheel. Six months later, another abortive plot was to have surprised the French at the 1731 Christmas midnight mass.

The goal of these slave uprisings was apparently not to end slavery as a social system but to violently win control of a slave-based colony. The rebellious slaves of the 1720s and their Native American allies did not succeed in killing off the French or taking over Louisiana. They did, however, contribute to a degree of instability that was a factor in the eventual departure of the French Company of the Indies from Louisiana.

The Spanish Period (1763–1800): Ideological Upheaval

The early years of Spanish rule saw a liberalization of regulations on slavery and an absence of organized slave resistance. By the 1780s, there was an endemic problem of fugitive slaves living in organized groups and occasionally raiding plantations. Governor Esteban Miró cracked down on this marronage starting in 1783; in June 1784, the notorious maroon leader Juan San Malo was hanged alongside three of his lieutenants.

It was not until 1795 that another large-scale insurrection conspiracy took place in Louisiana. In the intervening years, the ideological contours of the Atlantic world had been remapped by the French Revolution (1789–1799) and the related St. Domingue Revolution (1791–1804). Rumors of revolution and egalitarian ideas traveled by word of mouth throughout the world of the enslaved, in what one scholar has called a “common wind.”They reached from the capitals of Europe all the way to remote colonial outposts—even to Pointe Coupée (the present-day location of New Roads), 125 miles upriver from New Orleans.

The Pointe Coupée conspiracy began in April 1795 among the slaves of Julien Poydras, one of the wealthiest planters in Louisiana and a future American political leader. Men outnumbered women by more than ten to one among the Poydras slaves, almost all of whom were Africans. They knew about the successful overthrow of the slave system in St. Domingue and of France’s subsequent abolition of slavery throughout her colonies. They may also have heard rumors of an invasion of Louisiana from the east, by Jacobin-influenced Francophile American settlers led by George Rogers Clark. Led by Poydras’ overseer, Antoine Sarrasin, the rebels planned to set fire to several buildings and then use the confusion to seize weapons and kill their masters, along with uncooperative Creole slaves. They coordinated with slaves from neighboring estates, who were expected to strike simultaneously. They also included sympathetic whites in the plot, including a schoolteacher named Joseph Bouyavel, who had read the Declaration of the Rights of Man aloud to slaves on nearby plantations.

Betrayed by informants among the Tunica Tribe, the plot was uncovered and trials took place in May 1795. Many accused conspirators swore that they took part in the plot only because of violent intimidation by its ringleaders. Ultimately, fifty-seven slaves and three whites were convicted of participation, and twenty-three of those convicted were executed, with their severed heads nailed to poles along the Mississippi River’s banks in keeping with an old tradition of exemplary punishment.

The American Period (1803–1865): Rise of the Sugar Country

In the same year as the Pointe Coupée conspiracy, sugar cultivation was introduced to southern Louisiana. By the time the United States took over the colony eight years later, many of the largest plantations had converted to sugar production. The lure of high profits spurred the import of yet another new cohort of African slaves, until the international trade was closed in 1808. Sugar production was concentrated in the New Orleans region and along a stretch of land upriver known as the German Coast.

The winter of 1810 saw a series of regional upheavals: in Mexico, the Catholic priest Miguel Hidalgo sought to end colonial rule and abolish slavery, while in nearby West Florida, a group of white settlers overthrew the Spanish regime and proclaimed an independent state. Either of these developments may have inspired the slaves on the estate of Manuel Andry—including Andry’s overseer, a rented Creole slave named Charles Deslondes. Deslondes played a central role in the Slave Insurrection of 1811 (also known as the German Coast insurrection), an uprising that has been called the largest-scale slave revolt in US history—with as many as five hundred slaves participating. Andry’s slaves surrounded his house in a cold rain on the night of January 8, then broke in and killed Andry’s son Gilbert. Andry himself escaped across the Mississippi and began to round up a posse of nearby planters. Meanwhile, the rebels, led by Deslondes, proceeded south, torching and looting adjacent plantations and adding recruits to their ranks.

By the next day, a stream of panicked white refugees was entering New Orleans with breathless accounts of the uprising. General Wade Hampton, himself one of the wealthiest slaveholders of South Carolina, was in New Orleans with several companies of federal troops, drawn there by the unrest caused by the West Florida revolt. His men joined with volunteers—many of whom were sailors on Commodore John Shaw’s brig, the Syren—to form a force of about one hundred men marching north to confront the rebellious slaves. Governor William C. C. Claiborne also called out the volunteer battalion of free men of color to keep order in the city.

The number of rebels, meanwhile, had increased to several hundred men (eyewitness accounts vary widely, ranging from 150 to 500), who now carried weapons and wore uniforms. Drummers beat time as the slave army continued to move downriver, chanting “on to Orleans!” By the evening of January 9, they had killed one more planter and made a camp at Jacque Fortier’s plantation, just twenty-five miles above New Orleans. Hampton’s federal force drew near at dawn on January 10 but spooked the rebels, who were able to retreat safely back upriver. In the end it was the posse led by Andry and another planter, Charles Perret, that engaged Deslondes’ rebels. It was a one-sided battle: in Andry’s words, “we made considerable slaughter” (un grand carnage). About fifty slaves died in the attack, including Deslondes. The rest dispersed into the cypress swamp, where Native Americans helped track them over the next few days—not a single white man was killed.

A tribunal at the Destréhan plantation sentenced the twenty-one surviving rebels to death by firing squad. As at Point Coupée in 1795, the severed heads of those executed were mounted on poles along the levee and remained there for months afterward. Hampton was impressed by the savagery of the Creole planter posse, writing “they are equal to the protection of their property,” and going on to invest heavily in Louisiana sugar land. Slavery, of course, expanded dramatically in the lower Mississippi Valley in the next half-century, abetted by a strong international demand for sugar and cotton and a thriving domestic slave trade. But there was never another significant slave insurrection in Louisiana until slavery’s demise in the Civil War (1861–1865).

Common Threads

Slave insurrections were rare, exceptional occurrences. Each had unique characteristics and contingent circumstances, but there are also clearly observable common threads. Insurrections tended to be organized and led by trusted elite slaves, especially overseers. They occurred in places where high percentages of the slave population were male, young, and recently arrived from Africa. They followed, by several years, peaks in the highly uneven volume of slave importation—peaks that occurred in the early 1720s, in the late 1780s, and in the four years from 1804 to 1808. And they often occurred in times and places where strong political and social tensions were destabilizing the wider community.

If rebellions were rare, white panics over alleged slave conspiracies were common. The records of early Louisiana are filled with documents alleging the existence of a planned insurrection or “massacre of the whites”—especially after the eruption of the St. Domingue Revolution in 1791. In 1804, for example, New Orleans residents sent Governor Clairborne a petition alleging a plot by all the slaves in the city and insisting the governor investigate and punish the guilty slaves “without any compassion.” Claiborne saw no evidence of a serious threat and this panic passed, as did many others. On the other hand, at particularly tense times, these panics could lead to harsh retributive violence—as happened at Second Creek, Mississippi, in the early weeks of the Civil War, when a rumored insurrection led to the execution of at least twenty-seven slaves.

It is worth emphasizing that the actual insurrections that came to fruition in Louisiana were small in scale and stood little realistic chance of success. They were not, as historian Peter Kolchin points out, on nearly the same scale as the Russian peasant revolts that involved tens of thousands of serfs in large-scale battle with conventional military forces. Nor were they comparable in scale or scope to the insurrections that devastated plantation societies in St. Domingue, Jamaica, or South America. Though Louisiana’s slave system is often considered similar to those of the Caribbean and Latin America, the pattern of slave rebellions tells a different story. On this one issue, Louisiana’s history resembles that of other parts of the United States, into which it was eventually incorporated.

The relative dearth of slave rebellions, however, should not be taken as evidence that slaves were in any way content with their lot. To downplay episodes of resistance or emphasize their rarity risks unintentionally reinforcing the racist picture of the docile, contented slave. In fact the definition of “resistance” has been hotly contested. Most scholars agree that running away—which was common in Louisiana, where “maroon” communities of escaped slaves gathered in cypress swamps—was a form of resistance, as were such individual acts such as poisoning, stealing, and sabotage. More controversially, other scholars have characterized “shirking,” “foot-dragging,” self-mutilation to avoid work or sale, and even suicide under the rubric of resistance.

Individual actions constituted safer ways for slaves to resist their captivity than open violent insurrection. Also, in early Louisiana, especially during the Spanish colonial period, slaves had opportunities for manumission, either from a generous individual owner in exchange for loyalty or through self-purchase. To be sure, the large majority of slaves were never freed, but the existence of these possibilities nonetheless served to divert energies that might otherwise have been channeled into rebellion.