Florville Foy

Florville Foy, a free man of color, was a marble cutter, sculptor, and proprietor of one of the most successful marble yards in nineteenth-century New Orleans.

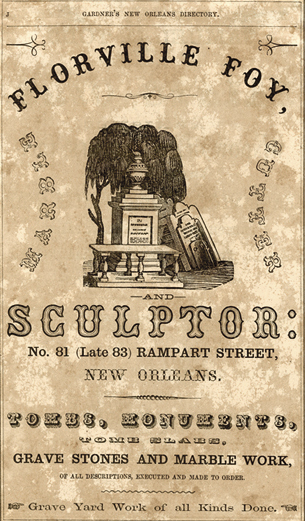

Courtesy of The Historic New Orleans Collection

Advertisement for Florville Foy, Sculptor. Gardner's New Orleans Directory

Florville Foy, a free man of color, was a marble cutter, sculptor, and proprietor of one of the most successful marble yards in nineteenth-century New Orleans. His signed tombs, vaults, and memorial objects may be seen in the oldest “cities of the dead:” St. Louis Cemetery I, St. Louis Cemetery II, and St. Louis Cemetery III, as well as in Catholic cemeteries along the Gulf Coast. Foy’s career success came at a time when free blacks in other parts of the South faced increasing animosity. Though certainly not free of racism, New Orleans provided a more hospitable working environment for Foy and other free men of color—including Julien Hudson, Jules Lion, and Louis Lucien Pessou—who made their living as artists.

Born June 29, 1819, the son of Prosper Foy, a French immigrant and veteran of the Napoleonic Wars, and Heloise “Zelie” Aubry, a free woman of color and native New Orleanian, Florville Foy was the only son of the couple’s five surviving children. He was educated by private tutors and by his father, a writer, bon vivant, sculptor, marble cutter, and, in later life, a planter. In 1836 the younger Foy first advertised his services as a marble cutter; among his clients were the church wardens of St. Louis Cathedral, who hired him to build wall vaults. Besides creating his own designs, he was employed to build a series of remarkable tombs, many with elaborately carved decorative elements, from the designs of French immigrant architect J. N. B. DePouilly. As his business grew, he hired other artisans, eventually employing a staff of nine.

In 1850 Louisa Whittaker, a white woman from Mississippi, came to live with him. Shortly afterward, he purchased a three-story red-brick building with adjoining marble yard on North Rampart Street; the shop was on the ground floor, and the couple lived on the upper two floors. Next door was St. Anthony’s Mortuary Chapel, where the city’s funerals took place; the business was convenient to both St. Louis cemeteries and to the Carondelet Canal, via which Foy received loads of marble and shipped signed tombs to Pensacola and Biloxi.

Foy became quite wealthy, and his work was often praised by local newspapers. In 1885 he and Whittaker married during the twenty-year period when interracial marriage was legal in Louisiana. Although eventually outpaced by well-capitalized competitors, Foy continued in business until his death on March 16, 1903. In addition to his work in the city’s historic cemeteries, his large sculpture from the demolished Girod Street Cemetery, Child with Drum, is at the Louisiana State Museum. Foy is interred in a large, simple tomb in St. Louis Cemetery III.