Frances Benjamin Johnston

Frances Benjamin Johnston's seven-decade career as a photographer began in Washington, D.C. during the presidency of Benjamin Harrison, and concluded in New Orleans, months before Dwight Eisenhower's election to the same office.

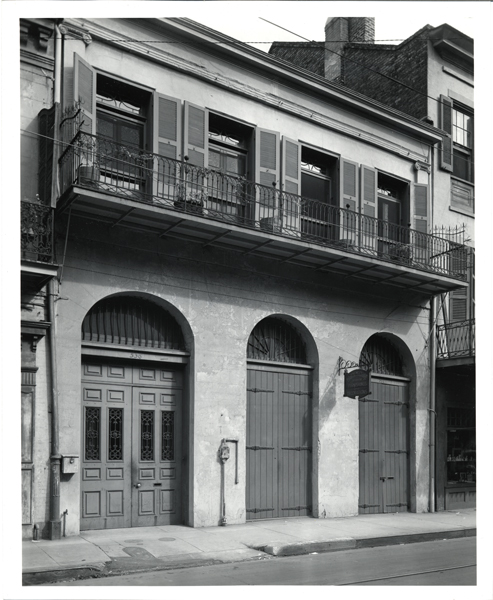

Courtesy of Louisiana State Museum

534 - 536 Royal Street. Johnston, Frances Benjamin, (Photographer)

Frances Benjamin Johnston’s seven-decade career as a photographer began in Washington, D.C., during the presidency of Benjamin Harrison, and concluded in New Orleans, months before Dwight Eisenhower’s election to that office. One of the first American women to achieve prominence as a photographer, Johnston’s career was marked by two distinct phases: one that included photojournalism and a successful portrait practice in the nation’s capital catering to the politically powerful and connected; and another that was principally centered on the grand architecture and gardens of the antebellum South.

Johnston was born in Grafton, West Virginia, on January 15, 1864. Her education in Maryland as a young woman included art instruction, and beginning in 1883, she studied painting for two years at the Académie Julian in Paris, France. Upon returning to Washington she began studying photography and opened a studio about 1890. In 1901, Johnston became the first person to hold the title of official White House photographer, designated by President Theodore Roosevelt.

Johnston’s approach to photography was straightforward, exploiting the clarity of what she termed “the more accurate medium” compared with other forms of illustration. Critic Lincoln Kirstein referred to her images from the famed Hampton Institute Album (1899–1900), a collection of images from the African-American trade school, as “inexhaustibly revealing.” The same images prompted curator John Szarkowski to characterize her as a “drill sergeant among photographers” for the formal rigor and compositional structure of the images. This straightforward outlook was one that transferred well to photographing buildings and their settings.

By 1910, Johnston’s interests began to turn toward photographing architecture and gardens, and remained principally so for the rest of her life. In 1927, a privately funded project permitted Johnston to photograph historic structures in Fredericksburg, Virginia. A few years later, enlisting support from the Library of Congress, where she deposited those pictures, she was given a grant by the Carnegie Foundation and traveled through nine southern states (Virginia, Maryland, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Florida, Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana) to photograph antebellum architecture. Of the more than 7,200 negatives she produced for the survey, some 40 percent were made in Virginia, the first state her survey covered. A rigorous and systematic approach to photographing historic structures gives this survey a consistent viewpoint and methodology. Johnston’s photographs included significant architectural details—both interior and exterior—and represented many examples of vernacular structures along with grand ones. Her thorough approach to photographing buildings set the groundwork for a similar style used by the federally funded Historic American Buildings Survey, begun in 1933.

Many of Johnston’s photographs (more than 400) made in Louisiana—plantation structures, French Quarter courtyards, and homes in New Orleans’ Garden District—date from the late 1930s. In 1940, she moved to New Orleans, where she became a resident of the French Quarter, and in 1941, an exhibition of her photographs was mounted by the Arts and Crafts Club of New Orleans, an artists’ collective also in the Vieux Carré.

In recognition of her efforts to document and recognize the country’s architectural heritage, she was named an honorary member of the American Institute of Architects in 1945, at the association’s meeting held that year in New Orleans. Collections of photographs from Virginia, North Carolina, and South Carolina, were published during her lifetime. A volume on the architecture of Georgia was published posthumously. At the time of her death, a book on the buildings of the lower Mississippi Valley, principally in Louisiana, was in preparation, though never published.

Johnson died in New Orleans on March 16, 1952. Johnston’s Her negatives and a large number of prints are held at the Library of Congress. Museums throughout the country—including the Louisiana State Museum and The Historic New Orleans Collection—hold examples of her prints in their collections.