Freeman & Harris Café

Freeman & Harris Café was a Black-owned restaurant that served as a pillar of Black social, cultural, and political life in Shreveport.

Northwest Louisiana Archives at LSU Shreveport

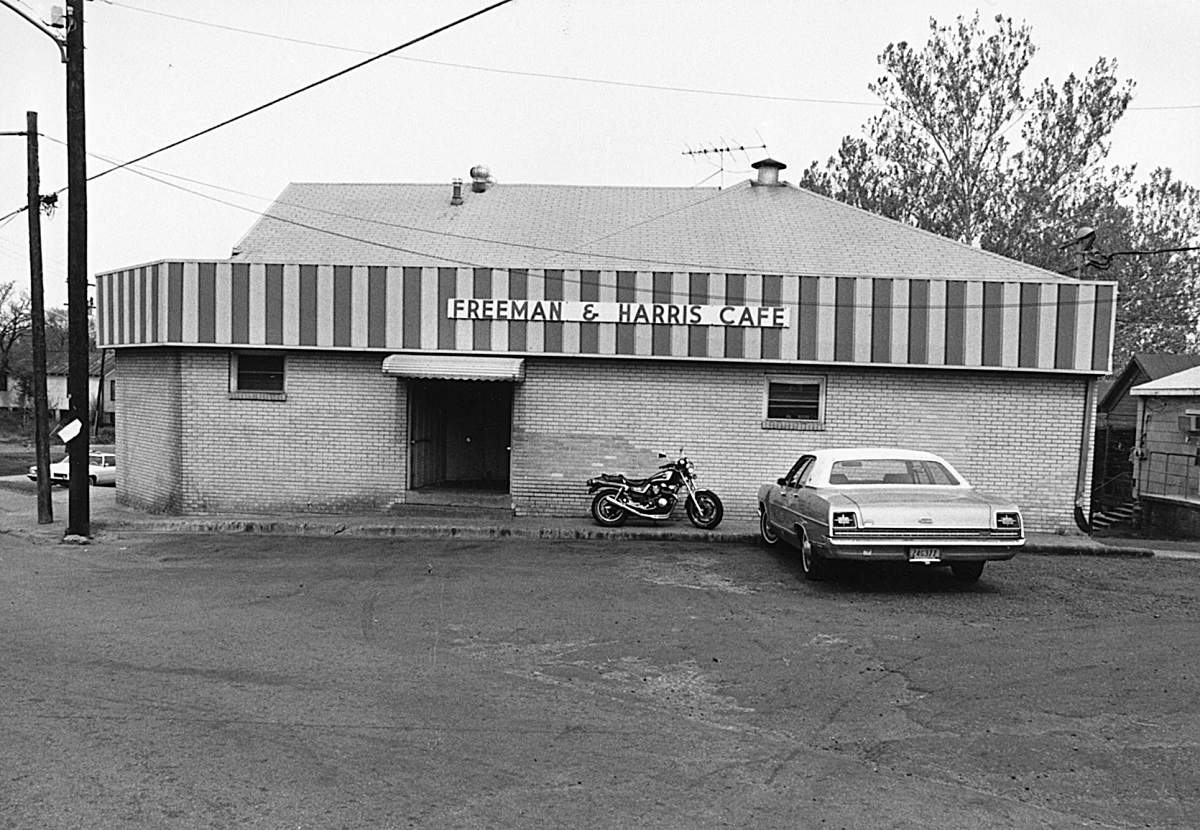

Freeman & Harris Café, 1984. Neil Johnson, photographer.

Freeman & Harris Café was a restaurant owned and operated by first cousins Van B. Freeman Jr. and Jack Harris, first at 1017 Texas Avenue and later at 317 Western Avenue in Shreveport. Originally located in the heart of a Black-owned business district known as “The Avenue” or “Mugginsville,” the restaurant began as little more than a food stall and grew into a pillar of Black social, cultural, and political life in Shreveport. Members of the Freeman and Harris families operated the restaurant for more than seventy years after its opening as Freeman Café in the early twenties (both 1921 and 1923 have been reported) until its permanent closure in 1994.

Van B. Freeman Jr. moved to Shreveport from the Campti area of Natchitoches Parish sometime between 1910 and 1920. His move may have been prompted by a downturn in the Freeman family’s economic situation, which resulted in the 1924 public auction of his father’s 149-acre Cane River farm. Census data shows that Freeman was living in Shreveport and working as a cook at the Washington-Youree Hotel by 1920. He made several attempts to operate his own restaurant in the twenties, including businesses named Penny Rock Café, Dew Drop Inn Café, and Freeman Café. In 1928 he was joined in his restaurant enterprise by first cousin Jack Harris, also of Campti, and by 1930 the name of the business was changed to Freeman & Harris Café. The restaurant temporarily closed twice during the Great Depression, in 1932 and 1935, before reopening in 1936 in a much larger space at 317 Western Avenue. At the Western Avenue address, Freeman & Harris Café gained notoriety for dishes like fried trout, shrimp fried rice, and “chicken in a box.” It also became known as a popular place for Shreveport’s growing Black middle class to socialize, talk politics, and see and be seen. Freeman and Harris both died in 1947, leaving their popular restaurant in the hands of three trusted team members: Pete Harris, Arthur “Scrap” Chapman, and Wilmer “Tody” Wallette.

Pete Harris and Stuffed Shrimp

During its heyday in the 1950s and 1960s, Freeman & Harris Café was managed by Pete Harris, the Xavier University-educated nephew of Jack Harris. Under his leadership in the late fifties, the restaurant developed what would become its signature recipes for cornbread crumb-battered, deep-fried stuffed shrimp and a spicy, remoulade-like dipping sauce. Freeman & Harris Café promoted its dipping sauce as tartar sauce even though it bore little resemblance to the classic French sauce of the same name. Freeman & Harris Café’s stuffed shrimp and tartar sauce were such huge hits with customers that they were adapted or copied outright by several competing restaurants. Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, the proliferation of restaurants specializing in stuffed shrimp—many of which were owned by former employees of Freeman & Harris Café—helped to establish the dish as a citywide phenomenon. Pete Harris managed the restaurant for thirty-five of its most successful years. He became a part-owner of the business in 1965. He died in 1992 and was posthumously inducted into the Louisiana Restaurant Association Hall of Fame in 1993; he was the first Black man ever inducted.

“A Political Fortress”

Meals at Freeman & Harris Café were often served with a side of politics. Late Shreveport historian Eric J. Brock wrote that Freeman & Harris Café began seating white customers and Black customers together in the same dining room in the late 1950s, making it the city’s first integrated restaurant. Community organizers and activists hosted meetings and forums in the restaurant’s basement during the civil rights era. Martin Luther King Jr. dined and held meetings at Freeman & Harris Café during three visits to Shreveport between 1958 and 1962. Following the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which greatly increased the number of Black registered voters, the restaurant began regularly hosting campaign stops and forums featuring local, state, and national candidates for public office. In a 1981 local newspaper article about the restaurant’s long-running involvement in politics, the Shreveport Times called Freeman & Harris Café “a political fortress of a restaurant located in the heart of [B]lack Shreveport.”

Freeman & Harris Café closed permanently in 1994 because of a long-simmering financial dispute between descendants of the restaurant’s founders. Its best-known dishes, including stuffed shrimp (as well as memorabilia, menus, and photos from the storied restaurant’s past), can still be enjoyed at several Shreveport eateries that carry on the traditions of Freeman & Harris Café. Surviving restaurants that still serve Freeman & Harris-style stuffed shrimp and tartar sauce include Eddie’s Restaurant, C&C Café, and Orlandeaux’s Cross Lake Café.