Goldband Records

Goldband Records was a nationally recognized music label with a unique catalog of music spanning several genres, including western swing, “hillbilly” string band, Cajun, zydeco, rhythm and blues, and rockabilly.

The Louis Round Wilson Special Collections Library at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

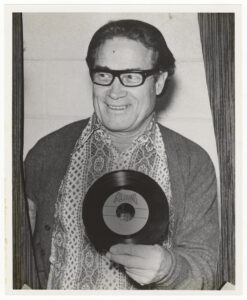

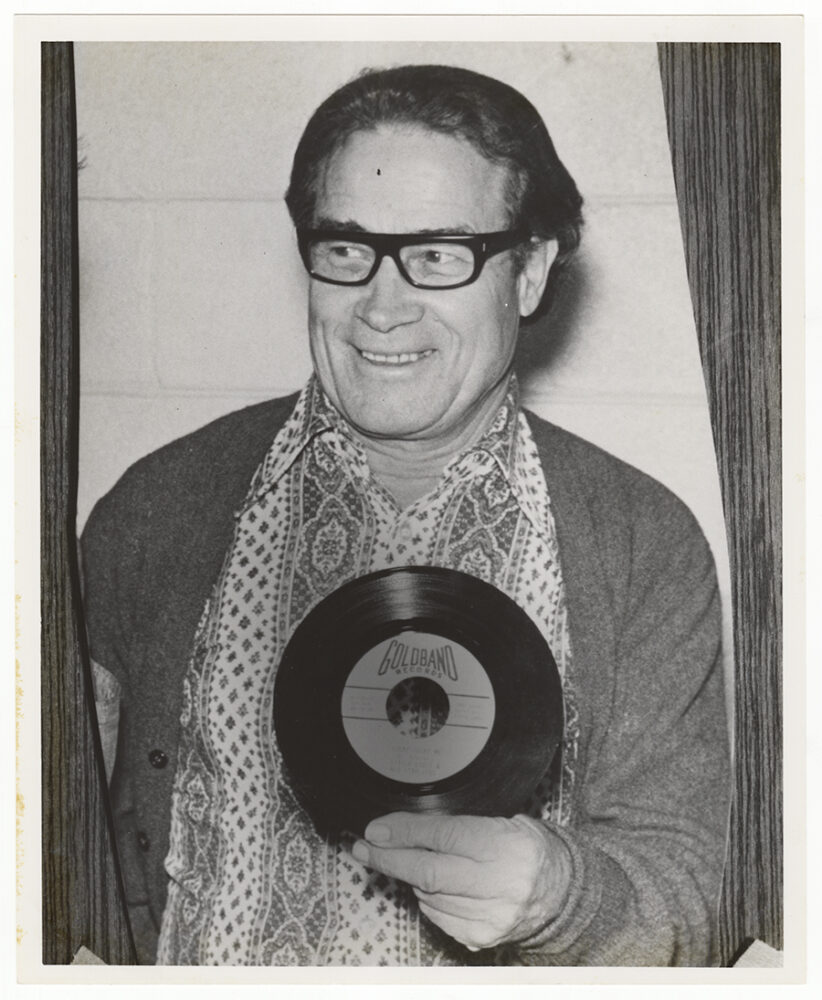

Eddie Shuler holding a Goldband album, undated.

Goldband Records was the brainchild of musician, disc jockey, and record producer Edward Wayne Shuler Sr., better known as Eddie Shuler. Over sixty years, Shuler’s recording business went from a vanity label for his Western swing outfit to a pioneering recording outlet for regional and national musicians. Located in Lake Charles, Goldband Records straddled the boundary separating French-speaking Cajun and Creole culture from the more predominate Anglicized East Texas culture. In the end, Goldband Records became regionally and nationally recognized, with a unique catalog of music spanning several genres, including western swing, “hillbilly” string band, Cajun, zydeco, rhythm and blues (R&B), and rockabilly.

The Early Years

Shuler was born on March 27, 1913, in Wrightsboro, Texas. He moved to Lake Charles in 1941 in search of construction work when a western string band known as the Hackberry Ramblers invited the burgeoning guitarist to join them. By the end of World War II, Shuler tried his luck opening a music store and forming his own group called the Reveliers. With limited exposure he knew he needed to find a way to market his band and decided to create his own record label, Goldband, in 1945. “I wanted a record that would attract attention,” he told music journalist Andrew Brown in 2001. “Goldband, that’s like the ring on your finger, and they can relate to that. We’re gonna have music on these records that’s gonna be gold!”

In 1949 Shuler stumbled on local success when he offered to record a Cajun accordionist Ira “Iry” Lejeune on his new Folk-Star label. Lejeune and Shuler bribed the KAOK radio station operator with a pint of whiskey to use the station at night to record Lejeune’s band. The demand for Lejeune’s 78 RPM recordings in jukeboxes surprised Shuler, forcing him to reconsider his own career as a musician. Instead he felt there was more money to be made as an independent record producer and distributor.

A Wave of Success

By 1954 Shuler was entertaining local and remote talent from East Texas to the Atchafalaya swamp. He accepted the opportunity to have virtually unknown accordionist Wilson Anthony “Boozoo” Chavis front a local R&B band in his studio, and together, they recorded Boozoo’s signature song, “Paper In My Shoe.” Unbeknownst to Shuler at the time, Shuler’s mixture of R&B with a diatonic accordion helped craft the earliest recordings of what would later be widely recognized as a new genre—zydeco.

After Lejeune’s death in 1955, Shuler turned to other local Cajun and zydeco artists to help fill his music catalog. Southwest Louisiana musicians like Clarence Garlow, Sidney Brown, and Leroy Broussard took turns laying down tracks at Shuler’s Lake Charles studio. Shuler continued using his Goldband and Folk-Star labels back-to-back to appeal to the broader South Louisiana music market. With the advent of the new 45 RPM format, releasing and distributing records became even easier.

As rock and roll and Nashville-based country music took the world by storm, independent Louisiana record producers like Shuler began steering their efforts away from folk talent and toward the popular trends of the time. The Goldband studio saw the likes of the Boogie Ramblers, Hop Wilson, Bee Arnold, Al Ferrier, Gene Terry, Guitar Jr., and a thirteen-year-old country music singer named Dolly Parton. In 1959 Parton and her uncle traveled more than thirty hours to reach the studio, where Shuler recorded her singing her first single, “Puppy Love.” That same year a local bellhop named John Philip Baptiste, better known as Phil Phillips, wrote and recorded Shuler’s first hit single “Sea of Love”—a song that reached No. 1 on Billboard R&B Singles and No. 2 on the Billboard Hot 100 respectively. With the help of Lake Charles record store owner George Khoury, the song was eventually licensed to Mercury Records, where it sold more than a million copies.

End of an Era

In some ways Shuler’s business practices were ahead of his time. He was one of the first Louisiana music producers to embrace vinyl reissues, distributing to both the jukebox market as well as the commercial market. He released several versions of Iry’s master recordings on different labels, with different colors, even touting some as “collector’s items.” In other cases he was quick to modernize and alter the sound. When Chris Strachwitz of Arhoolie Records commented that Shuler’s recordings “lacked bottom,” noting an apparent absence of low-end frequencies, Shuler immediately had local artists overdub bass tracks before transferring his master tapes to the new vinyl LP format.

However, Shuler’s dealings were not without controversy. Outside his business acumen, Shuler was known to be crafty—even devious. Stories abound of Goldband artists attempting to collect their share of royalties, only to discover Shuler’s name listed alongside theirs in the song’s writing credits—allowing him to receive up to half of the song’s profits.

The late 1960s saw a folk revival in traditional Cajun music across the country with an increasing Cajun music repertoire in folk festival itineraries. Shuler began using his Goldband label to bring legacy artists to modern notoriety, such as the Hackberry Ramblers and J. B. Fuselier, as well as emerging local Cajun artists like Cleveland Crochet, Joe Bonsall, Shorty Leblanc, and Jo-El Sonnier, a Cajun-country music star who would break through country music’s Top 10 list twice.

Throughout the 1970s Shuler’s success with Goldband Records waned. Relatively unknown talent like Mickey Gilley, Freddie Fender, and Katie Webster graced the studio, but as the decade progressed, music tastes and the recording business changed. The Goldband label and the activity in the studio began to fade after the 1980s, but Shuler continued to operate the business as a record store until he passed away on July 23, 2005.

Today the Southern Folklife Collection at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill maintains the Goldband Recording Corporation Collection archive.