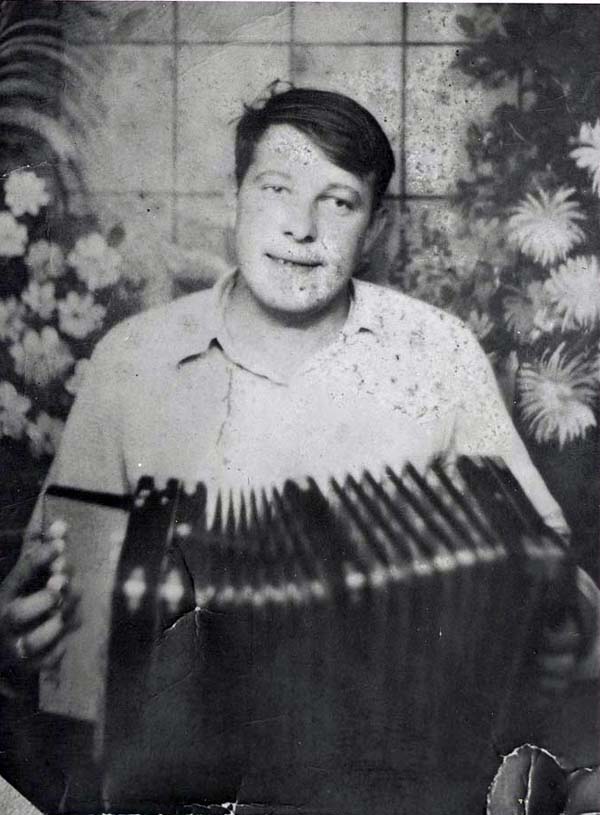

Iry LeJeune

At a time when popular Cajun music leaned heavily toward western swing bands featuring the fiddle, Iry LeJeune is credited with reintroducing the traditional Cajun accordion.

Courtesy of University of North Carolina Chapel Hill

Iry LeJeune. Unidentified

Accordionist, vocalist, and composer Iry LeJeune was an expert musician who helped ensure the continuation of early twentieth-century Cajun musical traditions after World War II. A popular recording artist in his own time, LeJeune helped restore the role of accordion-led music ensembles within Cajun music during a period when string bands heavily influenced by commercial western swing dominated the Cajun musical marketplace. Since his untimely death in an auto accident three weeks short of his twenty-seventh birthday in 1955, musicians and historians have come to admire LeJeune’s achievements as a musical and cultural pioneer. As Louisiana historian Ann Savoy explains, Iry LeJeune stands out for “his intense originality combined outstanding technical mastery … [He] showed his fellow Cajuns that a man could be himself in the face of the Americanization process: he could wear his old clothes, he could speak his own French, and he could let out his deepest emotions. He could, in fact, be a Cajun and still be important.”

Immersed in Rural Cajun Musical Traditions

Born legally blind in an isolated farming community in the Cajun prairies northwest of Lafayette, the youngster grew up within a musical family, with a father and two uncles who would prove essential in his musical evolution. His father, Agnus LeJeune, was a tenant farmer and an accomplished Cajun fiddler, while uncles Angelas LeJeune and Steven LeJeune had both played professionally. Angelas, in fact, recorded in New Orleans for the Brunswick label and was a friend of Amédé Ardoin, an African-American accordionist known as a founding father of accordion playing in both Cajun and Creole music. In his teens, Iry LeJeune spent long days at his uncle’s house, playing the accordion and listening to his uncle’s collection of Amédé Ardoin recordings. As he grew older, on Saturday mornings—with his own instrument given to him by his uncle Steven—Iry would wrap his accordion in a burlap sack, walk to the nearest main road, and hitchhike to anywhere he could find a live audience.

Leading a Post-World War II Cajun Musical Revival

LeJeune eventually relocated to the Lake Charles region, where he found a thriving music scene among the many dance halls. In Lake Charles, LeJeune met fiddler Floyd LeBlanc, who convinced the young accordionist to accompany him to Houston, Texas, where Lejeune made his first recordings, “Love Bridge Waltz” and “Evangeline Special.” Noting the rise in celebrity and increased attendance at dance halls these recordings brought him, LeJeune returned to Lake Charles six months later and convinced disc jockey Eddie Shuler to record his music. With very little record-making expertise, Shuler recorded Iry LeJeune. In the process, Shuler founded Goldband records, which became a regional success in the 1950s and early 1960s. LeJeune, meanwhile, fell into a regular routine. He played the regional dance halls and, whenever attendance began to drop, released new records, thus providing enough income to support himself, his band, his wife, and five children. In an era when string bands were most prominent, LeJeune played old-time Cajun music in an accordion-led band. In so doing, he opened the door for handfuls of soon-to-be-prominent contemporaries who also played in an older style, including Lawrence Walker, Aldus Roger, and Nathan Abshire.

A Reputation Obscured by Changing Musical Tastes

Just after midnight on Sunday, October 8, 1955, LeJeune and fiddler J. B Fuselier pulled over to the side of a state highway to change a spare tire on their way home from a performance in Eunice. A speeding car struck both men; Fuselier suffered a broken leg and collarbone, and LeJeune died at the scene. LeJeune’s reputation was obscured by the continuing careers of his contemporaries and successors, as well as changing musical tastes. The later resurgence of LeJeune’s reputation reflects a broader musical evolution, including a growing nationwide interest in grassroots styles and regional sources of American “folk” music. More specifically, LeJeune figures heavily in the Cajun music revival that began in the 1970s with celebrated older musicians like Dewey Balfa and Dennis McGee, now heroicized by a younger generation interested in preserving traditional Cajun music.

From Tragic Folk Hero to Cajun Virtuoso

Iry LeJeune’s reputation lingers despite the brevity of his career and his relatively small archive of just twenty-five recorded songs. His rural upbringing, largely undocumented career, and untimely death make him a sometimes-idealized and tragic folk hero: the blind musician raised in rural isolation who died young and, as Cajun-music historian John Broven puts it, “whose primitive sounds belonged to another era.”

In 2009, the National Recording Registry at the Library of Congress cited LeJeune for inclusion with this fitting summary of his contributions: “The post-World War II revival of traditional Cajun music began with accordionist Iry LeJeune’s first single, his influential recordings of ‘Evangeline Special’ and ‘Love Bridge Waltz’ … [His] emotional and deeply personal style was immensely popular with Louisiana Cajuns returning home from the war, eager to hear their own music again .… He is [now] regarded as one of the best Cajun accordionists and singers of all time.”