Hank Williams Jr.

Hank Williams Jr. is an accomplished country-music star and defiant idealogue.

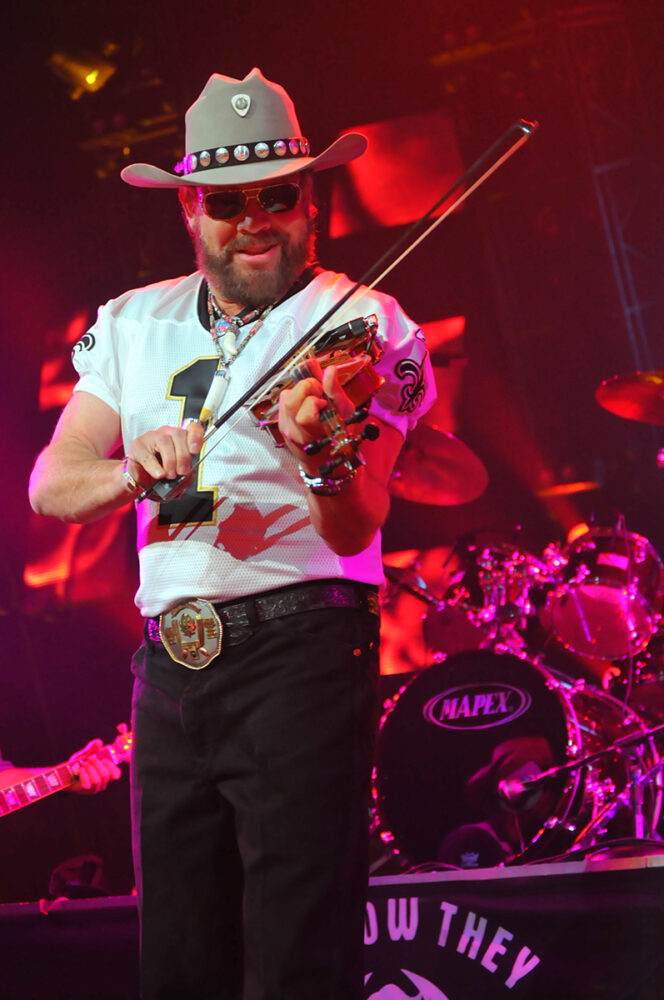

Wikimedia Commons

Country musician Hank Williams Jr. playing fiddle on stage in April 2008. Adambroachphotography, photographer.

Hank Williams Jr. is a prolific songwriter, vocalist, multi-instrumentalist, and popular chart-topping performer whose career dates back to the mid-1950s. While best known as a country musician, Williams’s work also intersects with the related genres of Southern rock and blues. In addition, Williams draws considerable media attention as a vociferous contrarian with a penchant for political controversy.

Randall Hank Williams was born in Shreveport, in Caddo Parish, on May 26, 1949. At that time his father, Hank Williams—a budding top-tier country star—was based in Shreveport, where he performed weekly on the Louisiana Hayride. This popular live-performance radio program helped launch the national-level careers of Williams and subsequent country/rockabilly luminaries, including Johnny Cash and Elvis Presley, among many others. In 1949 Hank Williams Sr. moved to Nashville and became a member of the Grand Ole Opry, the nation’s top country music live radio broadcast. Williams’s career soared until his untimely death in 1953. Bereaved adoring fans expected Hank Jr. to carry the torch of his father’s music, which he did with enthusiasm. At the age of eight, he began performing on the Audrey Williams Musical Caravan of Stars, produced by his mother. These events found Williams billed alongside adults such as the rockabilly pioneer Carl Perkins and the comedic rocker J. P. Richardson Jr., known as the Big Bopper.

Williams appeared on the Grand Ole Opry in 1960 and recorded his first album in 1963. During the next decade he had eleven top-forty country hits in the course of releasing twenty-one albums, including a greatest hits compilation. One such hit was “Cajun Baby,” a romanticized depiction of South Louisiana in a style similar to his father’s hit “Jambalaya (On the Bayou).” Hank Williams Jr.’s popularity was further enhanced by national television appearances on the popular variety shows hosted by Ed Sullivan and Jimmy Dean, and on the rock-oriented program Shindig.

Upon reaching his early twenties Williams yearned to grow artistically. In an interview posted as a Facebook reel by the Instagram account “cornbreadcountryclub” (original interviewer unknown), Williams stated that, as a young man, “All I ever thought about was going out and imitating Daddy, doing his songs like I was trained to do. I had all the money I could spend, I was a little rich boy… but then I got serious in the early ‘70s, when the little boy became a young man, and I decided I wasn’t going to go out and imitate Daddy anymore.” In the documentary Living Proof: The Hank Williams Jr. Story, Williams said, “If I could make an album that showed the connection between country and the new rock, then I could look at myself in the mirror in the morning. I’d be making my music, not Daddy’s, or Mother’s, or anybody else’s.” Toward this goal, the mid-‘70s found Williams collaborating with leading musicians in the Southern rock field, as heard on the albums Hank Williams, Jr. & Friends, and The New South. (The ‘70s term “Southern rock,” as personified by the Allman Brothers Band, was redundant in the sense that a great deal of rock music originated in the South, but this fact was not widely acknowledged until the ‘70s, after which the descriptor Southern Rock quickly faded from common parlance, except as a point of historical reference.)

The late ‘70s saw Hank Williams Jr. record a series of emotionally powerful, soulful original songs that established him as a substantial musical talent in his own right. These included “Whiskey Bent and Hell Bound,” “A Country Boy Can Survive,” and, most notably, “Family Tradition,” which referenced his father: “I am very proud of my daddy’s name, even though his kind of music and mine ain’t exactly the same.” The instrumental accompaniment on these hits combined a mid-century country-music sensibility with a loud, aggressive rock edge.

These years of great success for Williams were affected by substance abuse issues, due in part to a reliance on pain medications following a near-fatal accident. Notorious recordings of a seemingly intoxicated Williams circulated on cassette tapes in music-business circles and can now be heard online. Nevertheless, Williams’s prodigious career and record sales proceeded in high gear; between 1979 and 1992 he released twenty-one albums—eighteen studio recordings and three reissue compilations—that were all certified, at minimum, at the gold record level (five hundred thousand copies sold) or platinum (a million copies sold), by the Recording Industry Association of America. In terms of singles, between 1979 and 1990, thirty of Williams’s songs reached the top ten on the Billboard magazine country music charts, including eight that went to number one.

In 1988 Williams’s song, “If the South Would’ve Won”—referring to the Civil War—espoused his controversial political views. The following year, another Williams original, “All My Rowdy Friends Are Coming Over Tonight,” became the theme song for ESPN’s Monday Night Football, but in 2011 ESPN dropped the song when, speaking on the Fox television network, Williams equated Barack Obama with Adolf Hitler. The following year Williams publicly stated that Obama was a Muslim. In 2017, however, ESPN welcomed Williams’s return to Monday night football, opining that “it was just the right time to bring him back.” A year later Williams’s song “Take A Knee, Take A Hike” excoriated football players such as Colin Kaepernick for kneeling during the playing of the national anthem at NFL games in protest against police brutality and racial inequality.

In 2022 Williams recorded the provocatively entitled album Rich White Honky Blues, which featured his renditions of popular favorites from this bedrock African American genre and began a lengthy tour to promote the album. Throughout his six-decade career, Hank Williams Jr. has often performed in Louisiana.